2019 June Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the Yukon Legislative Assembly Independent Auditor’s ReportKindergarten Through Grade 12 Education in Yukon—Department of Education

2019 June Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the Yukon Legislative AssemblyKindergarten Through Grade 12 Education in Yukon—Department of Education

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

- 1—The percentage of Grade 7 students who met or exceeded expectations on the Yukon Foundation Skills Assessment was much lower for First Nations than for non–First Nations students

- 2—In spring 2017, a higher percentage of rural than urban Kindergarten students, particularly those from Yukon First Nations, needed more support in two or more areas of early learning

- 3—A much smaller proportion of Yukon First Nations students who entered Grade 8 in the 2011–12 school year completed high school within six years

Introduction

Background

1. The Yukon Department of Education delivers Kindergarten through Grade 12 public education to more than 5,000 students across Yukon. This includes distance education, home education, and education for students who need flexible learning options.

2. There are 28 schools across Yukon, with almost half based in small rural communities outside Whitehorse. According to the Department, more than half of rural students identify themselves as being from one of Yukon’s 14 First Nations.

3. There are no schools in Yukon for which Yukon First Nations have complete responsibility, but discussions are under way for Yukon First Nations governments to assume greater authority and control over education for their people.

4. Under the Education Act, the Department of Education is responsible for delivering an education system to Yukon students that will, among other things,

- encourage the development of basic skills and self-worth,

- provide students with opportunities to reach their maximum potential, and

- promote the language and culture of Yukon First Nations.

5. Similarly, the Department’s mandate, as described in the Yukon Education Strategic Plan 2014–2019, is “to deliver accessible and quality education to all Yukon learners.” However, the plan identified key challenges in meeting this mandate for Kindergarten through Grade 12 students, which included

- managing resources effectively in rural and urban schools,

- improving Yukon First Nations student achievement, and

- collaborating with Yukon First Nations governments.

6. In the 2016–17 fiscal year, the Department spent about 70%, or just under $117 million, of its operation and maintenance budget to deliver education programs in public schools. The Department of Education has the third-highest overall budget in the Government of Yukon.

Focus of the audit

7. This audit focused on whether the Department of Education delivered education programs that were inclusive and reflected Yukon First Nations culture and languages, and whether it assessed and addressed gaps in student outcomes.

8. This audit is important because education affects both the individual and Yukon as a whole. Well-educated citizens are more likely to be productive, healthy, and participating members of society and communities. With limited education, an individual faces fewer opportunities for jobs and civic participation. Therefore, it is critical that the education system work well for all students.

9. Of equal importance is that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, which documented the history and impacts of the Indian residential school system, called for improving education levels and success rates for Aboriginal peoples and for eliminating educational gaps between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians.

10. We did not examine the Yukon Francophone School Board or Yukon First Nations.

11. More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

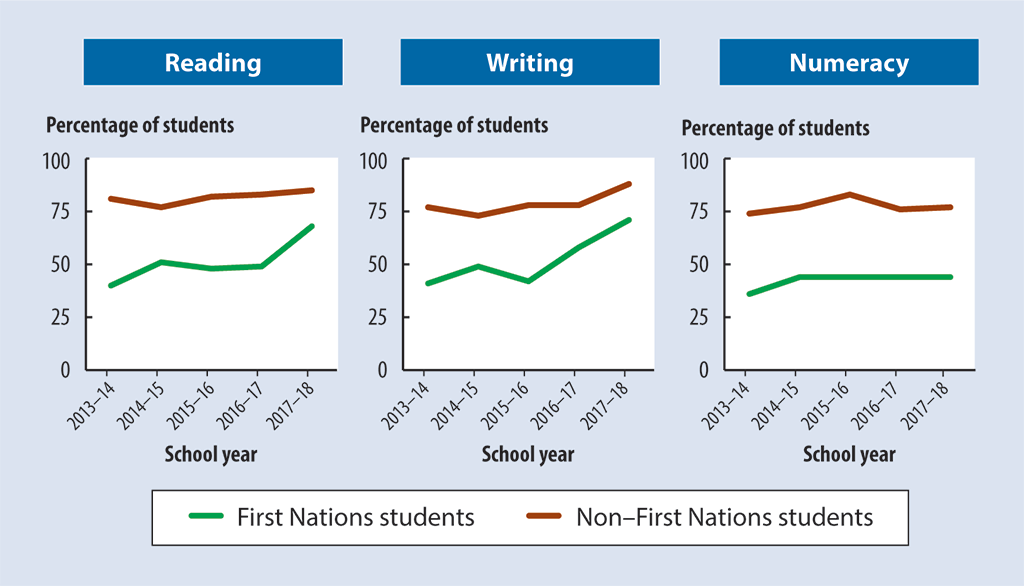

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

12. Overall, we found that the Yukon Department of Education did not know whether its programs met the needs of students, particularly those with special needs and those from Yukon First Nations.

13. We found that the Department still had not identified the underlying causes of long-standing gaps in student outcomes between First Nations and other Yukon students. These gaps included a lower high school completion rate for First Nations students compared with other students. We had a similar finding in an audit report we published in 2009.

14. We also found that the Department had not identified the underlying causes of the long-standing gaps in student outcomes between students in rural and urban schools. Until the Department understands the root causes driving these gaps, and the gaps in student outcomes between First Nations and other Yukon students, it has no way of knowing whether it is focusing its time and resources on where they are most needed.

15. With respect to inclusive education, we found that the Department did not monitor its delivery of services and supports to students who had special needs, nor did it monitor these students’ outcomes.

16. As a result, the Department did not know whether its approach to inclusive education was working, or whether it needed more focused attention on particular schools, groups, teachers, or subject areas. Half of the teachers who responded to our survey felt that they did not have the supports they needed to deliver inclusive education, and two thirds of those same teachers reported that they lacked sufficient training to do so.

17. In addition, and of equal importance, the Department has responsibilities and commitments to provide education programs that reflect Yukon First Nations culture and languages. Despite this, we found that the Department did not do enough to create a partnership with Yukon First Nations that would allow it to fully develop and deliver such programs. We also found that the Department did not provide enough direction, oversight, and support to help schools deliver culturally inclusive programming.

Education outcomes for Yukon students

18. Previous audit. In the 2009 January Report of the Auditor General of Canada, Public Schools and Advanced Education—Yukon Department of Education, we examined, among other things, whether the Department had effectively delivered public school programs to Yukon children and had a comprehensive plan to address student performance gaps.

19. In our 2009 report, we concluded that the Department could not demonstrate that it had effectively delivered public school programs, as required. We found that although the Department’s data showed gaps between First Nations and non–First Nations students on standardized math and language arts tests, the Department did not specify how large a gap warranted corrective action.

