2024 Reports 5 to 7 of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 5—Professional Services Contracts

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and Recommendations

- Contracting weaknesses were common across departments, agencies, and Crown corporations

- Organizations did not consistently follow procurement policies when awarding contracts

- Departments and agencies tailored some procurement processes to suit the contractor

- Not all competitive contracts awarded in a transparent manner

- Frequent lack of justification for awarding non‑competitive contracts

- Weak justification for chain of non‑competitive contracts after initial contract

- Opportunities to improve conflict‑of‑interest procedures

- Lack of enforcement of security requirements

- Organizations’ contracting practices often did not promote value for money

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Exhibits

- 5.1—Departments, agencies, and Crown corporations awarded 97 contracts to McKinsey & Company from 1 January 2011 to 7 February 2023

- 5.2—Spending by departments and agencies on contracts awarded to all professional service providers

- 5.3—Spending by departments and agencies and spending by departments, agencies, and Crown corporations on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company

- 5.4—Several organizations awarded chains of non‑competitive contracts

Introduction

Background

5.1 The Government of Canada requires a broad range of professional services to operate. These services include

- technical, scientific, or professional expert assistance and advice (for example, lawyers, architects, engineers, medical personnel, and management, audit, financial, or business consultants)

- health care, welfare, and training services

- operational and maintenance services (for example, building cleaning services or temporary help)

5.2 Departments, agencies, and Crown corporations may supplement internal capacity when needed to achieve their goals. Some examples include contracting for services to temporarily expand capacity to complete a high volume of work in a timely manner or to obtain a specialized skill set that is not available internally or would not be cost effective to maintain on a permanent basis. Federal organizations are to make contracting decisions with a view to being respectful stewards of resources, ensuring value for money is obtained.

5.3 When departments and agencies seek professional services for a particular activity or initiative, they may procure services through competition, negotiate the terms of each contract directly with suppliers, or procure such services through established standing offer agreementsFootnote 1 and supply arrangements,Footnote 2 which may be competitive or non‑competitive. Crown corporations may have similar arrangements with contractors.

5.4 The decision to initiate contracts with professional services firms rests with the deputy heads of individual departments and agencies and the heads of Crown corporations, who are responsible for their organization’s resourcing decisions. For departments and agencies, the rules and procedures for contracting are set by the Government Contracts Regulations, by policies issued by the Treasury Board, and by trade agreements. Crown corporations are not subject to these regulations and policies but in general are subject to the trade agreements. Crown corporations develop and implement their own procurement policies, which differ among Crown corporations and may not align with Treasury Board procurement policies.

5.5 On 7 February 2023, the House of Commons unanimously passed a motion to concur with the January 2023 request by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates that the Auditor General of Canada conduct a performance and value‑for‑money audit of the contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company since 1 January 2011 by any department, agency, or Crown corporation. Our audit is the first public examination of contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company by Crown corporations.

5.6 McKinsey & Company is a global professional services firm serving clients in the private and public sectors. During the audit period, McKinsey & Company was awarded contracts by federal organizations for benchmarking, management consulting, and information technology (IT) consulting.

5.7 Internal audits at departments and agencies. The Office of the Comptroller General, within the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, directed the chief audit executives of departments and agencies that had contracts with McKinsey & Company from 1 January 2011 to 7 February 2023 to conduct independent internal audits of the procurement processes associated with these contracts. At a minimum, chief audit executives had to cover all areas of the audit plan and audit program developed by the Office of the Comptroller General. The results were provided to the Comptroller General of Canada by 22 March 2023 and were released publicly on 30 March 2023. This work focused on compliance with procurement policies and processes. The internal audit work did not assess value for money.

5.8 Internal reviews at Crown corporations. Crown corporations are not subject to Treasury Board procurement and internal audit policies. They were therefore not included in the Office of the Comptroller General’s review. Instead, in February 2023, the President of the Treasury Board requested that ministers who were responsible for Crown corporations communicate information to the heads of Crown corporations to encourage them to undertake, in the same spirit, reviews of contracts issued to McKinsey & Company. Crown corporations could decide whether to undertake reviews, and 5 of the 10 Crown corporations that had contracts with McKinsey & Company did so.

5.9 Office of the Procurement Ombud review. The Minister of Public Services and Procurement requested that the Office of the Procurement Ombud review the procurement practices that federal departments and agencies used to acquire services through contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company. This review was made public on 15 April 2024. The Office of the Procurement Ombud does not have the authority to review procurement practices of Crown corporations.

5.10 The several audits and reviews requested by the Comptroller General of Canada, the President of the Treasury Board, and the Minister of Public Services and Procurement between March 2023 and March 2024 found numerous administrative and procedural weaknesses in the management of procurements. These included, for example, failing to obtain a signed contract before work began or failing to maintain relevant contracting documents on file. While these weaknesses did not affect the decision to issue a contract to McKinsey & Company or increase risks to achieving value for money, which are the focus of this report, they demonstrated weaknesses in administering the procurement process.

5.11 Recommendations. Each of the reviews contained many recommendations to, and action plans by, the organizations included in the scope of our audit. As well as calling on central agencies to improve their guidance on expected contracting practices, the recommendations had several themes, namely that all federal organizations should

- comply with procurement rules

- document their procurement decisions

- improve quality control over their procurement practices

5.12 We made a single recommendation in the area of conflicts of interest that we believe was not addressed by previous recommendations. Where our audit confirmed the gaps identified in those reviews, rather than repeat recommendations or recommend that organizations follow existing rules, we encourage departments, agencies, and Crown corporations to implement the recommendations resulting from those audits and reviews. We recognize that some procurement policies and approaches have since changed. We did not examine these changes, as they did not affect the awarding of the contracts we audited.

5.13 Since not all Crown corporations conducted internal audits or reviews and were not subject to review by the Office of the Procurement Ombud, we encourage Crown corporations to examine the recommendations in these various reports and our findings in this report to identify opportunities to strengthen their policies and procedures for awarding and managing professional services contracts.

