2021 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of CanadaReport 1—Procuring Complex Information Technology Solutions

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

- Modernizing information technologyIT procurement

- Ensuring fairness and transparency in IT procurement

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- List of Recommendations

- Exhibits:

Introduction

Background

1.1 To deliver services efficiently, federal government organizations often need to procure new, complex information technology (IT) systems to replace aging ones. The government currently has about 21 large IT procurements underway, valued at over $6.6 billion.

1.2 In 2017, the Prime Minister directed the Minister of Public Services and Procurement to modernize how the government procures these new systems. Since then, Public Services and Procurement Canada and Shared Services Canada have introduced initiatives to meet this directive. Agile procurement, which they adopted in 2018, is one of them.

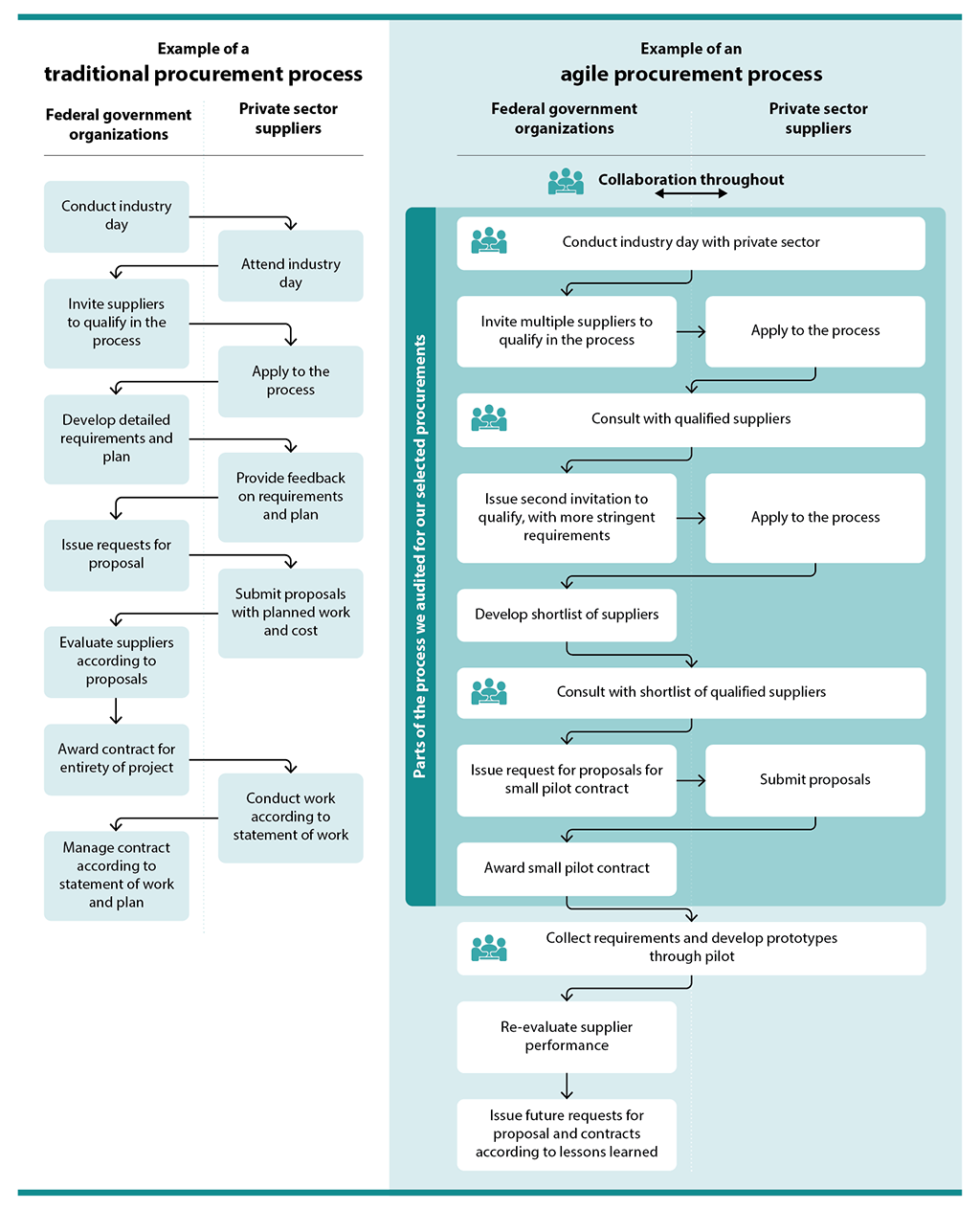

1.3 While the traditional procurement process is linear and awards a single large contract, the agile procurement process is iterative and awards multiple smaller ones (Exhibit 1.1). Agile procurement aims to achieve business outcomes by establishing close collaborations between procurement experts, end users (those who use the procured systems), and private sector suppliers through multiple phases. It permits course corrections and helps federal organizations apply lessons learned. It is best used for complex projects in which it may not be clear at the outset what the best potential solution is to address business needs.

Exhibit 1.1—Traditional versus agile procurement in the federal government

Exhibit 1.1—text version

This flow chart compares federal government examples of a traditional procurement process and an agile procurement process.