20. We also found that in most cases, the Department did not adequately analyze root causes, prepare action plans, or take corrective measures to help close those gaps.

21. In response to our audit recommendations in 2009, the Department of Education agreed to

- analyze data to identify critical trends and significant performance gaps;

- establish overall performance targets for Yukon students and, to the extent possible, for each major student subgroup;

- develop comprehensive action plans for significant gaps and relevant subgroups; and

- evaluate teaching staff on a timely basis.

22. Yukon First Nations school population. According to the Department’s documentation, for the 2016–17 school year, about 23% of the 5,342 Kindergarten through Grade 12 public school students were members of Yukon First Nations. The documentation also showed that Yukon First Nations made up about 16% of urban students, compared with about 53% of rural students.

The Department of Education did not do enough to understand and address long-standing gaps in student outcomes

23. We found that 10 years after our previous audit, gaps in student outcomes continued to exist between First Nations and non–First Nations students. We also found that gaps in student outcomes existed between rural and urban students.

24. We also found that the Department of Education had made little effort to identify the root causes of gaps in student outcomes to better understand them. Without this perspective, the Department could not ensure that its supports for students were the right ones to improve student outcomes.

25. Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Maximum potential not defined

- Gaps in student outcomes identified

- Little effort to understand root causes of gaps in student outcomes and no strategy to close the gaps

- Inadequate oversight

26. This finding matters because without identifying and understanding the root causes of long-standing gaps in student outcomes (such as test results) between First Nations and non–First Nations students, and between rural and urban students, the Department cannot ensure that it focuses its time and resources on where they are most needed. Nor can it determine what causes may be outside its control.

27. In addition, without a strategy to close the gaps in student outcomes, the Department cannot know how well it is addressing these gaps. If the Department waits too long to identify, understand, and address the root causes of these gaps, another generation of students could be affected for a lifetime.

28. Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 42 and 47.

29. What we examined. We examined how the Department of Education measured the performance of its public school system. We also examined whether the Department took informed and timely action to close the gaps it identified in First Nations and rural students’ performance and to improve student outcomes. Our discussion of student outcomes includes both student test results and high school graduation or completion.

30. Maximum potential not defined. Under the Education Act, the Department of Education is responsible for delivering an education system that provides students with opportunities to reach their maximum potential. However, we found that the Department of Education had not defined “maximum potential.”

31. For example, the Department did not define whether “maximum potential” meant the same for all students—whether it meant high school graduation, employability, or something else. Without targeting a precise outcome of reaching maximum potential, the Department cannot confirm that it is meeting its responsibilities under the Act.

32. Gaps in student outcomes identified. We found that the Department identified gaps in student outcomes between self-identified First Nations and non–First Nations students. These gaps were apparent in assessments such as the Yukon Foundation Skills Assessment, a test given to Grade 4 and Grade 7 students to assess the skills they had gained over several years. Results did not count toward students’ report card marks.

33. For example, we noted that the 2017–18 Yukon Foundation Skills Assessment statistics showed that for Grade 7 students, 68% of First Nations students met or exceeded reading level expectations, compared with 85% of non–First Nations students. In the same year, 44% of First Nations students met or exceeded numeracy level expectations, compared with 77% of non–First Nations students. Gaps in academic achievement between self-identified First Nations and non–First Nations students remained during the 2013–14 through 2017–18 school years, although they narrowed for reading and writing in 2017–18 (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1—The percentage of Grade 7 students who met or exceeded expectations on the Yukon Foundation Skills Assessment was much lower for First Nations than for non–First Nations students

Notes:

- First Nations identity was self-reported.

- In the 2017–18 school year, the Department relabelled the Yukon Foundation Skills Assessment results so that the “met expectations” category became “on track,” and the “exceeding expectations” category became “extending.” We chose to report the 2017–18 data using the previous categories, for ease of comparison with the 2013–14 through 2016–17 school years.

Source: Based on Department of Education documentation (unaudited)

Exhibit 1—text version

These 3 line charts show the percentages of First Nations versus non–First Nations students who met or exceeded expectations on the Yukon Foundation Skills Assessment for the 2013–14 through 2017–18 school years. Separate comparisons are shown for reading, writing, and numeracy. In each of these categories, the yearly percentages of First Nations students meeting or exceeding expectations were much lower than those of non–First Nations. These gaps remained during the 5-year period, although they narrowed for reading and writing in the 2017–18 school year.

The yearly percentages for the reading assessment were as follows.

| School year | Percentage of First Nations students meeting or exceeding expectations | Percentage of non–First Nations students meeting or exceeding expectations |

|---|---|---|

| 2013–14 | 40% | 81% |

| 2014–15 | 51% | 77% |

| 2015–16 | 48% | 82% |

| 2016–17 | 49% | 83% |

| 2017–18 | 68% | 85% |

The yearly percentages for the writing assessment were as follows.

| School year | Percentage of First Nations students meeting or exceeding expectations | Percentage of non–First Nations students meeting or exceeding expectations |

|---|---|---|

| 2013–14 | 41% | 77% |

| 2014–15 | 49% | 73% |

| 2015–16 | 42% | 78% |

| 2016–17 | 58% | 78% |

| 2017–18 | 71% | 88% |

The yearly percentages for the numeracy assessment were as follows.

| School year | Percentage of First Nations students meeting or exceeding expectations | Percentage of non–First Nations students meeting or exceeding expectations |

|---|---|---|

| 2013–14 | 36% | 74% |

| 2014–15 | 44% | 77% |

| 2015–16 | 44% | 83% |

| 2016–17 | 44% | 76% |

| 2017–18 | 44% | 77% |

Notes:

- First Nations identity was self-reported.

- In the 2017–18 school year, the Department relabelled the Yukon Foundation Skills Assessment results so that the “met expectations” category became “on track,” and the “exceeding expectations” category became “extending.” We chose to report the 2017–18 data using the previous categories, for ease of comparison with the 2013–14 through 2016–17 school years.