5.14 This audit includes 20 of the 21 departments, agencies, and Crown corporations that reported they had contracts with McKinsey & Company from 1 January 2011 to 7 February 2023.

5.15 One Crown corporation, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, was not included in the audit. The corporation’s legislative framework, and particularly its joint federal–provincial governance structure, is different from the legislative frameworks of other Crown corporations, and the corporation is therefore not subject to audit by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. We do not know how many contracts the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board awarded to McKinsey & Company during the period covered by the audit or the total value of those contracts.

5.16 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. The secretariat provides advice and makes recommendations to the Treasury Board committee of ministers on how the government spends money on programs and services. The secretariat also provides advice and recommendations on how the government regulates and is managed. This includes establishing procurement directives and guidance for departments and agencies.

5.17 Public Services and Procurement Canada. This department supports the Government of Canada by being its central purchasing and contracting authority. The department is responsible for issuing and administering contracts on behalf of departments and agencies when the contract value exceeds certain delegated procurement authorities. It is also responsible for issuing standing offers and supply arrangements that can be used by all departments and agencies. Although Crown corporations are not required to use procurement vehicles of the department, they may access these services. These procurement vehicles are intended to save time and money in the supply of goods and services.

5.18 Departments and agencies. According to Treasury Board policies and directives, departments and agencies are responsible for demonstrating sound stewardship and best value in their procurement actions and decisions. Actions related to procurement management are also expected to be fair, open, and transparent and to meet public expectations in matters of prudence and probity. Departments and agencies are expected to establish effective governance and oversight mechanisms to achieve this. At the time of our audit, the 2021 Treasury Board Policy on the Planning and Management of Investments and its associated Directive on the Management of Procurement establish these responsibilities.

5.19 Departments and agencies are also responsible for meeting the requirements of the Government Contracts Regulations and trade agreements, such as those related to competitive and non‑competitive contracting. Under these provisions, contracting authorities may enter into a contract without soliciting bids under specific conditions, which is a non‑competitive procurement process.

5.20 Crown corporations. Each corporation is responsible for developing and implementing its own procurement policies and procedures. In general, Crown corporations are subject to Part X of the Financial Administration Act, and, like departments and agencies, in general, they are subject to trade agreements. Crown corporations have a responsibility for carrying out their operations effectively and efficiently and are responsible for safeguarding their resources.

Focus of the audit

5.21 This audit focused on whether professional services contracts were awarded to McKinsey & Company in accordance with applicable procurement policies and whether the federal public sector obtained value for money.

5.22 This audit is important because the federal public sector spends billions of dollars of public funds on contracting each year. The audit provides assurance to Canadians about whether the controls, processes, and policies in place support fair, open, and transparent procurements and promote value for money.

5.23 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and Recommendation

Contracting weaknesses were common across departments, agencies, and Crown corporations

5.24 This finding matters because following procedures increases the probability that needed services will be delivered effectively while providing value for money.

Frequent disregard for policies and for managing risks to value for money

5.25 We found that the 20 federal departments, agencies, and Crown corporations included in this audit awarded McKinsey & Company 97 contracts with a total value of approximately $208.7 million before taxes over a period of 12 years from 1 January 2011 to 7 February 2023 (Exhibit 5.1).

Exhibit 5.1—Departments, agencies, and Crown corporations awarded 97 contracts to McKinsey & Company from 1 January 2011 to 7 February 2023

Departments and agencies

| Organization | Value of awarded contracts (before taxes) | Total amount spent (before taxes) as of 30 September 2023 | Total number of contracts | Number of competitive contracts | Number of non‑competitive contracts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Canada Border Services Agency |

$6,256,671 |

$4,337,610 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

|

Employment and Social Development Canada |

$5,775,290 |

$5,775,290 |

4 |

0 |

4 |

|

Department of Finance Canada |

$657,522 |

$642,431 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada |

$24,548,250 |

$24,536,693 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

|

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada |

$3,398,670 |

$3,398,670 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

|

National Defence |

$25,799,500 |

$23,637,000 |

15 |

2 |

13 |

|

Natural Resources Canada |

$797,000 |

$797,000 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Privy Council Office |

$21,900 |

$21,900 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Public Services and Procurement Canada |

$26,234,625 |

$26,234,625 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

|

Veterans Affairs Canada |

$22,000 |

$22,000 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

$93,511,428 |

$89,403,219 |

36 |

13 |

23 |

Crown corporations

| Organization | Value of awarded contracts (before taxes) | Total amount spent (before taxes) as of 30 September 2023 | Total number of contracts | Number of competitive contracts | Number of non‑competitive contracts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Atomic Energy of Canada Limited |

$540,000 |

$540,000 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Bank of Canada |

$150,000 |

$150,000 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Business Development Bank of Canada |