In a traditional procurement process, federal government organizations conduct an industry day, which private sector suppliers attend. Organizations invite suppliers to qualify in the process, and suppliers apply to the process. Organizations develop detailed requirements and a plan, and suppliers provide feedback on the requirements and plan. Organizations issue requests for proposal, and suppliers submit proposals with planned work and cost. Organizations evaluate suppliers according to proposals and award a contract for the entirety of the project. Suppliers conduct work according to the statement of work, and organizations manage the contract according to the statement of work and plan.

In an agile procurement process, organizations and suppliers collaborate throughout. Organizations conduct an industry day with the private sector and invite multiple suppliers to qualify in the process. Suppliers apply to the process. Both organizations and qualified suppliers consult on the process, and then organizations issue a second invitation to qualify with more stringent requirements. Suppliers apply to the process, and organizations develop a shortlist of qualified suppliers. Organizations consult with the shortlisted suppliers and then issue a request for proposal for the small pilot contract. Suppliers submit proposals, and organizations award a small pilot contract. Throughout the pilot, both the organizations and the suppliers collect requirements and develop prototypes. Organizations re-evaluate the suppliers’ performances and issue future requests for proposal and contracts according to the lessons learned.

For our selected procurements, we evaluated the agile procurement steps from the industry day to the awarding of the small pilot contract.

1.4 Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. The secretariat’s Office of the Comptroller General establishes the policies and standards for investment planning, projects, and procurements and leads these business areas. Its Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer puts in place policies and standards for training and developing federal public servants. Its Office of the Chief Information Officer provides strategic direction and leadership in IT and supports, guides, and oversees digital projects and programs.

1.5 Public Services and Procurement Canada. This department procures goods and services for federal organizations, from supplies and equipment to professional and consulting services. This includes all IT services above certain dollar thresholds, which vary by organization. It also develops procurement guidance that other organizations can use.

1.6 Shared Services Canada. This department provides digital services and solutions to other federal organizations. Many departments and agencies must work with Shared Services Canada to obtain services related to networks and network security, data centres and cloud offerings, digital communications, and IT tools.

1.7 Employment and Social Development Canada. This department develops, manages, and delivers social programs and services to Canadians, including Employment Insurance, the Canada Pension Plan, and Old Age Security. It is in the midst of procuring a new IT solution to implement a Benefits Delivery Modernization program, which will improve how it delivers these programs.

1.8 In 2018, we examined the implementation of the Phoenix pay system. We recommended that for all government-wide IT projects, there should be mandatory independent reviews of the project’s key decisions to proceed or not. We also recommended that an effective oversight mechanism should be established and should include the heads of concerned departments and agencies. Further, in February 2019, the Standing Committee on Public Accounts recommended that all IT transformation projects should have independent external oversight and that senior management in the concerned departments and agencies should take into account the interests of key stakeholders.

1.9 For this audit, we examined 3 major IT initiatives (Exhibit 1.2). We selected them because they used elements of an agile procurement process, are complex initiatives that include both software and professional services, are government-wide, and have a high impact on Canadians.

Exhibit 1.2—The 3 major IT initiatives examined in this audit

| Initiative | Business outcome | Progress to date | Estimated budget |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Next Generation Human Resources and Pay (NextGen) Lead organizationNote *: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (2018–20) and Shared Services Canada (as of April 2020) Contracting authorityNote **: Public Services and Procurement Canada |

Replace the government’s human resources and pay systems with a modern, digital solution that can provide employees with accurate, timely, and reliable pay. NextGen is expected to be a large, multi-year initiative, with multiple solutions piloted across government. |

In 2018, the Office of the Chief Information Officer at the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat began to explore options to replace the Phoenix pay system. In July 2019, the federal government awarded small contracts to 3 suppliers: Ceridian, SAP, and Workday, and in March 2020, the government announced SAP as the chosen supplier for a pilot with Canadian Heritage (the pilot was later announced in October 2020). In September 2020, the government awarded an additional contract to Workday for a pilot with Communications Security Establishment Canada. Planning for other pilots was also in progress. |

$117 million for pilot projects and program set-up Total value of initiative not yet estimated |

|

Benefits Delivery Modernization Lead organizationNote *: Employment and Social Development Canada Contracting authorityNote **: Public Services and Procurement Canada |

Develop a modern solution for the Employment Insurance, Canada Pension Plan, and Old Age Security programs to enhance client service, improve efficiency, make better-informed business decisions, and increase Employment and Social Development Canada’s agility to make changes to program policy and business rules. Benefits Delivery Modernization is expected to be a large, multi-year initiative and will be rolled out gradually across the 3 programs. |

In 2013, Employment and Social Development Canada began planning to replace its aging IT systems that process Employment Insurance benefits. In 2016, the department began its first industry consultation with a view to improving delivery of these benefits. In 2017, it expanded the initiative to include Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security benefits. In December 2019, an initial contract was awarded to IBM to develop a prototype of the core solution, and in 2020, it awarded small contracts to 4 other suppliers to help build the solution. |

$2.2 billion as of December 2020 |

|

Workplace Communication Services Lead organizationNote * and contracting authorityNote **: Shared Services Canada |

Consolidate and modernize the government’s telecommunications infrastructure to support a modern, standardized, reliable, and cost-effective voice service for organizations. |

In 2013, Shared Services Canada began planning to transform the government’s aging telecommunications network to a modern Voice over Internet Protocol solution. The department awarded a contract to Telus in June 2017 to build and implement the new technology in selected federal organizations. The project experienced delays and is now expected to be completed in 2026. |

$155 million |

Focus of the audit

1.10 This audit focused on whether the federal organizations responsible for procuring the 3 complex IT initiatives that we audited were on track to support the achievement of business outcomes and to uphold the government’s commitment to fairnessDefinition 1, openness, and transparency in procurement.