Source: Based on Department of Education documentation (unaudited)

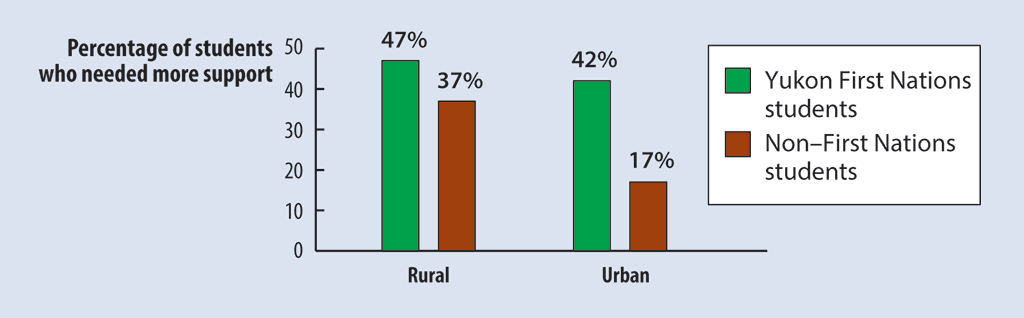

34. We found that the Department also did some work to identify gaps in student outcomes between rural and urban students. For example, the Department calculated the results of an early learning assessment for Yukon First Nations and non–First Nations rural and urban Kindergarten students in spring 2017. It looked at five areas of early learning associated with children’s readiness to learn at school, including their social, language, and motor skills.

35. Results indicated that a higher percentage of rural than urban Kindergarten students, particularly those from Yukon First Nations, needed more support in two or more areas of early learning (Exhibit 2). This analysis allowed the Department to see that, to some extent, the differences in assessment results might relate to whether students attended rural or urban schools.

Exhibit 2—In spring 2017, a higher percentage of rural than urban Kindergarten students, particularly those from Yukon First Nations, needed more support in two or more areas of early learning

Note: Data does not include First Nations who are not Yukon First Nations. Yukon First Nations identity was self-reported.

Source: Based on Department of Education documentation (unaudited)

Exhibit 2—text version

This bar chart shows the percentages of rural versus urban Kindergarten students who needed more support in 2 or more areas of early learning in spring 2017. In each of these 2 categories, separate data is given for Yukon First Nations and non–First Nations students. The chart shows that a higher percentage of Yukon First Nations students needed more support than non–First Nations students in both rural and urban schools.

| Percentage of Yukon First Nations students needing more support | Percentage of non–First Nations students needing more support | |

|---|---|---|

| Rural | 47% | 37% |

| Urban | 42% | 17% |

Note: Data does not include First Nations who are not Yukon First Nations. Yukon First Nations identity was self-reported.

Source: Based on Department of Education documentation (unaudited)

36. We found that the Department did not regularly break down many of its student outcome indicators on the basis of whether First Nations and non–First Nations students attended rural or urban schools. This prevented the Department from knowing whether attending a rural or urban school had an impact on student outcomes.

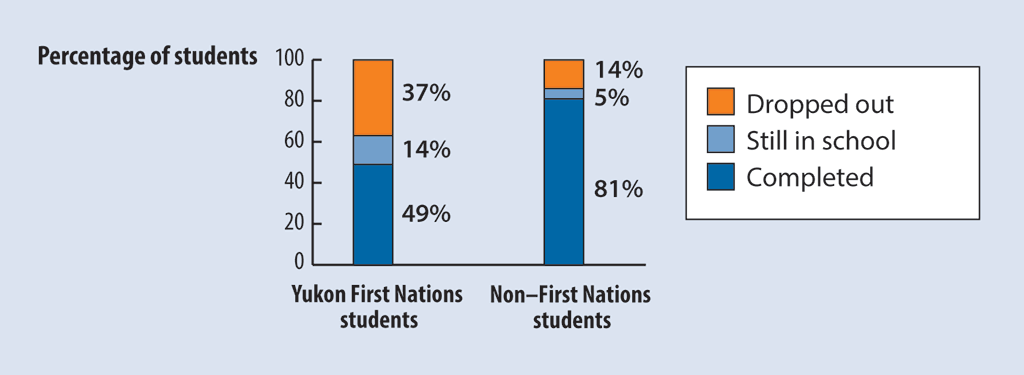

37. The Department also measured a six-year high school completion rate. This was the percentage of students who entered Grade 8 and went on to receive either a graduation certificate or a completion certificate within the next six years. Completion certificates were awarded to students who were unable to meet all graduation requirements because of their special needs. We found that for students who entered Grade 8 in the 2011–12 school year, the proportion who completed high school within six years was about 32 percentage points lower for Yukon First Nations students than for non–First Nations students (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3—A much smaller proportion of Yukon First Nations students who entered Grade 8 in the 2011–12 school year completed high school within six years

Notes:

- Data does not include First Nations who are not Yukon First Nations. Yukon First Nations identity was self-reported.

- These rates excluded students who left the Yukon school system to continue their education elsewhere.

Source: Based on Department of Education documentation (unaudited)

Exhibit 3—text version

This bar chart shows the percentages of Yukon First Nations versus non–First Nations students who entered Grade 8 in the 2011–12 school year and later dropped out, remained in school, or completed their high school education within 6 years.

| Academic outcome | Percentage of Yukon First Nations students | Percentage of non–First Nations students |

|---|---|---|

| Dropped out | 37% | 14% |

| Still in school | 14% | 5% |

| Completed | 49% | 81% |

Notes:

- Data does not include First Nations who are not Yukon First Nations. Yukon First Nations identity was self-reported.

- These rates excluded students who left the Yukon school system to continue their education elsewhere.

Source: Based on Department of Education documentation (unaudited)

38. Little effort to understand root causes of gaps in student outcomes and no strategy to close the gaps. We found that the Department did not understand the root causes of the long-standing gaps in student outcomes it had identified. Nor did the Department use its student data to help identify those causes.

39. We also found that the Department had no performance measurement strategy to set targets and guide its actions to close the gaps and help students meet their maximum potential. As a result, the Department could not establish targeted initiatives to address the root causes of the gaps and improve student outcomes.

40. Instead, the Department implemented initiatives to address gaps in student outcomes without understanding their root causes. For example, to improve outcomes for rural students, the Department offered a variety of learning programs, including the Rural Experiential Model—a week-long program with hands-on learning. While implementing such initiatives was a positive step, the Department did not know whether its efforts addressed the root causes of gaps in student outcomes.

41. We found that the Department recently developed some performance targets for students, which it had agreed to in response to our audit recommendation in 2009. However, these targets were not part of an overall strategy to close the gaps in student performance and improve student outcomes.

42. Recommendation. The Department of Education should develop and implement a strategy to address the long-standing gaps in student performance and improve student outcomes, particularly those of Yukon First Nations and rural students. The strategy should include

- analyzing the root causes of poor student outcomes,

- defining performance targets,

- developing and implementing actions to reach these targets, and

- evaluating the effectiveness of these actions to improve student outcomes.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education has gathered and published student performance indicators about Yukon students in Kindergarten through Grade 12, including urban, rural, and Yukon First Nations students. The Department acknowledges that it has not implemented a comprehensive strategy for measuring and analyzing differences in student outcomes and for targeting initiatives to address these differences.