$21,838,000 |

$20,960,701 |

11 |

5 |

6 |

|

Canada Development Investment Corporation |

$1,350,000 |

$1,350,000 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

Canada Infrastructure Bank |

$1,720,000 |

$1,430,000 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

Canada Post |

$26,630,813 |

$26,630,813 |

14 |

5 |

9 |

|

Destination Canada |

$2,795,000 |

$2,795,000 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

Export Development Canada |

$12,366,761 |

$12,326,000 |

10 |

1 |

9 |

|

Public Sector Pension Investment Board |

$14,908,520 |

$12,484,183 |

18 |

0 |

18 |

|

Trans Mountain Corporation |

$32,900,000 |

$32,213,000 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

$115,199,094 |

$110,879,697 |

61 |

15 |

46 |

|

Total |

$208,710,522 |

$200,282,916 |

97 |

28 |

69 |

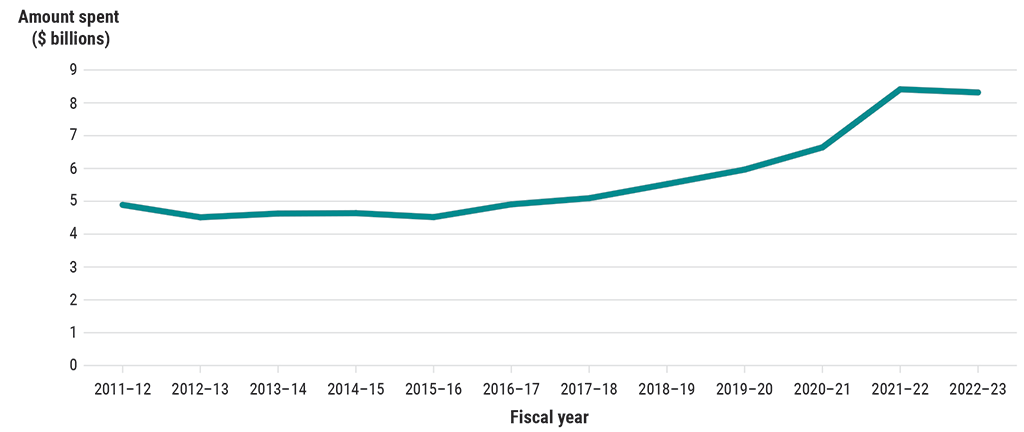

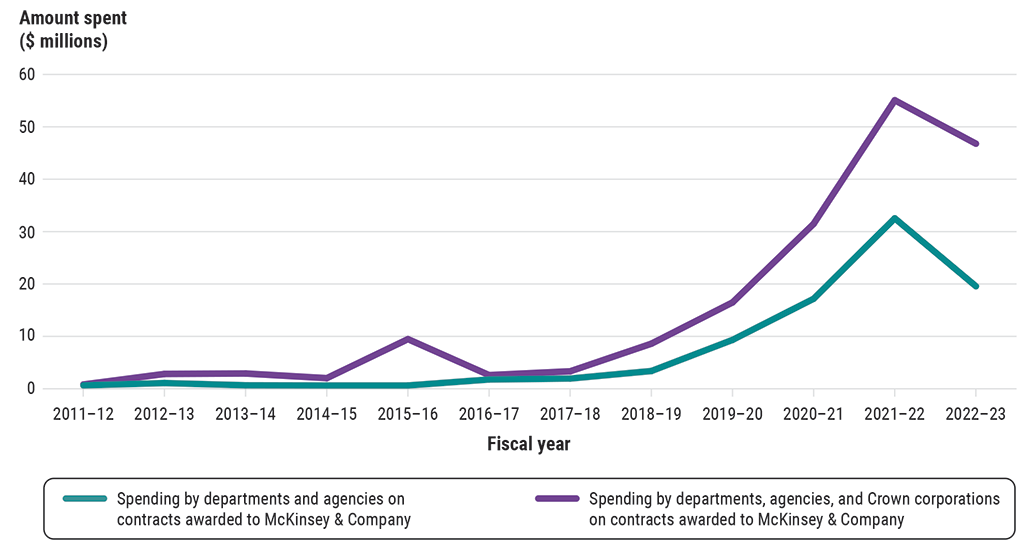

5.26 The Public Accounts of Canada reports details of the amount spent on contracts by category of professional services by departments and agencies but not Crown corporations. The categories for which contracts were awarded to McKinsey & Company were health and welfare services, informatics services, management consulting, scientific and research services, temporary help services, and other services. We found that the amounts paid to McKinsey & Company from 1 April 2011 to 31 March 2023 were 0.27% of the amount paid to all service providers for these categories. We also found that the amount paid for these professional services categories increased from 2015 (Exhibit 5.2). From the 2017–18 fiscal year, the amounts paid to McKinsey & Company by departments, agencies, and Crown corporations increased (Exhibit 5.3).

Exhibit 5.2—Spending by departments and agencies on contracts awarded to all professional service providersNote *

Source: Public Accounts of Canada information, which includes only departments and agencies. It does not include Crown corporations.

Exhibit 5.2—text version

This exhibit shows the spending in billions of dollars by departments and agencies on contracts awarded to all professional service providers for 12 fiscal years from 2011–12 to 2022–23. The data comprises only categories that included contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company: health and welfare services, informatics services, management consulting, scientific and research services, temporary help services, and other services.

Overall, spending was steady at about 4.6 billion dollars from the 2011–12 fiscal year until the 2015–16 fiscal year, when spending started to increase. It reached 8.4 billion dollars in the 2021–22 fiscal year and then decreased to 8.3 billion dollars in 2022–23.

- In the 2011–12 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $4,891,249,690 on professional services contracts.

- In the 2012–13 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $4,513,735,896 on professional services contracts.

- In the 2013–14 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $4,627,925,618 on professional services contracts.

- In the 2014–15 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $4,639,706,616 on professional services contracts.

- In the 2015–16 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $4,518,955,624 on professional services contracts.

- In the 2016–17 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $4,909,160,856 on professional services contracts.

- In the 2017–18 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $5,094,232,989 on professional services contracts.

- In the 2018–19 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $5,525,569,877 on professional services contracts.

- In the 2019–20 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $5,966,705,116 on professional services contracts.

- In the 2020–21 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $6,643,298,128 on professional services contracts.

- In the 2021–22 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $8,411,135,985 on professional services contracts.

- In the 2022–23 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $8,316,502,952 on professional services contracts.

Exhibit 5.3—Spending by departments and agencies and spending by departments, agencies, and Crown corporations on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company

Source: Public Accounts of Canada information for spending by departments and agencies and our office for spending by Crown corporations

Exhibit 5.3—text version

This exhibit compares the spending in millions of dollars on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company for 12 fiscal years from the 2011–12 fiscal year to the 2022–23 fiscal year. The comparison is of spending by departments and agencies with spending by departments, agencies, and Crown corporations.

Overall, the spending by departments and agencies and by departments, agencies, and Crown corporations increased from the 2017–18 fiscal year to the 2022–23 fiscal year, with the highest amounts spent in the 2021–22 fiscal year. The spending by departments and agencies increased from 642 thousand dollars in the 2011–12 fiscal year to a high of 32.5 million dollars in the 2021–22 fiscal year and then decreased to 19.6 million dollars in the 2022–23 fiscal year. In comparison, the spending by departments, agencies, and Crown corporations increased from 817 thousand dollars in the 2011–12 fiscal year to a high of 55.1 million dollars in the 2021–22 fiscal year and then decreased to about 46.8 million in the 2022–23 fiscal year.