1.11 This audit is important because procurement is a key step in rolling out major IT initiatives. To carry out agile procurement processes effectively, the government must engage end users, suppliers, and decision makers; provide guidance and training; and ensure fairness and transparency. Procurements for major IT projects are inherently complex because of frequent changes in technology and business needs, ambitious timelines, and the need for technical expertise. As IT projects continue to increase in complexity and have a growing role and importance in government operations, the government has recognized that traditional procurement processes must be adapted to deliver solutions that achieve business outcomes.

1.12 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings, Recommendations, and Responses

Overall message

1.13 Overall, we found that the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Public Services and Procurement Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada, and Shared Services Canada made good progress toward adopting agile procurement practices for large IT systems. For example, they applied new procurement approaches and engaged with end users and private sector suppliers to define business needs and outcomes.

1.14 To pave the way for further progress, the organizations will need to build on these lessons and experiences with agile procurements. They will need to ensure that governance mechanisms are in place to meet business outcomes, and they will need to update their guidance and training for procurement officers, especially on how to apply new agile procurement methods. Better mechanisms for monitoring fairness, openness, and transparency in procurement are also needed to support the transition. These include using data analytics, improving information management practices for tracking fairness issues, and ensuring that the Fairness Monitoring Program supports the government’s commitment to promote fairness, openness, and transparency in the procurement process.

Modernizing IT procurement

1.15 The private sector, provincial governments, and other countries are moving toward agile procurement as a best practice for a variety of large and complex projects, including those focusing on IT.

1.16 In December 2018, the federal government’s Chief Information Officer published the Digital Operations Strategic Plan: 2018–2022. This plan established direction for the government on digital transformation, service delivery, security, information management, and IT. It encourages organizations to adopt agile, iterative, and user-centred methods when procuring customized digital solutions.

1.17 In 2019, Public Services and Procurement Canada released its Better Buying plan. The plan aims to deliver a simpler, more responsive, more accessible procurement system. The department has launched a number of initiatives to improve the procurement process, including agile procurement.

Federal organizations made good progress toward adopting agile procurement practices

1.18 We found that the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Public Services and Procurement Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada, and Shared Services Canada reviewed lessons learned from past projects and introduced new agile procurement practices. They subdivided megaprojects into smaller ones where possible and made good progress on consulting early and often with end users and private sector suppliers to gather their input on IT solutions.

1.19 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topic:

1.20 This finding matters because applying agile procurement methods—including engaging more closely with the organizations that will ultimately use the IT solutions—can help procurement teams better understand business requirements and design better solutions.

1.21 We made no recommendations in this area of examination.

Applying agile procurement approaches

1.22 We found that the procurement teams for the Next Generation Human Resources and Pay (NextGen) initiative and the Benefits Delivery Modernization program adopted a number of agile procurement practices. In particular, procuring organizations started with pilot projects, had live demonstrations and more testing to evaluate potential solutions, and added more flexibility with shorter contracts and multiple qualified suppliers.

1.23 For example, in September 2020, the government announced that it would pilot the development of a NextGen solution with Communications Security Establishment Canada, and in October 2020, it announced another pilot with Canadian Heritage. The procurement team also designed the contract to commit less time and funding upfront and to keep 3 qualified suppliers engaged after choosing a preferred supplier. Subdividing large IT initiatives into smaller projects, where possible, can reduce the risk of failure by incorporating early learning, while keeping multiple suppliers engaged can make it easier to rely on a back-up provider if the selected one fails to deliver.

1.24 For 2 of the procurements we examined—the NextGen initiative and the Benefits Delivery Modernization program—the procuring organizations had extensive consultations with end users, which were employees in a range of positions who would use the final product, such as payroll advisors. These user-experience consultations helped the organizations gather feedback on what would be needed from the new system to meet their business needs. The third procurement we examined—the Workplace Communication Services project—used a more traditional rather than agile procurement process, but it still included some agile elements, such as consulting with private sector suppliers to refine the requirements for the solution.

1.25 By better engaging end users on their business needs, the procurement team was better able to understand the suitability of the proposed IT systems before awarding contracts. For example, early in the NextGen procurement, the team created profiles of individuals that reflected the diversity of the system’s future users, and it developed a generic model of the functions that the system would need to perform. In a later phase, the team recruited 200 employees from various federal organizations and demographic groups to test the software packages and make sure that they were easy to use. In the final phases of the procurement, the team worked with dozens of specialists to develop scenarios to use when testing and evaluating the proposed systems.

1.26 The NextGen and Benefits Delivery Modernization procurement teams also engaged private sector suppliers early in the procurement process in an effort to create clearer solicitation documents. They invited suppliers to industry days, assessed their qualifications, and held one-on-one meetings and group sessions with them. The teams also adopted innovative techniques for evaluating proposals, such as requiring live demonstrations and testing products early in the evaluation process to make sure that the proposed product could perform key functions to meet business needs.

1.27 We asked selected private sector suppliers involved in the NextGen, Benefits Delivery Modernization, and Workplace Communication Services procurements for their perspectives on how the federal organizations used agile procurement practices. They told us that agile procurement was far more interactive and transparent, which was beneficial for meeting business outcomes.