During the 2019–20 school year, the Department will seek to collaborate with Yukon First Nations governments, which are in the best position to understand and respond to Yukon First Nations students’ educational needs, to develop and implement an outcome management improvement strategy for the Yukon education system. This strategy, which will also include the participation of education partners, will identify programs and activities to better assist students who may need more support to improve their learning outcomes at school. The strategy will also provide a framework of performance indicators and targets to track and measure student success and to evaluate program effectiveness.

43. Inadequate oversight. Yukon schools have to complete what the Department calls “school growth plans.” This is a process in which schools involve the parents, students, teachers, and local First Nations communities, all working together to improve students’ learning. The process includes setting goals and monitoring students’ progress.

44. We found that the Department did not submit a summary report of the school growth plans for the 2014–15, 2015–16, and 2016–17 school years to the Minister of Education, as the Department’s policy required. This meant that the Minister did not have this information, including information on how effective school strategies were in improving student outcomes.

45. According to the Department’s policy, all probationary teachers must receive a standard written evaluation in each of their probationary years, and all permanent school-based teachers must be evaluated at least once every three years.

46. However, we found that the Department did not complete most evaluations it identified as required in the 2015–16, 2016–17, and 2017–18 school years. This was despite the Department’s agreement to our 2009 recommendation to evaluate teachers on a timely basis. Without such evaluations, the Department has incomplete information on teacher performance.

47. Recommendation. The Department of Education should implement its required oversight mechanisms to provide summary reports to the Minister and complete teacher evaluations.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education is currently revising its School Growth Planning Policy. The Department will ensure that a process is in place for providing to the Minister of Education an annual summary of the goals, data trends, and objectives from school growth plans. This process will be developed and implemented by the end of the 2019–20 school year.

Over the course of 2019, the Department will implement an improved process for annually monitoring the completion of teacher evaluations. The revised process will align with the new collective agreement with the Yukon Teachers’ Association and will include requirements for completing and tracking teacher evaluations.

Inclusive education

48. Inclusive education in Yukon. The Department of Education establishes the curriculum and philosophy of education for all Yukon schools. The Department has stated that it is committed to inclusive education. It defines inclusion to mean that all students are entitled to equal access to learning, achievement, and the pursuit of excellence in all aspects of their education. According to the Department, the Yukon school model for inclusive education is based on the belief that all students can learn together in different ways.

49. The Department has responsibilities to take into account the needs of students who have intellectual, communicative, behavioural, physical, or multiple exceptionalities. Inclusive education includes supporting students who have special education needs in the classroom. This means that teachers may have to adapt classroom material, instruction, or assessment techniques to help students succeed.

50. School personnel identify students who may need specialized assessments. These students are referred to the Department’s Student Support Services Unit, whose specialists assess and identify students’ learning needs.

51. Student plans in Yukon. Students may receive plans to assist them in the classroom. This could include a student learning plan with targeted interventions within the regular curriculum, or a behaviour support plan that outlines strategies and supports for a student who has behaviour difficulties. A student plan could also be an individual education plan that identifies learning expectations that are adapted or modified from the regular curriculum.

52. According to the Department’s data, in the 2016–17 school year, 12% (or 619) of all students in Yukon had individual education plans. Proportionately more were from Yukon First Nations. The Department’s data showed that while 23% of Yukon’s student population identified themselves as being from Yukon First Nations, almost twice as many (42%) students with individual education plans were from Yukon First Nations.

53. When an individual education plan cannot be delivered within the regular classroom, the student can be admitted to an alternative setting called a “shared resource program.”

The Department did not know whether its approach to inclusive education was working

54. We found that the Department of Education did not know whether its approach to inclusive education was working. In particular, we found that the Department did not monitor the delivery of its services and supports for students who had special education needs. Nor did it monitor these students’ outcomes.

55. Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Supports needed to implement inclusive education not identified

- No reviews and evaluations on the overall approach to inclusive education

- No process to prioritize students who needed specialized assessments

- Poor oversight of services and supports for students who had special needs

56. This finding matters because if the Department does not know whether its approach to inclusive education is working, it cannot determine

- whether students and teachers are receiving the services and supports required for students to reach their maximum potential;

- whether any patterns in service use or outcomes might indicate particular schools, groups, teachers, or subject areas that need more focused attention from the Department;

- whether processes affecting students and teachers should be changed to improve the delivery of inclusive education; and

- whether there are adequate resources to respond to student needs in a timely manner.

57. Our recommendation in this area of examination appears at paragraph 70.

58. What we examined. We examined whether the Department of Education delivered inclusive education by establishing the services and supports needed to meet all students’ needs. As part of this, we examined

- how the Department assessed students who had special education needs, and

- whether the Department monitored and evaluated the impact of its services and supports to students identified as having special needs.

59. This work included surveying Kindergarten through Grade 12 public school teachers in Yukon to determine whether they thought the Department gave them suitable tools and resources to support their teaching responsibilities.

60. Supports needed to implement inclusive education not identified. We found that the Department did not identify the supports schools needed to implement inclusive education. Without this, the Department did not know whether teachers and other school officials had what they needed to support students.

61. For example, we found that although the Department’s annual report for 2017 showed a 31% increase in the number of educational assistants allocated to schools between the 2014–15 and 2016–17 school years, the Department could not determine whether this increase made any difference in teachers’ ability to implement inclusive education or improve student outcomes.

62. We also found that half of the teachers who responded to our survey felt that they did not have the supports they needed to deliver inclusive education. Supports could include guidance and training on how to adapt classroom material to help students better succeed. Supports could also include human resources, such as learning assistance teachers or counsellors in the schools. Furthermore, of the teachers who responded to our survey and said that they lacked necessary supports, 66% reported that they lacked training to implement inclusive education.

63. No reviews and evaluations on the overall approach to inclusive education. We found that by not reviewing and evaluating its overall approach to inclusive education and related outcomes, the Department did not exercise its leadership role. This included services and supports for students who had special needs. As a result, the Department did not know whether its approach to inclusive education was working.

64. No process to prioritize students who needed specialized assessments. We found that the Department lacked a process, including criteria, to prioritize which students would receive specialized assessments (such as from an educational psychologist or speech language pathologist). Department officials told us that some schools maintained wait-lists of students potentially needing specialized assessments. However, the lack of a prioritization process made it difficult for the Department to systematically identify students who had the most pressing needs from these wait-lists.

65. Poor oversight of services and supports for students who had special needs. We found that the Department did not track completed specialized assessments across the territory. Thus, it could not analyze the demographics—for example, what proportion of assessments were for First Nations or rural students. In addition, it could not know how long it took before students were assessed, or which students received an individual education plan after a specialized assessment.