Spending by departments and agencies per fiscal year:

- In the 2011–12 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $642,431 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2012–13 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $1,093,584 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2013–14 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $500,000 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2014–15 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent no money on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2015–16 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent no money on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2016–17 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $1,769,910 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2017–18 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $1,953,000 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2018–19 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $3,389,700 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2019–20 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $9,327,880 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2020–21 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $17,184,670 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2021–22 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $32,534,706 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2022–23 fiscal year, departments and agencies spent $19,569,875 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

Spending by departments, agencies, and Crown corporations per fiscal year:

- In the 2011–12 fiscal year, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations spent $817,431 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2012–13 fiscal year, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations spent $2,831,940 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2013–14 fiscal year, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations spent $2,912,972 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2014–15 fiscal year, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations spent $2,028,968 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2015–16 fiscal year, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations spent $9,476,420 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2016–17 fiscal year, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations spent $2,604,757 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2017–18 fiscal year, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations spent $3,338,000 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2018–19 fiscal year, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations spent $8,604,933 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2019–20 fiscal year, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations spent $16,479,772 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2020–21 fiscal year, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations spent $31,485,962 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2021–22 fiscal year, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations spent $55,069,526 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

- In the 2022–23 fiscal year, departments, agencies, and Crown corporations spent $46,779,382 on contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company.

5.27 Out of a total of 97 contracts awarded, we were able to complete our audit work on procurement compliance on 92 of those contracts. For the other 5, documents were no longer available because of information-retention policies. We used representative sampling to examine whether 33 contracts provided value for money: 14 contracts awarded by departments and agencies and 19 contracts awarded by Crown corporations (see About the Audit).

5.28 As the following sections explain in detail, we found frequent disregard for procurement policies and guidance and risks to value for money across the contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company both by departments and agencies and by Crown corporations. The extent of non‑compliance and risks to value for money varied considerably across federal organizations. However, 9 out of 10 departments and agencies and 8 out of 10 Crown corporations failed to properly follow all aspects of their procurement policies and guidance on at least 1 contract. For our sample of 33 contracts, we found in 19 (58%) cases, 1 or more of the following elements were not clear:

- that there was a need for the contract

- what the expected deliverables were

- whether all the deliverables were provided

- that the ultimate intent of the contract was achieved

All of the above meant that value for money could not be demonstrated for these contracts. In addition, 11 of these 19 contracts had 2 or more of these problems. As well, for 30 contracts, the cost was not estimated in advance, representing a risk to obtaining value for money.

Organizations did not consistently follow procurement policies when awarding contracts

5.29 This finding matters because procurement policies are intended to ensure that contracts are awarded in a manner that demonstrates fairness, openness, transparency, sound stewardship, and value for money.

Departments and agencies tailored some procurement processes to suit the contractor

5.30 We found that 28 (29%) of the 97 contracts with McKinsey & Company (Exhibit 5.1) were awarded through a competitive process, which represented a total maximum contract value of $91 million. Of the 28 competitive contracts

- 13 were awarded by departments and agencies

- 15 were awarded by Crown corporations

5.31 We found that in 4 out of the 28 contracts awarded through a competitive process, procurement strategies were structured to make it easier for McKinsey & Company to be awarded the contracts:

- For 2 of the 4 contracts, the Canada Border Services Agency and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada modified their procurement strategy once informed that McKinsey & Company was not a pre‑qualified vendor under the supply arrangement originally considered. As a result, the department and the agency modified the contract requirements to be able to use a different supply arrangement. We did not see other documentation that would support the change in approach.

- For the 2 other contracts, McKinsey & Company was the only service provider to submit a bid. Other potential bidders raised concerns that the criteria were overly restrictive. We found no evidence in files maintained by the Canada Border Services Agency to support the rationale of not addressing bidders’ concerns. We also found that Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada responded to bidders’ questions; however, in some instances, the department did not document its rationale for not making changes to address bidders’ concerns.

5.32 In addition, we found that National Defence and Employment and Social Development Canada waited more than a year for a non‑competitive national master standing offer to be created with McKinsey & Company. Each was seeking benchmarking services that may have been available under other national master standing offers. It is unclear why the organizations chose to wait rather than using another procurement option.

5.33 The 6 contracts above were awarded for a total maximum value of $27.2 million before taxes.

Not all competitive contracts awarded in a transparent manner

5.34 For 10 of the 28 contracts that were awarded through a competitive process, we found the documentation about the bid evaluations was not sufficient to support the selection of McKinsey & Company as the winning bidder. These 10 contracts represented a total maximum contract value of $13.7 million before taxes. The documentation gaps were as follows:

- One contract was awarded by the Business Development Bank of Canada when, according to the evaluation completed, it was not the highest scoring bid. While the organization was not required to select the highest scoring bid, no explanation was documented to support why McKinsey & Company was selected when the quoted price was considerably higher than others.

- For 2 contracts awarded by the Canada Infrastructure Bank, no evaluation criteria were included in the request for bids or used in the evaluation of bids. No explanation was documented to support why McKinsey & Company was selected.

- For 1 contract with the Canada Development Investment Corporation, evaluation criteria were identified in the request for proposal stage, but no scores were assigned for each of the criteria at the evaluation stage when determining the winning bidder.

- In 6 other contracts, 1 from the Business Development Bank of Canada, 3 from the Canada Border Services Agency, and 2 from Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, bid evaluation documents were incomplete or not on file.

5.35 Without documentation supporting the selection of the winning bidder, how the evaluation criteria were used, or why the results of a procurement process were not consistent with the evaluation criteria, it is not possible to conclude that the organizations’ decisions in awarding the contracts to McKinsey & Company were sound business decisions or ones that provided value for money.