Federal organizations rolled out agile procurement without sufficient training for staff or engagement with key stakeholders

1.28 We found that, although the federal organizations showed enthusiasm for agile procurement processes, Public Services and Procurement Canada and Shared Services Canada did not provide sufficient guidance or training to employees on how to conduct agile procurement for major IT initiatives, including how to effectively collaborate and respond to suppliers’ questions and feedback.

1.29 We also found that there were opportunities to improve governance mechanisms in order to meet desired business outcomes. For example, for the Benefits Delivery Modernization program, Employment and Social Development Canada’s governance structure lacked clear accountabilities. And for the Workplace Communication Services project, Shared Services Canada did not take into account the technology needs of National Defence, the project’s key stakeholder.

1.30 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Collaboration with suppliers needs improvement

- Insufficient guidance and training

- Opportunities to strengthen governance

1.31 This finding matters because agile procurement processes include more collaboration with suppliers than traditional methods do. Without adequate training, procurement teams may be ill-equipped for these interactions. Also, lack of engagement with key stakeholders in governance mechanisms can lead to problems that are costly and time consuming to solve after contracts are awarded.

1.32 In collaborative procurement processes, federal organizations and private sector suppliers interact more frequently to work together to iteratively design procurements that are focused on outcomes. For example, suppliers can provide comments or ask for clarifications about business or technical requirements.

1.33 The June 2018 report of the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates on modernizing federal procurement noted that shortcomings in training and recruitment were creating risks for procurement staff, their organizations, and Public Services and Procurement Canada. The report recommended that the government train procurement staff and help them develop expertise in agile approaches and that organizations recruit more procurement specialists.

1.34 In July 2020, Public Services and Procurement Canada, in consultation with Shared Services Canada, developed an Agile Procurement Playbook. The playbook introduces basic concepts and describes some of the uses and benefits of agile procurement.

1.35 The federal government learned the following important lessons about oversight and user engagement from the Phoenix pay system project:

- The government needs a single point of accountability for projects, with independent reviews of decisions and clear and comprehensive information for decision makers.

- It must be clear who the end users are, and the system must be designed with their participation and be focused on their needs.

- Federal organizations should award contracts on the basis of users’ desired business outcomes—not just on technical requirements—and should regularly confirm that their procurement activities support the business need.

1.36 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 1.47 and 1.53.

Collaboration with suppliers needs improvement

1.37 We found that the way in which procurement teams collaborated with private sector suppliers on proposed IT solutions needed improvement. In the procurements we examined, a collaborative approach was used with suppliers to define requirements for IT solutions.

1.38 We reviewed a random sample of supplier questions and comments and corresponding responses in the NextGen, Benefits Delivery Modernization, and Workplace Communication Services procurement files. In all 3, we found instances in which procurement teams’ responses to suppliers’ questions were incomplete, lacked rationale, or did not provide clear answers. These findings were true for a number of responses in the samples for each procurement, including

- 7 out of 22 (32%) of responses to supplier questions and comments for NextGen

- 6 out of 22 (27%) of responses to supplier questions and comments for Benefits Delivery Modernization

- 9 out of 22 (41%) of responses to supplier questions and comments for Workplace Communication Services

1.39 For example, in the NextGen procurement, a supplier requested clarification on the process and standards used to test the technology, but the procurement team did not provide a clear answer. It merely said that the supplier could “review any testing results.” A more complete answer could have enhanced communication and collaboration between the federal organization and suppliers to improve the business outcome.

1.40 We asked the procurement teams at both Public Services and Procurement Canada and Shared Services Canada why some responses were missing or lacked sufficient justification in the logs we reviewed. For some cases, the teams said they could not find any supporting documentation or that the solicitation documents had been changed after verbal discussions with suppliers—or without corresponding with suppliers again—and that the discussions had not been documented.

1.41 We also surveyed 181 suppliers involved in the NextGen, Benefits Delivery Modernization, or Workplace Communication Services procurements about their experiences with the question-and-answer process. The 40 suppliers who responded, on average, told us that the answers they received from procurement teams were only somewhat clear or complete. Some of the suppliers said that this hindered their ability to respond effectively and reduced their trust in the process. In follow-up interviews, suppliers described several other problems:

- Procurement teams did not provide answers or suggestions in a timely manner.

- The appropriate federal organization officials did not always answer the questions, so answers sometimes lacked sufficient detail.

- Procurement teams did not always consider suppliers’ feedback and suggestions, and the procurement team provided no rationale for this.

Insufficient guidance and training

1.42 We found that the guidance and training provided to officers on agile approaches was limited or non-existent. Although Public Services and Procurement Canada published its Agile Procurement Playbook introducing basic principles, the document did not provide a clear definition of agile procurement nor did it provide step-by-step guidance on how the key concepts of agile procurement could be applied, such as examples of best practices in collaborating with private sector suppliers. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and Public Services and Procurement Canada told us that they were reviewing and updating procurement policies, guidance, and training.

1.43 We also found that Shared Services Canada had developed some early training related to agile procurement, but it still had work to do to determine what guidance to develop. In 2019, the department created a team of 8 employees to simplify procurement processes and develop guidance and tools on agile procurement. It also conducted a gap analysis of the skills that would need to be upgraded to support agile approaches. But at the time of our audit, the team had not decided what guidance was needed or how to address knowledge gaps.

