2024 Reports 5 to 7 of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 7—Combatting Cybercrime

Report 7—Combatting Cybercrime

At a Glance

Overall, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Communications Security Establishment Canada, and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) did not have the capacity and tools to effectively enforce laws intended to protect Canadians from cyberattacks and address the growing volume and sophistication of cybercrime. We found breakdowns in response, coordination, enforcement, tracking, and analysis between and across the organizations responsible for protecting Canadians from cybercrime.

In 2022, victims of fraud reported financial losses totalling $531 million to the Canadian Anti Fraud Centre. Three quarters of these reports were cybercrime related. The centre estimates that only 5% to 10% of cybercrimes are reported. Without prompt action, financial and personal information losses will only grow as the volume of cybercrime and attacks continues to increase.

Effectively addressing cybercrime depends on reports going to the organizations best equipped to receive them. Those organizations need to act on the reports they receive to help protect Canadians against the risk of financial loss and other harms. While the RCMP, Communications Security Establishment Canada, and Public Safety Canada have discussed implementing a single point for Canadians to report cybercrime, this has yet to be implemented. Under the current system, people are left to figure out where to make a report or may be asked to report the same incident to another organization. For example, between 2021 and 2023, Communications Security Establishment Canada deemed that almost half of the 10,850 reports it received were out of its mandate because they related to individual Canadians and not to organizations. However, it did not respond to many of these individuals to inform them to report their situation to another authority.

In general, we found that Canada’s cybersecurity workforce needed to be strengthened across organizations. For example, the RCMP has struggled to staff its cybercrime investigative teams. As of January 2024, we estimated that almost one third of positions across all teams were vacant. In our view, having a plan to reduce human resource gaps across all responsible organizations is an important component of an updated National Cyber Security Strategy.

The RCMP has also experienced delays in deploying its National Cybercrime Solution, an information technology system meant to make it easier for victims to report cybercrimes, provide a shared cybercrime database for Canadian law enforcement agencies, and allow cross-referencing of domestic and international malware samples.

Key facts and findings

- The RCMP, through its National Cybercrime Coordination Centre, established partnerships with Canadian and international law enforcement to understand the needs of these agencies and coordinate efforts. However, it did not always forward to domestic police agencies requests for information it received from international partners.

- The RCMP and Communications Security Establishment Canada were often well coordinated in their responses to potential high priority cases, such as attacks on Government of Canada systems or critical infrastructure.

- In a report involving an offer to sell child sexual exploitation material, the CRTC did not refer the matter to law enforcement but rather told the complainant to contact law enforcement directly.

- In 1 instance, to avoid being served with a search warrant by a law enforcement agency, the CRTC deleted evidence and returned electronic devices on an accelerated time frame to a person being investigated for violating the anti‑spam legislation.

- The National Cyber Security Strategy developed by Public Safety Canada had critical gaps, such as the absence of the CRTC as a key player despite its mandate to enforce Canada’s anti spam legislation, which is directly linked to cybercrime.

Why we did this audit

- Canadian individuals, businesses, institutions, and infrastructure will continue to be targets for cybercriminals.

- Addressing cybercrime effectively depends on reports going to the organizations best equipped to receive them and on those organizations acting on the reports, thus helping protect Canadians against the risk of financial loss and other harms.

- Addressing cybercrime requires a coordinated approach, including federal entities, provincial and municipal governments, and the private sector.

Highlights of our recommendations

- The RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre should establish procedures to identify the most urgent victim notifications and ensure that they are sent first. The centre should set formal expectations for how fast victim notifications are sent, measure against these standards, and ensure that they are met.

- Public Safety Canada, the RCMP, Communications Security Establishment Canada, and the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission should work together to ensure that cybercrimes reported by Canadians and Canadian businesses are routed to the organization with the mandate to address them.

Please see the full report to read our complete findings, analysis, recommendations and the audited organizations’ responses.

Exhibit highlights

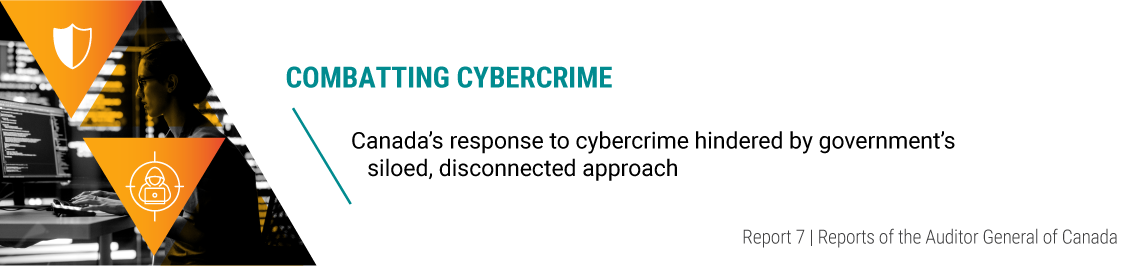

Federal organizations with cybercrime-related responsibilities

Source: Based on information from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Communications Security Establishment Canada, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, and Public Safety Canada

Text version

This flow chart shows the different federal organizations with cybercrime-related responsibilities and the ways that they are connected.