5.36 The contract issued by the Canada Development Investment Corporation followed an urgent request by the Department of Finance Canada to help secure external advice. Although the role of the corporation includes advising on the government’s commercial interests, in this case we found that the approach adopted by the Department of Finance Canada limited competition and transparency for a contract with a value of $1.35 million. The Department of Finance Canada provided the statement of work, and senior officials from the department and the Crown corporation were involved in the bid evaluation process. The Crown corporation issued the contract after inviting 3 firms to bid on the work, as permitted by its contracting policy. In our view, the department’s approach raises the perception that it used the Crown corporation as a proxy to avoid the public service’s competitive procurement requirements.

Frequent lack of justification for awarding non‑competitive contracts

5.37 We found that 69 (71%) of 97 contracts to McKinsey & Company were awarded as non‑competitive contracts, which represented a total maximum contract value of $117.7 million. Of the 69 non‑competitive contracts

- 23 were awarded by departments and agencies

- 46 were awarded by Crown corporations

5.38 For a non‑competitive contract to be awarded by a department or agency

- an exception permitted under the Government Contracts Regulations and trade agreements must be fully justified

- the justification should be included in the procurement file

5.39 Public Services and Procurement Canada established a national master standing offer in 2021 with McKinsey & Company through a non‑competitive process. We found that when the national master standing offer was established, Public Services and Procurement Canada’s justification for a non‑competitive standing offer was weak and did not demonstrate that McKinsey & Company would provide a unique service.

5.40 A total of 19 non‑competitive contracts (16 contracts by 3 departments and agencies and 3 contracts by 2 Crown corporations) were issued using this same standing offer. These 19 contracts were awarded from February 2021 to February 2023, with a total maximum contract value of $42.4 million. A call‑up against a standing offer establishes a contract. All contracts are subject to the requirements to justify and document support for a non‑competitive procurement strategy. For 18 of the 19 contracts issued under the national master standing offer, the organizations did not document justifications for the non‑competitive procurements, and Public Services and Procurement Canada did not require justifications prior to issuing the contracts.

5.41 Departments and agencies properly documented the remaining 7 of their 23 non‑competitive contracts as exceptions, under the Government Contracts Regulations.

5.42 Of the 46 non‑competitive contracts issued by Crown corporations, 11 contracts issued by the Public Sector Pension Investment Board did not have to be competed under its procurement policy for certain types of contracts. In addition, for 3 contracts issued by the Public Sector Pension Investment Board, we could not review documentation supporting the procurement process. The documentation had been destroyed because the contract award date fell outside the time frame in the Crown corporation’s document retention policy.

5.43 For the 32 contracts that required a non‑competitive justification to meet the requirements of the Crown corporation’s policy, we found that 13 justifications lacked rigour and 10 more were not documented. For example:

- The Business Development Bank of Canada awarded 2 contracts through non‑competitive processes without documenting justifications, as required by its directive. For 4 more contracts, the justifications were not documented at the time the contracts were awarded.

- The Trans Mountain Corporation issued a non‑competitive contract in October 2022 without a justification clearly linked to one of the exceptions to competitive procurements contained in its policy.

Weak justification for chain of non‑competitive contracts after initial contract

5.44 In our representative sample of 33 contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company, we found 4 series of contracts (chains) where, after awarding an initial contract with no competition, organizations then awarded additional non‑competitive contracts for continuous or related work. For 4 other chains, only the initial contract was awarded competitively. The total number of contracts involved in these chains of contracts, including those outside of our sample, was 30, for a total amount awarded of approximately $58 million (Exhibit 5.4).

Exhibit 5.4—Several organizations awarded chains of non‑competitive contracts

Departments and agencies

| Organization | Value of original competitive contract (before taxes) | Value of original non‑competitive contract (before taxes) | Approximate total value of chain of contracts (before taxes) | Number of non‑competitive contracts following the initial contract | Time period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Employment and Social Development Canada |

Not applicable |

$35,000 |

$5.8 million |

3 |

August 2020 to June 2022 |

|

National Defence |

Not applicable |

$22,000 |

$5.0 million |

3 |

August 2019 to February 2022 |

|

National Defence |

Not applicable |

$2.2 million |

$8.9 million |

3 |

August 2021 to March 2023 |

|

National Defence |

Not applicable |

$1.4 million |

$9.1 million |

2 |

August 2021 to April 2023 |

|

Subtotal |

Not applicable |

$3.7 million |

$28.8 million |

11 |

Not applicable |

Crown corporations

| Organization | Value of original competitive contract (before taxes) | Value of original non‑competitive contract (before taxes) | Approximate total value of chain of contracts (before taxes) | Number of non‑competitive contracts following the initial contract | Time period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Business Development Bank of Canada |

$2.1 million |

Not applicable |

$2.7 million |

1 |

November 2018 to April 2019 |

|

Business Development Bank of Canada |

$2.8 million |

Not applicable |

$5.7 million |

1 |

August 2021 to September 2022 |

|

Canada Post |

$3.7 million |

Not applicable |

$16.5 million |

7 |

January 2020 to July 2022 |

|

Export Development Canada |

$2.0 million |

Not applicable |

$4.2 million |

2 |

August 2020 to April 2021 |

|

Subtotal |

$10.6 million |

Not applicable |

$29.1 million |

11 |

Not applicable |

|

Total |

$10.6 million |

$3.7 million |

$57.9 million |

22 |

Not applicable |

5.45 We found that the use of non‑competitive approaches for subsequent contracts in these chains was poorly justified in several cases, specifically:

- Export Development Canada awarded subsequent contracts in 1 chain at least in part to complete work that had originally been required under the initial contract.

- Employment and Social Development Canada and Export Development Canada stated that they would compete subsequent contracts at one point in the chain but did not.

- Business Development Bank of Canada and Export Development Canada stated that competing later contracts in the chain would generate additional costs because work on the earlier contracts had given McKinsey & Company specific insight into their business. We found that cost savings were quantified for only 1 subsequent contract, by Export Development Canada, out of the 2 in our sample that provided this justification.