1.44 We interviewed procurement and program officials from Public Services and Procurement Canada and Shared Services Canada who had been involved in the selected procurements in our audit. They emphasized the need for clear guidance on what agile procurement is, how to apply it, and what must be done to maintain fairness, openness, and transparency of communications.

1.45 We noted that other jurisdictions issued more comprehensive guidance to employees on how to apply agile approaches. Here are some examples:

- In the United States, in 2016, the State of California’s Department of Technology began developing an agile framework to provide practical guidance on managing incremental project delivery. In 2020, the United States Department of Defense produced a series of detailed guidebooks to help staff develop strategies for acquiring IT systems using agile approaches.

- In the United Kingdom, in 2019, the Cabinet Office developed a framework and self-assessment tool to guide capacity building in procurement activities.

1.46 At the time of our audit, all federal procurement staff were expected to complete 6 courses through the Canada School of Public Service within 6 months of being appointed. The courses cover the basic concepts and responsibilities in government procurement projects and review legal and policy requirements. We found that this training did not include any topics related specifically to complex IT or agile procurement. We also reviewed procurement manuals and training materials and found that they did not explain how procurement teams should collaborate with suppliers or capture their exchanges when using agile procurement methods. Lastly, we found that Public Services and Procurement Canada did not assess what skills or competency training was needed to support the move to agile procurement, and that Shared Services Canada was just beginning this process.

1.47 Recommendation. To further support the government’s modernization of procurement,

- the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Public Services and Procurement Canada, and Shared Services Canada should develop more comprehensive guidance and training for employees to improve understanding of agile procurement and how to apply collaborative methods

- the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, with input from Public Services and Procurement Canada and Shared Services Canada, should also assess what skills, competencies, and experience procurement officers need to support agile approaches to complex IT procurements

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s response. Agreed. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat will continue to work with Public Services and Procurement Canada, Shared Services Canada, and other key stakeholders to develop, deliver, and promote formal and informal learning focused on agile procurement as well as develop and promote guidance and tools that support capacity building in the procurement community.

Public Services and Procurement Canada’s response. Agreed. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Public Services and Procurement Canada, and Shared Services Canada are working closely together to successfully implement transformational IT procurements and fostering a common understanding of agile procurements. Work on agile procurement has been done in close partnership, in addition to engaging with other government departments that are procurement clients.

Public Services and Procurement Canada will work in collaboration with the secretariat with respect to assessing the skills and competencies needed to support agile approaches to complex IT procurement. In addition, the department has a robust general procurement training regime in place for its procurement officers. The department has also undertaken significant efforts to further develop and launch guidance specific to agile procurement, as well as establishing a centre of expertise to support procurement officers in implementing this approach for public procurement. Guidance for procurement officers will continue to be refined and evolve, and as more procurements are undertaken using the agile procurement approach, opportunities will be identified to enhance training and other supporting tools. The department will complete this work by the fourth quarter of the 2022–23 fiscal year.

Shared Services Canada’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada is working closely with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and Public Services and Procurement Canada with respect to undertaking transformational IT procurements and is fostering a common understanding of agile procurements. Work on agile procurement has been done in close partnership and through engagement with other government departments that are Shared Services Canada’s procurement clients.

In December 2019, Shared Services Canada established the Centre of Expertise in Agile and Innovative Procurement, which is dedicated to supporting procurement officers in the implementation of agile and innovative procurements. The department has also undertaken significant efforts to launch and implement the Procurement Refresher and Essentials Program (PREP), which is continuously modernized. Shared Services Canada will continue to ensure that employees involved in transformational IT procurements have a more comprehensive understanding of agile and collaborative procurement methods through refinements to guidance, training, and support being provided to procurement officers.

Opportunities to strengthen governance

1.48 We found that governance mechanisms to engage senior representatives of federal organizations in the 3 complex IT procurements we looked at could be strengthened. The Policy on the Planning and Management of Investments requires deputy heads to ensure that the governance of projects and programs provides for effective and timely decision making and oversight. It also requires that projects and programs take into account the interests of all key stakeholders and focus on achieving business outcomes. Engaging senior representatives of concerned departments and agencies is critical to achieving the desired business outcomes as we had recommended in our 2018 audit of the implementation of the Phoenix pay system.

1.49 We found that Employment and Social Development Canada had not established a clear governance structure for the Benefits Delivery Modernization program. In 2019, an independent review of the program reported unclear accountabilities and gaps in the program’s formal processes for decision making. In response to the review, the department developed a draft governance framework. But by the end of our audit period, the department had still not formalized it—even though the department had selected and awarded a pilot contract to a supplier for the program’s core technology in December 2019.

1.50 For the Workplace Communication Services project, we found that Shared Services Canada did not engage National Defence, its first and largest client, in the governance, planning, and decision making until just before it awarded a contract (Exhibit 1.3). While Shared Services Canada had set up project governance for the Workplace Communication Services project, it did not include National Defence’s senior representatives even though National Defence would be the final users of the new technology. Shared Services Canada solicited input from suppliers on the core technology during the procurement process, but the department did not take into account National Defence’s interests and solicit input from this key stakeholder about its technology needs—a gap that resulted in National Defence not achieving its desired business outcomes. National Defence would no longer receive many of the originally planned features, such as desktop video conferencing, collaboration, and instant messaging, as part of this procurement.