The largest branch is under the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, which is the lead federal organization that addresses cybercrime and investigates criminal offences that fall under its Federal Policing branch.

Under it are the following organizations:

- The Canadian Anti‑Fraud Centre, which helps Canadian citizens and businesses in reporting fraud, gathers intelligence on fraud across Canada, and assists police with enforcement and fraud prevention efforts.

- The National Cybercrime Coordination Centre, which cooperates with law enforcement and other partners to help reduce the threat and impact of cybercrime that targets Canadian companies.

- The Federal Policing branch, which works to provide protection to Canada and Canadians against domestic and international criminal threats, and cybercrime.

Under the Federal Policing branch is the Cybercrime unit, which investigates the most significant cyber‑threats to the federal government, national critical infrastructure, and key business assets.

The next branch is under Communications Security Establishment Canada, the national foreign intelligence agency and technical authority that provides support and advice on cybersecurity.

Under it is the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, which defends the federal government’s network; advises and assists other levels of government and the operators of Canada’s critical infrastructure, such as banks and telecommunications companies; and provides support for Canadian businesses.

Finally, there are the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission and Public Safety Canada.

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission enforces Canada’s anti‑spam legislation to have a safer and more secure online marketplace and reduce the harmful effects of spam and related threats on Canadians.

Public Safety Canada functions as a centralized hub for coordinating federal policy in a variety of areas, including cybercrime and cybersecurity.

The RCMP’s National Cybercrime Coordination Centre issued the majority of victim notifications within 1 day in 37 cases that we reviewed

| Time period | Number of victim notifications | Percentage of victim notifications |

|---|---|---|

| Issued within 1 day | 26 of 37 | 70% |

| Issued between 2 and 27 days | 9 of 37 | 24% |

| OtherNote * | 2 of 37 | 6% |

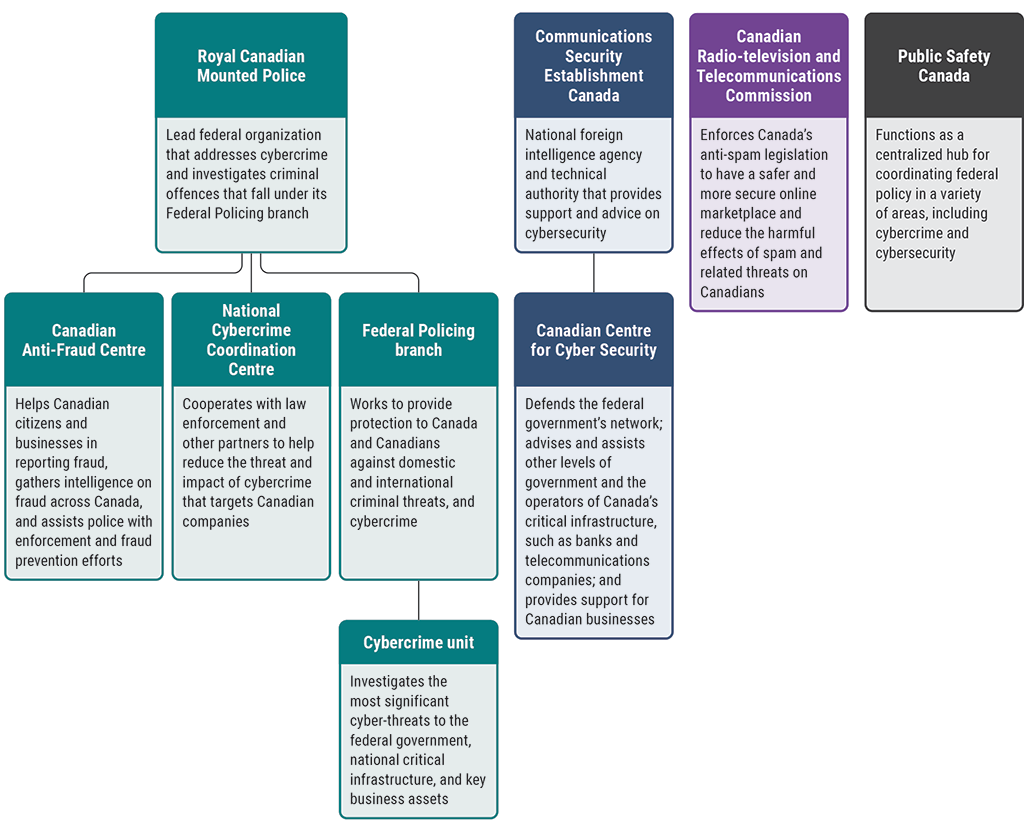

Public reporting of potential cybercrimes and other online threats in Canada

Source: Based on information from the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Text version

This list shows the ways that the public can report cybercrime and other online threats and is categorized by organizations included in the audit and those not included in the audit.