- National Defence and Employment and Social Development Canada each awarded 1 initial non‑competitive contract using the exception under the Government Contracts Regulations that the value of the contract was below the set dollar threshold. This resulted in the use of another exception for the subsequent contracts of considerably greater value.

5.46 The result of continuing to award non‑competitive contracts to the initial supplier may be perceived as an overreliance on that supplier, and opportunities to maximize value for money through competitive bids may be lost.

Opportunities to improve conflict‑of‑interest procedures

5.47 We found a range of practices across organizations to monitor and manage conflicts of interest in the procurement process:

- Export Development Canada was the only organization that had a proactive conflict‑of‑interest process in place for both competitive and non‑competitive procurements.

- Two other Crown corporations had a procurement-specific conflict‑of‑interest process in place for competitive procurements.

- For the Crown corporations that issued non‑competitive contracts, 7 of them did not have a conflict‑of‑interest process for non‑competitive procurements.

- Departments and agencies relied on annual conflict‑of‑interest declarations or proactive disclosures by employees.

- Conflict‑of‑interest declarations for bid evaluators were not on file for 7 of the 13 competitive contracts awarded by departments and agencies.

5.48 Conflict‑of‑interest declarations enable an organization to ensure that its interests are protected and that measures are in place to reduce any risks or biases, actual or perceived, to an acceptable level. Adopting a more proactive approach in these circumstances would be a better practice.

5.49 To effectively monitor and ensure that officials involved in the procurement process do not have conflicts of interest, all federal organizations that have not already done so should implement a proactive process to identify actual or perceived conflicts of interest in the procurement process and should retain the result of such a process and completed conflict‑of‑interest declarations in the procurement file.

The organizations’ responses. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Lack of enforcement of security requirements

5.50 Departments and agencies are subject to the Policy on Government Security, which sets expectations for classifying and safeguarding information. Of the 36 contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company by departments and agencies (Exhibit 5.1), 17 or 47% had a security requirement. We found that for 13 or 76% of these 17 contracts, the departments and agencies were not able to demonstrate that all the individual consultants had the appropriate security clearance needed to do the work in the contracts. For example, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada identified that 5 contractors had been granted access to its network without a valid security clearance.

5.51 Crown corporations are not subject to the Policy on Government Security. We found that 5 of the 10 Crown corporations did not have policies on information security. All Crown corporations included confidentiality clauses in contracts to protect sensitive information in the hands of contractors.

Organizations’ contracting practices often did not promote value for money

5.52 This finding matters because federal organizations need to ensure that public funds are spent with due regard for value for money, including in decisions about the procurement of professional services contracts.

The need for a contract was often not documented

5.53 In 15 (45%) of the 33 contracts in our sample for value for money, the procurement files lacked sufficient documentation to justify the need for a contract. We found that the files did not include an explanation of what need or gap the contract was intended to address.

5.54 We also found insufficient justification for amendments related to 1 Public Services and Procurement Canada contract. The amendments involved McKinsey & Company taking over tasks originally intended to be performed by the department after training federal employees.

Little initial assessment of estimated costs

5.55 In 30 (91%) of the 33 contracts in our sample, we found that the federal organizations did not perform sufficiently detailed cost estimate calculations before receiving proposals. Without first assessing the anticipated cost of a contract, an organization is not well positioned to determine whether to proceed with the procurement. For example, the organization cannot confirm

- whether the benefits provided by the contract’s deliverables outweigh the cost of the contract

- particularly for non‑competitive contracts where there are not multiple bids to compare prices, whether the price quoted provides value for the services proposed

Not all expected results from contracts delivered

5.56 We looked at the monitoring of contracts with 1 month in duration or longer. In our sample of 33 contracts, 26 met this profile. We found that 15 (58%) of the 26 contracts lacked evidence of ongoing monitoring of the progress of work. Monitoring is important for timely course correction to achieve the expected results of the contract and is particularly important in ensuring the accuracy of the amount charged by the vendor for work performed on an hourly or weekly basis.

5.57 We compared the deliverables to the associated contract statement of work to assess whether departments, agencies, and Crown corporations received the services in their contracts. We found that organizations did not receive all deliverables listed in the contracts for 6 (18%) out of 33 contracts. For 5 other contracts, we found that the statement of work was not specific enough for us to assess whether what was delivered was consistent with the contract requirements.

5.58 To maximize the value for money from a contract, all required deliverables should not only be received by federal organizations but also be useful and used to achieve the outcomes intended by the contracts. For 8 (24%) of the 33 contracts in our sample, we found that 3 did not achieve the intended outcomes, and for the other 5, we could not determine the intended outcome.

5.59 We also found that, in 2021, National Defence asked McKinsey & Company to send invoices before work was completed for 2 concurrent contracts: 1 in our sample of 33 contracts and 1 identified by the department’s own internal audit. Services were ultimately provided in both cases; however, department officials certified that the services were received and released payment before the services were delivered. This contravened the Financial Administration Act.

Insufficient challenge by Public Services and Procurement Canada as a common service provider

5.60 Public Services and Procurement Canada is the federal government’s central purchasing and contracting authority and common service provider for procurement. As such, when organizations use its services, the department is responsible for guiding the organizations toward appropriate practices when putting contracts in place or making use of centralized tools like standing offers or supply arrangements. However, we found that the department did not always fulfill this responsibility.

5.61 A standing offer is usually considered for goods and services when they are well defined and one or more clients repetitively orders the same range of goods and services but the actual demand (for example, quantity, delivery date, delivery point) is not known in advance. When Public Services and Procurement Canada is the contracting authority, it has a responsibility to ensure that the use of a standing offer is appropriate considering the services sought.

5.62 We found that, in November 2021, 2 contracts for National Defence under the national master standing offer included services beyond the scope of work that the standing offer was intended to cover. In our view, National Defence should not have used this procurement tool for this work, and Public Services and Procurement Canada should have challenged it when National Defence’s requirements exceeded the scope of the standing offer.