Exhibit 1.3—Case Study: Shared Services Canada’s lack of engagement in key areas with National Defence caused problems for the Workplace Communication Services project

The government-wide Workplace Communication Services project, led by Shared Services Canada, was initiated in 2013, before the federal government began its move toward agile procurement. Nevertheless, the outcome of the project for National Defence is an instructive study on what can go wrong when federal organizations do not sufficiently engage key stakeholders to meet their business outcomes.

- In 2013, Shared Services Canada launched a procurement to convert the government’s aging voice telecommunications systems to a new service employing Voice over Internet Protocol technology. National Defence’s physical and network infrastructure would need upgrades before the conversion; however, Shared Services Canada did not plan for those upgrades until just before it awarded the contract in 2017.

- Because of this oversight, National Defence discovered late in the project that extensive additional work would be needed (with associated costs) for the new system to function.

- Because of the lack of available funding for this extra work, the scope of the proposed telecommunications solution had to be scaled back in 2019 to exclude a number of features that were central to National Defence’s desired business outcome, such as desktop video conferencing, collaboration, and instant messaging. These features will now need to be provided through separate contracts.

- By August 2020, the project had still not been delivered to National Defence, and Shared Services Canada was still gathering end-user requirements and seeking alternate solutions. National Defence told us that its voice services continue to experience serious issues at more than a dozen base, wing, and garrison sites, with outages that have lasted up to 14 days. Vendor support for the department’s old phone system ended in January 2018.

1.51 For the NextGen initiative, we found that there was engagement with senior representatives of concerned departments and agencies. The initiative was set up in June 2018, and the NextGen team began to engage the Deputy Minister Pay Modernization Committee in October 2018. One of this committee’s mandates was to provide advice and guidance on the NextGen initiative until the committee was dissolved in September 2019. In June 2019, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat set up a new governance committee—the Deputy Minister Committee on Core Services. Its mandate is to enable and support the decision making of departmental deputy heads responsible for the modernization of core services—including the NextGen initiative. Continued engagement of senior representatives in this committee will be essential in order for NextGen to achieve its desired business outcome of providing government employees with accurate, timely, and reliable pay.

1.52 We also asked private sector suppliers involved in the procurements we audited whether they found the federal organizations’ procurement roles and accountabilities to be clearly defined. Collectively, suppliers involved in the NextGen, Benefits Delivery Modernization, and Workplace Communication Services procurements told us that it was not always clear how concerned departments were involved in decision making on the scope and approach of the IT initiative, and that this resulted in unmet expectations and poorly understood decisions.

1.53 Recommendation. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Employment and Social Development Canada, and Shared Services Canada should ensure that governance mechanisms are in place to engage senior representatives of concerned departments and agencies for each of the complex IT procurements we audited. This will be particularly important to support agile procurements of complex IT initiatives and their successful achievement of business outcomes.

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s response. Agreed. For the Next Generation Human Resources and Pay initiative, the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer in the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat will continue to work with Shared Services Canada and departments and agencies at senior levels as well as users from the human resource, pay, and manager communities to define business needs and anticipate change management requirements.

As the initiative moves from discovery to more substantive phases, decision makers will be required to be engaged thoroughly. A review of existing governance to align it with upcoming phases is underway.

Employment and Social Development Canada’s response. Agreed. At the time of the audit, the governance structure was in development in parallel with the remainder of the Benefits Delivery Modernization program but was not yet finalized. As of February 2021, there is a finalized and approved governance structure.

The program has an effective stakeholder engagement mechanism with documented and communicated roles and responsibilities. The governance function is undergoing a refresh in preparation for Tranche 1 of the program. The revised structure adopts a holistic approach that integrates stakeholders through decision-making bodies, decision-making individuals, and bodies with advisory and assurance roles. Together, the participation of stakeholders across multiple forums ensures that the initiatives have the support they need to move forward and that business outcomes are met.

Shared Services Canada’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada is pleased to report that processes are already in place.

For the Workplace Communication Services procurement, Shared Services Canada is committed to engaging all stakeholders at the appropriate junctures in the procurement process, ensuring roles and responsibilities are clearly understood and agreed to, and seeking decision-maker commitment to ensure desired business outcomes are achieved.

Since the awarding of the Workplace Communication Services contract, Shared Services Canada put in place the Project Management Framework in 2017, which guides the effective management and delivery of the department’s projects throughout the project life cycle. The framework consists of tools such as a project control framework, integrated plans, risk registers, and the stakeholders responsibility and accountability matrix, which ensures continued alignment between all stakeholders to support the achievement of the desired business outcomes. The department’s Project Governance Framework documents and communicates the role of the various governance committees in providing effective oversight and a challenge function.

Shared Services Canada also has had a Procurement Governance Framework since July 2019, which was developed, implemented, and communicated, as appropriate, to provide procurement oversight, control, integration, risk management, and decision making for greater transparency and accountability. This framework tailors the required stakeholder oversight levels in relation to the size, scope, complexity, and risks of the procurements.

For the Next Generation Human Resources and Pay initiative, Shared Services Canada will continue to work with the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer at the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat as well as senior officials and users in other departments and agencies to define business needs and anticipate change management requirements. As the initiative moves from discovery to more substantive phases, decision makers will be required to be engaged thoroughly. A review of existing governance to align it with upcoming phases is underway.