The following are organizations included in the audit:

- Law enforcement—The public can report potential cybercrimes to the municipal, provincial, or federal police (that is, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police). The only law enforcement agency included in the audit is the federal police.

- The Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s Canadian Anti‑Fraud Centre—The public can report potential fraud or cybercrimes, such as identity theft or scams.

- The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission—The public can report email or mobile text spam, including spam that enables cybercrime.

- Communications Security Establishment Canada—Organizations such as banks and hospitals can seek advice and guidance on cybersecurity through its Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, including when they have been the target of a cybercrime.

The following are other organizations not included in the audit:

- Competition Bureau Canada—The public can report goods purchased online that were misrepresented.

- The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada—The public can report concerns about email address harvesting and spyware.

- Cybertip.ca—The public can report information about online child sexual abuse and exploitation.

- The Canadian Security Intelligence Service—The public can report concerns about terrorism, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, espionage, foreign interference, or cyber-tampering affecting critical infrastructure.

Infographic

Text version

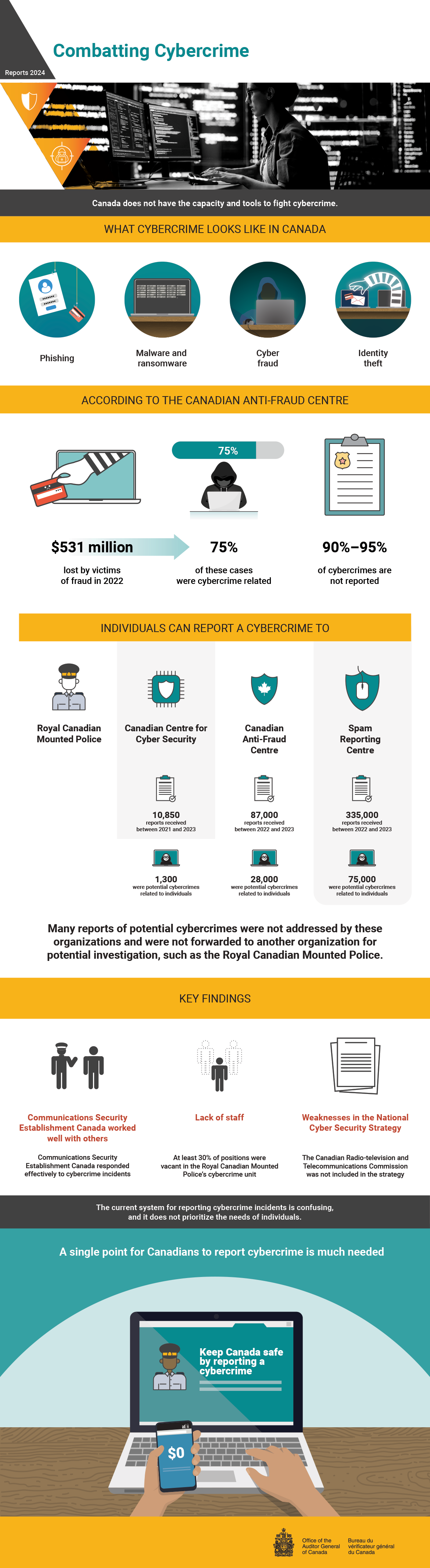

Combatting Cybercrime

Canada does not have the capacity and tools to fight cybercrime.

What cybercrime looks like in Canada:

- phishing

- malware and ransomware

- cyber fraud

- identity theft

According to the Canadian Anti Fraud Centre, $531 million was lost by victims of fraud in 2022, 75% of these cases were cybercrime related, and 90% to 95% of cybercrimes are not reported.

Individuals can report a cybercrime to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Communications Security Establishment Canada’s Canadian Centre for Cyber Security, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s Canadian Anti Fraud Centre, or the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission’s Spam Reporting Centre.

Between 2021 and 2023, the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security received 10,850 reports, of which 1,300 were potential cybercrimes related to individuals.

Between 2022 and 2023, the Canadian Anti Fraud Centre received 87,000 reports, of which 28,000 were potential cybercrimes related to individuals.

Between 2022 and 2023, the Spam Reporting Centre received 335,000 reports, of which 75,000 were potential cybercrimes related to individuals.

Many reports of potential cybercrimes were not addressed by these organizations and were not forwarded to another organization for potential investigation, such as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

There were 3 key findings:

- First, Communications Security Establishment Canada worked well with others. It responded effectively to cybercrime incidents.

- Second, there was a lack of staff. At least 30% of positions were vacant in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s cybercrime unit.

- Third, there were weaknesses in the National Cyber Security Strategy. The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission was not included in the strategy.

The current system for reporting cybercrime incidents is confusing, and it does not prioritize the needs of individuals.

A single point for Canadians to report cybercrime is much needed.

Keep Canada safe by reporting a cybercrime.

Related information

Entities

Tabling date

- 4 June 2024

Related audits

- 2022 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada

Report 7—Cybersecurity of Personal Information in the Cloud