66. We also found that the Department did not monitor the delivery of its services and supports across the territory to students who had special needs. Specifically, the Department did not track whether school staff implemented recommendations from specialists, or the outcomes of the specific plans and shared resource programs across the territory. Although the Department had information it could have used to analyze some high-level outcomes (such as graduation rates) for students who had an individual education plan, it did not do so.

67. At the school level, we reviewed 41 files of students who had individual education plans that covered both the 2015–16 and 2016–17 school years. These files were randomly sampled from five schools across Yukon. Over this two-year period, this meant that we examined 82 individual education plans in total. We examined whether students who had these plans got the services and supports that were identified as being needed. We also examined whether the students’ progress was monitored and plans were updated.

68. We found that of the 82 plans, only

- 4 (or 5%) showed that the services and supports recommended by specialists or school staff had been delivered,

- 2 (or 2%) had the required progress reports, and

- 5 (or 6%) had been reviewed and updated as required.

69. Our finding that the schools did not monitor progress on individual education plans was particularly troubling, given our previous finding 10 years ago that the Department did not formally measure students’ progress on these plans. Without such monitoring, the Department did not know whether students received, and benefited from, recommended services and supports, or whether the goals, objectives, and strategies for the students were actually met.

70. Recommendation. The Department of Education should conduct a full review of its services and supports for inclusive education. It should exercise a leadership role by, for example, engaging with teachers, parents, and specialists to determine how the Department can help teachers maximize student success. The review should include examining how best to

- evaluate whether its approach to inclusive education is working,

- determine whether services and supports are having the desired effect,

- determine whether sufficient resources are in place to support inclusive education,

- prioritize students for specialized assessments,

- assess and track specialist recommendations, and

- assess and track teachers’ use of recommended strategies.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education will seek to collaborate with Yukon First Nations governments to conduct an in-depth review of its services and supports for inclusive education. This review will ensure all students have access to quality education by addressing their diverse learning needs in a supported environment that allows them to meet their maximum potential. The review will start in fall 2019 and provide recommendations by spring 2020, and will result in the development of appropriate strategies, to be implemented starting in the 2020–21 school year.

The review will focus on inclusive education supports and services for Yukon students, including the delivery and monitoring of special education programs. The Department will seek to conduct the review in partnership with Yukon First Nations because they are best placed to understand and respond to their citizens’ educational needs and to direct targeted resources to support the success of First Nations students. The review will also consider perspectives from Yukon educators, parents, school councils, the Yukon Francophone School Board, and the Yukon Teachers’ Association, all of whom have important responsibilities in supporting students.

The Department notes that the actions it takes in response to other recommendations contained in this audit report will also improve its ability to provide inclusive education services and supports to all Yukon students.

Yukon First Nations culture and languages

71. The Department of Education’s approach to inclusive education is supposed to respect Yukon First Nations linguistic and cultural diversity, traditional knowledge, cultural practices, histories, and languages.

72. In the 2012–13 fiscal year, Yukon First Nations, the Government of Canada, and the Government of Yukon signed a Memorandum of Understanding on Education Partnership. The memorandum of understanding’s intent was to establish a partnership that would create and implement a joint action plan to help First Nations learners succeed.

73. In 2014, the Yukon First Nation Joint Education Action Plan 2014–2024 was created. The plan had four priorities. This audit focused on two:

- include the cultural and linguistic heritage of Yukon First Nations people in the curriculum, and

- have Yukon First Nations students meet and exceed academic requirements.

74. In 2016, the Government of Canada became a full supporter of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Article 14 of the Declaration recognizes that Indigenous individuals, particularly children, should have access, when possible, to an education in their own language and culture.

75. Requirements for Yukon First Nations languages. According to the Department’s documentation, all Yukon First Nations languages are critically endangered. To help promote these languages, the Education Act requires the Department of Education to establish policies and guidelines on the amount of instruction and the scheduling of Yukon First Nations language instruction in schools, in consultation with Yukon First Nations, school boards, and school councils.

76. Requirements for Yukon First Nations culture. The Education Act also requires schools, in consultation with Yukon First Nations, to include activities relevant to the culture, heritage, traditions, and practices of Yukon First Nations in school programs.

77. In September 2017, the Department of Education began implementing a new Kindergarten through Grade 9 curriculum that, in part, is intended to better reflect Yukon First Nations culture. The new curriculum was based on British Columbia’s redesigned curriculum.

The Department did not fully meet its Yukon First Nations culture and language responsibilities

78. We found that the Department of Education established some partnership structures to work with Yukon First Nations. However, we also found that despite these structures, the Department did not do enough to create a partnership with Yukon First Nations that would allow it to fully develop and deliver education programs that reflect Yukon First Nations culture and languages.

79. We also found that the Department did not provide enough direction, oversight, and support to help schools reflect Yukon First Nations culture and languages.

80. Our analysis supporting this finding presents what we examined and discusses the following topics:

- Partnership structures created

- No policy or strategic action plan to collaborate with Yukon First Nations

- Slow implementation of the Joint Education Action Plan

- No policy developed for Yukon First Nations language instruction

- Insufficient supports and resources to reflect Yukon First Nations culture and languages

- Inadequate cultural training

81. This finding matters because if the Department does not meet its legislative responsibility to reflect Yukon First Nations culture and languages in education programs, Yukon students cannot get the kind of education they are entitled to.

82. Furthermore, if education programs do not reflect Yukon First Nations culture and languages, the Department is not delivering inclusive education. Nor is it meeting its commitment to Yukon First Nations.

83. Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 89, 93, 99, and 109.

84. What we examined. We examined whether the Department of Education worked in partnership with Yukon First Nations to develop and deliver education programs that reflected First Nations culture and languages. This included assessing how the Department collaborated and consulted with the 14 different Yukon First Nations.

85. We also surveyed Kindergarten through Grade 12 public school teachers to understand their perspectives on the tools and resources the Department gave them to help carry out their teaching responsibilities. These included responsibilities for education programs to reflect First Nations culture and languages.

86. Partnership structures created. We found that the Department created various partnership structures to work with Yukon First Nations to develop and deliver education programs that reflected their culture and languages. For example, it achieved the following:

- It funded the Council of Yukon First Nations, the First Nations Education Commission, and the Yukon Native Language Centre for education-related deliverables. These included working with the Department and other education partners to improve learning outcomes for Yukon First Nations students. For the 2017–18 fiscal year, for example, the Department committed to funding the Council of Yukon First Nations in the amount of $260,000, the First Nations Education Commission in the amount of $175,000, and the Yukon Native Language Centre in the amount of $450,000.