Ensuring fairness and transparency in IT procurement

The monitoring of fairness, openness, and transparency in procurement needed improvement

1.54 We found that the detection and prevention of integrity risks in the procurement processes we looked at needed improvement. Public Services and Procurement Canada and Shared Services Canada made limited use of data analytics to identify procurement integrity issues, could not sufficiently show how they handled and resolved complaints about fairness, and did not ensure that the Fairness Monitoring Program supports the government’s commitment to promote fairness, openness, and transparency in the procurement process.

1.55 The analysis supporting this finding discusses the following topics:

- Limited use of data analytics to identify procurement integrity issues

- Incomplete tracking of fairness issues

- Insufficient information from third-party fairness monitors

1.56 This finding matters because the federal government has IT procurements underway that are worth billions of dollars. As the government and suppliers continue to apply agile procurement practices, there are more opportunities for real or perceived fairness issues to arise with the increased level of engagement to define requirements and potential solutions. The Government of Canada is committed to promoting fairness, openness, and transparency in procurement processes and, therefore, needs to protect against this risk.

1.57 It is important for contracting authorities to protect both the perceived and actual fairness of the collaboration process. The contracting authority is a person who represents the government in a given procurement. This person enters into a contract on behalf of Canada and manages the contract. The contracting authority is accountable for ensuring that procurements are conducted fairly, openly, and transparently.

1.58 Our recommendations in this area of examination appear at paragraphs 1.63, 1.64, and 1.68.

Limited use of data analytics to identify procurement integrity issues

1.59 We found that after our 2017 audit report on managing the risk of fraud, Public Services and Procurement Canada began developing its ability to detect some forms of wrongdoing, such as bid rigging and collusion. Using data analytics proactively for procurements can help identify procurement integrity issues to follow up on, such as indicators of potential fraud or fairness issues. In 2017, we recommended that the department conduct data analytics and data mining to identify signs of potential contract splitting, inappropriate contract amendments, and inappropriate sole-source contracting on a risk basis.

1.60 We observed that Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Fraud Detection and Intelligence Directorate had developed a procurement intelligence database to enable the aggregation, linking, and data mining of large volumes of procurement data from a variety of sources. The initiative was still in the early stages of development. At the end of our audit period, in August 2020, the directorate had just begun to document fraud risk scenarios and test its tools’ detection capabilities.

1.61 Public Services and Procurement Canada told us that its efforts to develop fraud detection tools for procurement were hampered by data quality issues. According to the department, the procurement information held by different branches and organizations is stored in different databases, in different formats, and without a common field or unique identifier to match data. This situation makes it difficult to analyze the available data efficiently. Public Services and Procurement Canada officials said that an electronic procurement solution that would solve most data quality issues was being built.

1.62 Similarly, we found that Shared Services Canada did not have a formal process to conduct data analytics or data mining or to identify red flags or anomalies in the procurement process. The department began to implement some quality assurance processes in 2019, but it did not have the ability to actively detect or monitor for procurement integrity issues.

1.63 Recommendation. Public Services and Procurement Canada should continue to advance its use of data analytics so that it can identify procurement integrity issues.

Public Services and Procurement Canada’s response. Agreed. Public Services and Procurement Canada will continue its implementation of using data analytics to identify potential procurement integrity issues by establishing a formal plan to operationalize data analytics and data mining by the end of the 2021–22 fiscal year.

1.64 Recommendation. Shared Services Canada should begin to use data analytics to improve its ability to identify procurement integrity issues.

Shared Services Canada’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada agrees that data analytics may contribute to enhance its ability to identify procurement integrity issues and will undertake experimentation to inform enhancements to its current practices. Shared Services Canada will augment its data analytics capabilities by developing a departmental analytics strategy and road map. Further, the department’s Data and Analytics Centre of Excellence will onboard procurement data into the department’s Enterprise Data Repository in 2021–22 and pilot the use of data science, artificial intelligence, and machine learning to improve the department’s ability to identify procurement integrity issues.

Incomplete tracking of fairness issues

1.65 We found that Public Services and Procurement Canada’s and Shared Services Canada’s contracting authorities did not keep complete records of potential procurement fairness issues and how they were resolved.

1.66 For example, we found that during the Benefits Delivery Modernization procurement, the contracting authority did not have any record of how it resolved an allegation of a potential conflict of interest involving a senior representative of a supplier who later became an Employment and Social Development Canada employee. Employment and Social Development Canada determined that the individual was not in conflict of interest. However, Public Services and Procurement Canada did not have any documentation in its records about how this allegation was resolved, how it was found not to affect the fairness of the process, or what actions might be needed to prevent potential future conflicts of interest.

1.67 For the Workplace Communication Services procurement, we found that Shared Services Canada’s contracting authority neither kept a complete record of how a potential fairness issue was resolved nor documented any conclusion about it. The department reissued an invitation to qualify multiple times without documenting why. It also cancelled the second invitation in favour of less stringent requirements even though 3 suppliers had already met the requirements of the second invitation. The contracting authority could not provide any documentation to support this decision.

1.68 Recommendation. Public Services and Procurement Canada and Shared Services Canada should improve their information management practices to help contracting authorities better demonstrate that procurement processes are fair. The departments should ensure that procurement records include, at minimum, file histories, explanations of problems that arise (and how they were resolved), and all relevant decisions and communications with implicated parties.