5.63 In addition, in 6 of the call‑ups against the national master standing offer, we found that the organizations did not have clear justifications for the contracts. In all of these cases, Public Services and Procurement Canada also did not fulfill its responsibility to ensure that there was an alignment between the call‑up and the national master standing offer.

5.64 We also found that, where Public Services and Procurement Canada was the contract authority for multiple contracts awarded on behalf of the same organization to the same vendor for a similar purpose and within a short period of time, the department did not challenge the departments about whether the procurement strategy used was appropriate.

Conclusion

5.65 We concluded that professional services contracts were often not awarded to McKinsey & Company in accordance with applicable policies. The federal organizations’ frequent disregard of policies and guidance was evident by missing bid evaluations and poorly justified use of non‑competitive approaches.

5.66 We further concluded that value for money for the professional services contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company was often not demonstrated. This occurred particularly when 1 or more of these elements were not clear: whether a contract was needed, what the expected deliverables were, whether all the deliverables were provided, or that the ultimate intent of the contract was achieved.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on professional services contracts. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether procurement of professional services contracts complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether professional services contracts were awarded to McKinsey & Company in accordance with applicable policies (procurement compliance) and whether value for money for those contracts was obtained.

Scope and approach

The audit assessed whether the awarding and management of professional services contracts complied with applicable procurement policy instruments. We relied on the internal audits and reviews of procurement compliance conducted by the organizations as required by the Office of the Comptroller General or requested by the President of the Treasury Board. We conducted additional audit procedures when reliance was not possible.

An assessment of the following elements of organizations’ internal audit or review work was done to determine whether we could rely on them:

- The objective, scope, and criteria for the internal work were suitable for our purposes.

- The internal work was properly planned and performed by employees having adequate knowledge, competence, and independence.

- The work of organizations’ employees was properly supervised, reviewed, and documented.

- Sufficient appropriate evidence was obtained to support the internal audit or review conclusions.

- The internal audit work and conclusions were appropriate in the circumstances, and the final report was consistent with the results of the work performed.

We also consulted with the Office of the Procurement Ombud, which conducted a review of the integrity and compliance of procurement processes, although only for federal departments and agencies.

The audit examined whether the procurement processes were conducted in a manner consistent with the policy instruments that were in place at the time of the procurement.

The key elements of procurement policy that we examined were

- the decision to opt for a non‑competitive rather than competitive procurement strategy

- the bid evaluation process

- contract management, such as approval of contracts and amendments

- certification of the receipt of services

We considered 5 elements to determine whether the organizations ensured that value for money was received for those contracts:

- whether the organization demonstrated that the contract was required

- whether the price was appropriate

- whether the contract clearly described the intended outputs

- whether the organization ensured it received what it paid for according to the contract

- whether the vendor’s services achieved the intended outcomes

The audit used the same cut‑off date for the contracts as the Office of the Comptroller General instructed departments and agencies to use in their internal audit work. That is, the audit scoped in all the contracts that departments, agencies, and Crown corporations awarded between 1 January 2011 and 7 February 2023. However, the audit period extended until 30 September 2023.

To assess compliance of the entire population of 97 contracts awarded, we examined 92 contracts for which documentation was available. The 5 excluded contracts were

To assess compliance of the entire population of 97 contracts awarded, we examined 92 contracts for which documentation was available. The 5 excluded contracts were

- 2 contracts that, as organizations reported, had not been retained because of information-retention policies

- 3 contracts whose documentation had been destroyed for policy reasons unrelated to this audit

To assess whether the 20 federal organizations ensured that value for money was received for the contracts within the audit period, we made the following adjustments to the list of 92 contracts as follows:

- removed 1 contract with no attached value that was awarded but never implemented

- removed 1 contract that was assessed for value for money and procurement compliance by the internal audit function of an organization

- merged 2 contracts that appeared to be related to the same engagement

We then selected a representative sample of 33 contracts awarded to McKinsey & Company since 1 January 2011 drawn from a population of 89 contracts—from 9 departments and agencies and 9 Crown corporations.

Departments, agencies, and Crown corporations are responsible for establishing retention periods for information and data. Library and Archives Canada recommends that financial information of business value (including contracts) be maintained for 6 fiscal years. This affected the availability of information, as the scope spanned more than 12 years.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Professional services contracts are awarded to McKinsey & Company in a fair, open, and transparent manner consistent with the legal and policy instrument that is in place at the time. |

|

|

The organization demonstrates that the contract is required. |

|

|

The organization demonstrates that the price is appropriate. |

|

|

The contract awarded clearly describes the contract’s intended outputs. |

|

|

The organization ensures that it receives what it paid for according to the contract requirements. |

|

|

The organization demonstrates that the vendor’s services achieve the intended outcomes. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 January 2011 to 30 September 2023. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 30 May 2024, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by Nicholas Swales, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendation and Responses

Responses appear as they were received by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada.

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

5.49 To effectively monitor and ensure that officials involved in the procurement process do not have conflicts of interest, all federal organizations that have not already done so should implement a proactive process to identify actual or perceived conflicts of interest in the procurement process and should retain the result of such a process and completed conflict‑of‑interest declarations in the procurement file. |