- It established the First Nations Programs and Partnerships Unit to help reflect First Nations perspectives in Yukon’s school culture, curriculum, and programs.

- It signed one memorandum of understanding and four education agreements with 5 of the 14 Yukon First Nations and was working with 3 other Yukon First Nations to identify joint priorities in education.

- It met with the First Nations Education Commission—a body of Yukon First Nations representatives established to advance Yukon First Nations education interests—to work on implementing the Joint Education Action Plan.

87. No policy or strategic action plan to collaborate with Yukon First Nations. We found that the Department drafted a policy on how the Department and schools would collaborate with Yukon First Nations to meet the Education Act’s requirements. However, this draft policy did not include a related strategic action plan with specific, measurable actions and timelines to support this work. Such a plan is important for tracking progress in an accountable and transparent manner, and for showing how broader goals will be achieved. Given the Department’s legislated responsibilities, we would have expected it to have an approved policy and a related strategic action plan in place for its collaborative work with Yukon First Nations.

88. During our interviews with Yukon First Nations representatives, some told us that consultation and collaboration with the Department on education programs that are supposed to reflect Yukon First Nations culture and languages were not working well. For example, at times, the Department told them what it was going to do, rather than consulting with them to determine what should be done.

89. Recommendation. The Department of Education should complete and implement its policy to collaborate with Yukon First Nations to meet the Education Act’s requirements. It should also develop a strategic action plan with specific, measurable actions and timelines to support its work with Yukon First Nations.

The Department’s response. Agreed. Collaboration with Yukon First Nations governments on education priorities is essential to make sure that Yukon schools meet the needs of Yukon First Nations students and offer all Yukon students real opportunities to learn about Yukon First Nations languages, cultures, perspectives, and traditional knowledge.

Over the 2019–20 school year, the Department of Education will seek to partner with Yukon First Nations to complete and implement a policy for collaborating with Yukon First Nations to meet the requirements of the Education Act and to improve educational outcomes for Yukon First Nations students.

The Department will focus its strategic plans (for example, its Business Plan and its curriculum implementation plan) accordingly, and ensure that they have specific, measurable actions and timelines.

The Department has also established the position of Assistant Deputy Minister, First Nation Initiatives. This Assistant Deputy Minister will plan and organize the Department’s work to engage with Yukon First Nations governments and to implement agreed-to strategies at both the Yukon-wide and the local school levels.

90. Slow implementation of the Joint Education Action Plan. We found that the Department did not implement many of the partnership actions it was responsible for in the Yukon First Nation Joint Education Action Plan. For example, it did not pilot a First Nations language immersion Kindergarten program. Since the Joint Education Action Plan was established five years ago, we would have expected more progress.

91. Another initiative of the Joint Education Action Plan was to develop Yukon First Nations cultural inclusion standards in all schools. Together, the First Nations Education Commission and the Department defined and developed the standards. The intent of the standards was, among other things, to address systemic racism, improve learning environments for all students, and increase academic achievement rates.

92. We reviewed English schools’ reports on implementing these cultural inclusion standards. We found that schools implemented the standards to varying degrees. For example, staff at some schools participated in a mandatory annual orientation that the local First Nation developed and provided before the school year started, while other schools did not.

93. Recommendation. The Department of Education should meet regularly with Yukon First Nations to assess the status of the Joint Education Action Plan’s initiatives and determine how and when to complete those that remain.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education acknowledges there is room to improve and reinvigorate the work on the priorities identified in the Joint Education Action Plan, which has not yet been adequately implemented. The plan was jointly developed and endorsed by all 14 Yukon First Nations, the Government of Yukon, and the federal government.

The Department will seek without delay to resume meetings with Yukon First Nations and federal government representatives on this plan. The Department will seek to continue to meet on a regular basis, subject to agreement by Yukon First Nations, for the duration of this plan (that is, to 2024). At these meetings, the Department will seek to establish and prioritize agreed-to initiatives to implement the plan, both on a Yukon-wide basis and at the local community level; to agree to timelines; and to determine how to appropriately resource this work.

94. No policy developed for Yukon First Nations language instruction. We found that the Department did not establish policies or guidelines, including agreed-upon goals, on the amount and scheduling of Yukon First Nations language instruction in schools.

95. Department officials told us that the amount and scheduling of language instruction was determined primarily at the school level. They also told us that this determination could involve the principal, school council, local First Nation, and superintendent.

96. While it is important that schools, Yukon First Nations, and their local communities have some independence in determining their programs and activities, it is also essential that the Department uphold its responsibility to establish policies and guidelines to help ensure that language instruction occurs as required.

97. According to a language program review that the Department conducted for English schools, 20 schools offered Yukon First Nations language programs during the 2016–17 school year. These represented about 75% of Yukon’s English schools.

98. The language program review showed that an average of 38% of all students in Kindergarten through Grade 7 were enrolled in Yukon First Nations language classes. This enrollment rate dropped to 3% on average for grades 8 through 12. Department officials suggested that this was because the same content was taught year after year and students lost interest, but they did not conduct research to verify this.

99. Recommendation. In partnership with Yukon First Nations, school boards, and school councils, the Department of Education should develop policies and guidelines to support First Nations language learning. While developing the policies and guidelines, the Department should

- work with these partners to determine the language goals for individual schools;

- consider a range of approaches—for example, introductory classes to full immersion programs—that depend on the specific language, student population density, and community interest; and

- identify options to support Yukon First Nations languages both during regular school hours and outside the regular classroom.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education acknowledges the importance of meeting its obligation under subsection 52(5) of the Education Act. Under this subsection, the Department is to, in consultation with Yukon First Nations governments and school boards and school councils, establish approved policies and guidelines on the amount of instruction and timetabling for the instruction of Yukon First Nations languages.

The Department supports Yukon First Nations in their commitment to restore and revitalize their languages as a critical priority. The Department recognizes that revitalizing languages and restoring Yukon First Nations control over and responsibility for their languages are essential to the Government of Yukon’s work toward reconciliation.

The Department will seek to work with Yukon First Nations as well as with school councils and the Yukon Francophone School Board over the course of the 2019–20 school year to develop and implement a Yukon First Nations Language Instruction in the Schools Policy. This policy will support and enhance Yukon First Nations language learning in Yukon schools, with full consideration of the specifics of this recommendation.

100. Insufficient supports and resources to reflect Yukon First Nations culture and languages. We found that although the Department’s new curriculum aimed to better reflect Yukon First Nations culture, it did not have a human resource plan that identified the current and future resources needed to do so. Furthermore, we found that as of the 2016–17 fiscal year, the Department had not allocated any additional resources to the First Nations Programs and Partnerships Unit since the 2010–11 fiscal year.

101. Department officials in the Unit told us that they were expected to produce materials for the new curriculum but were under-resourced to do so. Department officials outside the Unit also told us that the Unit lacked the resources needed to help teachers reflect Yukon First Nations culture in the curriculum. Furthermore, the Unit has had no dedicated staff person for Yukon First Nations languages since 2016.

102. Although the Department gave teachers some Yukon First Nations cultural materials to help implement the new curriculum, Department officials told us that they had not yet developed Yukon First Nations cultural units for all grades. This meant that the teachers lacked what they needed to implement the new curriculum.

103. We found that program support for Yukon First Nations culture varied from school to school. For example, some schools reported that they had met the cultural inclusion standard to have at least one Yukon Indigenous land-based activity each season, while other schools reported no land-based activities at all. This underscores the importance of strong departmental oversight, so that all schools reflect Yukon First Nations culture in their programs.

104. We found that the Department gave teachers seven days of training in the 2017–18 school year on how to implement the new curriculum, including the First Nations components. Despite this, more than 50% of the teachers who responded to our survey did not feel that they had enough training to reflect First Nations culture in their teaching.

105. Similarly, more than 55% of the teachers who responded to our survey did not feel that they had the tools and resources needed to integrate First Nations culture into their teaching. Survey respondents indicated that it would be helpful to have

- access to First Nations Elders;

- a full-time First Nations cultural resource person in the school;

- workshops with clear ideas and examples of how to incorporate culturally appropriate resources into lessons;

- sample lesson plans for all subject areas and grades; and

- an organized, user-friendly, accessible list of resources linked to the new curriculum.

106. Inadequate cultural training. We found that cultural training for teachers included a mandatory one-day course intended to develop their understanding of and appreciation for Yukon First Nations history. Its delivery was agreed to as part of the Joint Education Action Plan.

107. Although this training was mandatory for all Department of Education staff, including those in schools, Department officials did not know exactly how many staff members had taken it.

108. According to the Yukon Bureau of Statistics, as of 31 March 2018, the percentage of teachers who identified themselves as being of Aboriginal descent was less than 20%. This could mean that some Yukon teachers entered the school system without understanding Yukon First Nations culture, making cultural training critical.

109. Recommendation. The Department of Education should determine the human resources and training required to develop sufficient classroom support and materials to help teachers implement the new curriculum as it pertains to Yukon First Nations culture and languages.

The Department’s response. Agreed. The provision of training, professional development, support, and materials is critical for successfully implementing the curriculum.

The Department will continue to develop and distribute modernized guidelines and materials to educators each year. This will include seeking as a priority to continue to work with Yukon First Nations to embed Yukon First Nations ways of knowing and doing in the new Kindergarten through Grade 9 curriculum and resources.

The Department will improve educators’ access to supports and materials over the 2019–20 school year. It will also provide collaborative professional development and training opportunities by

- setting common professional development and non-instructional dates in Whitehorse for collaborative learning, starting in the 2019–20 school year;

- having principals submit professional learning plans for their schools based on their staff’s learning needs about the new curriculum for the 2019–20 school year; and

- dedicating one professional development day in the 2019–20 school year for learning about Yukon First Nations ways of knowing and doing, with orientations from Yukon First Nations and reviews of Cultural Inclusion Standards for schools and school growth plans.

In the 2020–21 school year, the Department will gather feedback from educators on the implementation of the new curriculum. This feedback will determine what further training and supports are needed to ensure educators have the skills and knowledge they need to effectively deliver the modernized curriculum.

Conclusion

110. We concluded that the Department of Education did not do enough to assess or address the long-standing gaps in student outcomes.

111. We also concluded that the Department of Education did not do enough to deliver education programs that were inclusive and that fully reflected Yukon First Nations culture and languages.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on education in Yukon. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist the Yukon Legislative Assembly in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether the Yukon Department of Education’s public school system, Kindergarten through Grade 12, complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard for Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office applies Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit;

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit;

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided; and

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate.

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether the Department of Education delivered education programs that were inclusive and reflected Yukon First Nations culture and languages, and whether it assessed and addressed gaps in student outcomes.

Scope and approach

The audit focused on Yukon’s Kindergarten through Grade 12 public school system. Specifically, we examined whether the Department of Education adequately met key responsibilities for education in public schools in three key aspects of the education system: inclusive education, Yukon First Nations culture and languages, and student outcomes.

The audit approach included visits to eight Yukon public schools, as well as interviews and discussions with school staff, representatives from Yukon First Nations, and stakeholders.

The audit involved reviewing and analyzing key documents from the Department of Education. At the school level, we reviewed 41 files of students who had individual education plans that covered both the 2015–16 and 2016–17 school years. These files were randomly sampled from five schools across Yukon. Over the two-year period, this meant that we examined 82 individual education plans in total.

We surveyed teachers across Yukon’s 28 Kindergarten through Grade 12 public schools. The survey’s purpose was to collect teachers’ perspectives on whether the Department of Education’s tools and resources helped them fulfill their teaching responsibilities. We sent electronic questionnaires to 543 teachers and received completed responses from 181, for a total response rate of 33%.

We did not examine

- Yukon’s early learning and child care programs;

- Yukon’s adult education system, including Yukon College, other training or apprenticeship programs, and adult high school diploma programs;

- educational programs funded by the federal government;

- school councils;

- the Yukon Francophone School Board, which is responsible for the operation and management of the one French school in the territory; or

- Yukon First Nations.

Criteria

To determine whether the Department of Education delivered education programs that were inclusive and reflected Yukon First Nations culture and languages, and whether it assessed and addressed gaps in student outcomes, we used the following criteria:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Department of Education assesses the performance of its public school system to identify and measure gaps in students’ performance. |

|

|

The Department of Education takes informed and timely action to close the identified gaps in Yukon First Nations and rural students’ performance and improve their outcomes. |

|

|

The Department of Education works in partnership with Yukon First Nations to develop and deliver education programs that reflect Yukon First Nations culture and languages. |

|

|

The Department of Education assesses whether students have special educational needs so that it can set appropriate educational goals for them. |

|

|

The Department of Education delivers inclusive education so that all students have the services and supports they require. |

|

|

The Department of Education monitors the services and supports provided to students with special educational needs, so that it can adjust them as needed in order for the students to reach their maximum potential. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2018. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 23 April 2019, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Jo Ann Schwartz

Director: Marc Riopel

Alex Fontaine

Jenna Germaine

Ruth Sullivan

Marie-Ève Viau

Durriya Zaidi

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Education outcomes for Yukon students