The Atomic Energy of Canada Limited’s response. Agreed. The Atomic Energy of Canada Limited agrees and will ensure that its conflict of interest declaration process is supplemented by a procurement-specific process that is in addition to its annual conflict of interest declaration process, and that proactive identification of any conflict is recorded in procurement files. The Bank of Canada’s response. Agreed. Bank of Canada procurement policies and processes have evolved since 2011, the date of our one contract with McKinsey & Company. The Bank of Canada has a proactive conflict of interest process embedded in the procurement cycle. All requisitioners and approvers are required to certify that they are free of conflict of interest at the purchase requisition stage, whether a competitive or non‑competitive procurement vehicle is used. Furthermore, all members of competitive contracting evaluation committees must complete a conflict of interest declaration to identify any perceived or actual conflicts, these declarations are assessed by independent procurement consultants before a member can proceed with a competitive contract evaluation. Proponents must also complete a conflict of interest declaration as part of their submission. Lastly, the Bank of Canada has an annual Code of Conduct compliance exercise that includes proactive disclosure on conflicts of interest. No further action is planned. The Business Development Bank of Canada’s response. Agreed. The Business Development Bank of Canada Procurement Policy refers to the Business Development Bank of Canada’s code of ethics, signed by all employees. Conflict of interest is addressed in this code to ensure professional impartiality in supplier selection. The Canada Development Investment Corporation’s response. Agreed. The Canada Development Investment Corporation (CDEV) agrees with the recommendation. Notwithstanding current requirements within CDEV’s procurement policy and standard request‑for‑proposal template to identify and declare conflicts of interest, CDEV will review its policies and practices by the end of Q3 2024 with a view to ensuring that a proactive process is in place to identify actual or perceived conflicts of interest. This may include requiring officials involved in the procurement process to make specific declarations that would be maintained in the procurement files, consistent with the recommendation. The Canada Infrastructure Bank’s response. Agreed. The Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) has adopted robust practices to identify and manage conflicts of interest. The CIB’s Procurement Policy provides that the procurement of goods and services must be completed responsibly and with the highest standards of integrity and ethical conduct in compliance with the CIB’s Code of Conduct and Conflict of Interest Policy. Each year, personnel are required to complete a compliance form to certify compliance with the code of conduct and disclose any private interest that could raise a real, potential or perceived conflict of interest. Personnel are also required to disclose conflicts of interest as they arise (whether or not the conflict was disclosed in the compliance form). To further improve the CIB’s processes regarding the documentation of conflict‑of‑interest declarations for the procurement of goods and services purchased by the CIB, the CIB will review the templates prepared to recommend contracts to authorized signatories to include a specific representation that personnel involved in the procurement do not have conflicts of interest regarding the procurement and any of the proponents invited to respond to the procurement opportunity. The CIB will implement this improvement by the end of Q2 Fiscal 2024‑25. Canada Post’s response. Agreed. Canada Post agrees with the recommendation. Canada Post’s Non‑Competitive Procurement Practice and Evaluation Guidelines document contains conflict of interest language.

Timing: Canada Post can implement this as a manual process within the next 6 months. Canada Post will require 6‑12 months to implement as an automatic process in Ariba. Destination Canada’s response. Agreed. Destination Canada has consistently followed the provisions of our Procurement Policy, as validated by the findings in this report. This includes proactively obtaining procurement-specific conflict of interest declarations from bid evaluators for competitively procured contracts. Additionally, annual proactive conflict of interest declarations are in place for staff. The results of these declarations are retained. This includes the bid‑evaluator declarations for a competitively procured contract, to which McKinsey and Company was awarded. In addition to securing conflict‑of‑interest declarations annually, Destination Canada will strengthen its procurement process to have declarations specific to each non‑competitive contract in Q3 2024. Export Development Canada’s response. Agreed. We agree with this finding and recommendation. While Export Development Canada has a process in place to pro‑actively identify, acknowledge, and make conflicts‑of‑interest declarations during the procurement process we plan to make further enhancements to our document retention processes and tools. While planned enhancements are expected in 2024, we are exploring a potential implementation of a workflow system solution to be implemented in 2025. The Public Sector Pension Investment Board’s response. Agreed. With respect to your recommendation to the organizations subject to the audit on improvements to their conflict of interest processes, we wish to reiterate that Public Sector Pension Investment Board already has a number of measures in place to prevent, detect and document conflicts of interest. In addition to quarterly and annual conflict declarations, employees and consultants are required to promptly notify our compliance department of any conflicts of interest as they arise, so that they can be addressed appropriately. While periodic conflict checks already occur with respect to our suppliers as a preventative measure in the context of the procurement process, the Public Sector Pension Investment Board is committed to reviewing its process to ensure that conflicts are addressed proactively prior to purchases, by the end of FY2025. The Trans Mountain Corporation’s response. Agreed. Conflicts of Interest (COI) notification requirements are addressed in Trans Mountain Corporation’s Code of Business Conduct and Ethics (the “Policy”). As a matter of course all employees are required to affirm their compliance with the Policy and identify any COI or perceived COI situations to their supervisors. The approach used by Trans Mountain Corporation documents and retains the employee’s annual electronic sign‑off. The onus is on the employee to take the initiative and report COI’s as they develop. The COI process does not distinguish between competitive or non‑competitive contracts. A COI is a COI and must be reported. We believe this process is effective as it engages all employees annually and reminds all of their duty to report COI situations when and if a COI arises. Trans Mountain Corporation also notes the importance ofdisclosing a COI if one exists. It is possible that circumstances change, in which case the annual certification is the disclosure control point. Senior Management will request Trans Mountain Corporation’s Internal Audit function review our COI control processes including the efficacy of adding incremental positive acknowledgements to our procurement process. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s response. Agreed. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat agrees with the recommendation. In exercising all duties, public servants, as a term and condition of employment, are required to uphold the Values and Ethics Code and adhere to the Directive on the Conflict of Interest. Building on this, as committed on March 20, 2024, and reiterated in Budget 2024, the Directive on the Management of Procurement has been amended to strengthen the management and oversight of government procurement with new mandatory procedures when contracting professional services. These new mandatory procedures will include a proactive process requiring business owners (managers) to certify that they acknowledge their responsibilities in managing the contract, they do not have a conflict of interest, that they have not directed which resources should be working under the contract, and that the contractor did not assist in or have unfair access to the solicitation process. The procedures provide an additional check and balance for public service managers to ensure that they are clear about their responsibilities and accountabilities when undertaking professional services procurement activities related to oversight, conflict of interest and values and ethics. All federal organizations subject to the Treasury Board Directive on the Management of Procurement will need to comply with this new procedure by no later than September 30, 2024. Together, these actions strengthen existing measures in place to ensure that those involved in a procurement process do not have conflicts of interest. |