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

42. The Department of Education should develop and implement a strategy to address the long-standing gaps in student performance and improve student outcomes, particularly those of Yukon First Nations and rural students. The strategy should include

(38 to 41) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education has gathered and published student performance indicators about Yukon students in Kindergarten through Grade 12, including urban, rural, and Yukon First Nations students. The Department acknowledges that it has not implemented a comprehensive strategy for measuring and analyzing differences in student outcomes and for targeting initiatives to address these differences. During the 2019–20 school year, the Department will seek to collaborate with Yukon First Nations governments, which are in the best position to understand and respond to Yukon First Nations students’ educational needs, to develop and implement an outcome management improvement strategy for the Yukon education system. This strategy, which will also include the participation of education partners, will identify programs and activities to better assist students who may need more support to improve their learning outcomes at school. The strategy will also provide a framework of performance indicators and targets to track and measure student success and to evaluate program effectiveness. |

|

47. The Department of Education should implement its required oversight mechanisms to provide summary reports to the Minister and complete teacher evaluations. (43 to 46) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education is currently revising its School Growth Planning Policy. The Department will ensure that a process is in place for providing to the Minister of Education an annual summary of the goals, data trends, and objectives from school growth plans. This process will be developed and implemented by the end of the 2019–20 school year. Over the course of 2019, the Department will implement an improved process for annually monitoring the completion of teacher evaluations. The revised process will align with the new collective agreement with the Yukon Teachers’ Association and will include requirements for completing and tracking teacher evaluations. |

Inclusive education

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

70. The Department of Education should conduct a full review of its services and supports for inclusive education. It should exercise a leadership role by, for example, engaging with teachers, parents, and specialists to determine how the Department can help teachers maximize student success. The review should include examining how best to

(60 to 69) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education will seek to collaborate with Yukon First Nations governments to conduct an in-depth review of its services and supports for inclusive education. This review will ensure all students have access to quality education by addressing their diverse learning needs in a supported environment that allows them to meet their maximum potential. The review will start in fall 2019 and provide recommendations by spring 2020, and will result in the development of appropriate strategies, to be implemented starting in the 2020–21 school year. The review will focus on inclusive education supports and services for Yukon students, including the delivery and monitoring of special education programs. The Department will seek to conduct the review in partnership with Yukon First Nations because they are best placed to understand and respond to their citizens’ educational needs and to direct targeted resources to support the success of First Nations students. The review will also consider perspectives from Yukon educators, parents, school councils, the Yukon Francophone School Board, and the Yukon Teachers’ Association, all of whom have important responsibilities in supporting students. The Department notes that the actions it takes in response to other recommendations contained in this audit report will also improve its ability to provide inclusive education services and supports to all Yukon students. |

Yukon First Nations culture and languages

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

89. The Department of Education should complete and implement its policy to collaborate with Yukon First Nations to meet the Education Act’s requirements. It should also develop a strategic action plan with specific, measurable actions and timelines to support its work with Yukon First Nations. (87 to 88) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. Collaboration with Yukon First Nations governments on education priorities is essential to make sure that Yukon schools meet the needs of Yukon First Nations students and offer all Yukon students real opportunities to learn about Yukon First Nations languages, cultures, perspectives, and traditional knowledge. Over the 2019–20 school year, the Department of Education will seek to partner with Yukon First Nations to complete and implement a policy for collaborating with Yukon First Nations to meet the requirements of the Education Act and to improve educational outcomes for Yukon First Nations students. The Department will focus its strategic plans (for example, its Business Plan and its curriculum implementation plan) accordingly, and ensure that they have specific, measurable actions and timelines. The Department has also established the position of Assistant Deputy Minister, First Nation Initiatives. This Assistant Deputy Minister will plan and organize the Department’s work to engage with Yukon First Nations governments and to implement agreed-to strategies at both the Yukon-wide and the local school levels. |

|

93. The Department of Education should meet regularly with Yukon First Nations to assess the status of the Joint Education Action Plan’s initiatives and determine how and when to complete those that remain. (90 to 92) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education acknowledges there is room to improve and reinvigorate the work on the priorities identified in the Joint Education Action Plan, which has not yet been adequately implemented. The plan was jointly developed and endorsed by all 14 Yukon First Nations, the Government of Yukon, and the federal government. The Department will seek without delay to resume meetings with Yukon First Nations and federal government representatives on this plan. The Department will seek to continue to meet on a regular basis, subject to agreement by Yukon First Nations, for the duration of this plan (that is, to 2024). At these meetings, the Department will seek to establish and prioritize agreed-to initiatives to implement the plan, both on a Yukon-wide basis and at the local community level; to agree to timelines; and to determine how to appropriately resource this work. |

|

99. In partnership with Yukon First Nations, school boards, and school councils, the Department of Education should develop policies and guidelines to support First Nations language learning. While developing the policies and guidelines, the Department should

(94 to 98) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. The Department of Education acknowledges the importance of meeting its obligation under subsection 52(5) of the Education Act. Under this subsection, the Department is to, in consultation with Yukon First Nations governments and school boards and school councils, establish approved policies and guidelines on the amount of instruction and timetabling for the instruction of Yukon First Nations languages. The Department supports Yukon First Nations in their commitment to restore and revitalize their languages as a critical priority. The Department recognizes that revitalizing languages and restoring Yukon First Nations control over and responsibility for their languages are essential to the Government of Yukon’s work toward reconciliation. The Department will seek to work with Yukon First Nations as well as with school councils and the Yukon Francophone School Board over the course of the 2019–20 school year to develop and implement a Yukon First Nations Language Instruction in the Schools Policy. This policy will support and enhance Yukon First Nations language learning in Yukon schools, with full consideration of the specifics of this recommendation. |

|

109. The Department of Education should determine the human resources and training required to develop sufficient classroom support and materials to help teachers implement the new curriculum as it pertains to Yukon First Nations culture and languages. (100 to 108) |

The Department’s response. Agreed. The provision of training, professional development, support, and materials is critical for successfully implementing the curriculum. The Department will continue to develop and distribute modernized guidelines and materials to educators each year. This will include seeking as a priority to continue to work with Yukon First Nations to embed Yukon First Nations ways of knowing and doing in the new Kindergarten through Grade 9 curriculum and resources. The Department will improve educators’ access to supports and materials over the 2019–20 school year. It will also provide collaborative professional development and training opportunities by

In the 2020–21 school year, the Department will gather feedback from educators on the implementation of the new curriculum. This feedback will determine what further training and supports are needed to ensure educators have the skills and knowledge they need to effectively deliver the modernized curriculum. |