Public Services and Procurement Canada’s response. Agreed. Public Services and Procurement Canada is updating its information management procedures and best practices in terms of maintaining proper documentation related to its procurement files. Existing policies and procedures support a paper-based process, but with procurement moving to a paperless environment, work is underway to update policies and procedures to reflect the use of an electronic filing system. Further, tools and training on managing procurement files within the electronic filing system are also being developed. In addition to these efforts, the department is in the process of implementing the Electronic Procurement Solution, which will further improve the capture of procurement data and information associated with decision making. The department will implement the updated policies, procedures, tools, and training by the fourth quarter of the 2022–23 fiscal year. The phased implementation of the Electronic Procurement Solution is underway.

Shared Services Canada’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada is pleased to communicate that since the time of the audit, the department has implemented a number of information management tools and procedures to help demonstrate that procurement processes are fair. Shared Services Canada has developed guidelines on procurement file organization and makeup, a procurement file documentation list, and a compliance and quality assurance program, all of which help contribute to sound information management practices. The department will continue to communicate the importance of these practices to ensure that new and existing employees are aware of the tools and processes in place for sound information management.

Insufficient information from third-party fairness monitors

1.69 In agile procurement processes, the government works closely with suppliers, responding to their questions, holding one-on-one sessions, and reviewing their feedback on draft solicitation documents. As the government and suppliers increase their collaboration in complex IT procurements, there is a greater risk for real or perceived fairness issues to arise.

1.70 Public Services and Procurement Canada runs the Fairness Monitoring Program, which is intended to provide departments, government suppliers, Parliament, and Canadians with independent assurance that Public Services and Procurement Canada conducts its procurement activities fairly, openly, and transparently. The contracting authority is responsible for assessing whether to use the program according to the level of risk related to the sensitivity, materiality, or complexity of a procurement and submitting a request to the program. If a fairness monitor is warranted, the program engages a third-party contractor to observe all or part of the procurement activity in order to identify any fairness deficiencies. Involving a fairness monitor does not absolve the contracting authority of any responsibility for ensuring the fairness, openness, and transparency of procurement activities.

1.71 All 3 of the complex procurements we examined had assigned a fairness monitor. None of these fairness monitors identified a fairness deficiency during the course of our audit. However, we found that the contracting authority did not require nor obtain sufficient documentation from the fairness monitor on the activities observed, the monitor’s analysis, and the basis for the monitor’s conclusions. Without this information, contracting authorities may not have sufficient information to fulfill their responsibility for fairness, openness, and transparency of procurements.

1.72 Public Services and Procurement Canada told us that the Fairness Monitoring Program is not intended to operate as a control to detect and prevent procurement integrity risks; it is intended as a mitigating measure to support the contracting authority in addressing fairness issues when engaged. The department also told us that it will review the program to address identified gaps in fulfilling this role.

Conclusion

1.73 We concluded that Public Services and Procurement Canada, Shared Services Canada, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, and Employment and Social Development Canada made progress in planning and carrying out agile procurement processes for complex IT solutions that supported the achievement of business outcomes. However, the organizations did not provide sufficient guidance or training to staff and did not effectively engage stakeholders in their procurement initiatives.

1.74 We also concluded that improvements are needed to detect and prevent integrity risks in procurement processes. Public Services and Procurement Canada and Shared Services Canada should use data analytics to improve their ability to identify procurement integrity issues, improve their information management practices for tracking fairness issues, and ensure that contracting authorities obtain sufficient information from fairness monitors to support the government’s commitment to promote fairness, openness, and transparency in the procurement process.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the procurement of complex information technology solutions for the federal government. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs, and to conclude on whether Employment and Social Development Canada, Public Services and Procurement Canada, Shared Services Canada, and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Control 1 and, accordingly, maintains a comprehensive system of quality control, including documented policies and procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether selected organizations planned and carried out procurements for complex IT solutions that supported the achievement of business outcomes and the government’s commitment to promote fairness, openness, and transparency in the process.

Scope and approach

The audit focused on whether Employment and Social Development Canada, Public Services and Procurement Canada, Shared Services Canada, and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, in their respective roles, planned and carried out procurements that focused on business outcomes. We also consulted with National Defence on its experience with a procurement.

The audit took into account new approaches to procurement that are based on iterative learning. It also focused on whether systems are in place to detect and prevent procurement integrity risks and weaknesses prior to and during the procurement process.

For each of the 3 selected procurements, the audit team randomly sampled 22 supplier questions and comments and corresponding responses from documentation maintained by the contracting authority. The random samples were selected from the following populations:

- Next Generation Human Resources and Pay—669

- Benefits Delivery Modernization—884

- Workplace Communication Services—541

We obtained the supplier question-and-answer logs for each selected procurement as of March 2020. Responses to these supplier questions were prepared by the lead organization and contracting authority team for each initiative.

We did not examine contract administration activities or procurement activities carried out by individual organizations within their own contracting authority limits.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to determine whether selected organizations planned and carried out procurements for complex IT solutions that supported the achievement of business outcomes and the government’s commitment to fairness, openness, and transparency in the process:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, with Public Services and Procurement Canada and Shared Services Canada, documents and communicates direction to departments on how to simplify and modernize procurement processes. |

|

|

Departments accountable for selected procurements document clear business outcomes and establish clear accountabilities for outcomes. Public Services and Procurement Canada and Shared Services Canada have flexible procurement processes to enable business outcomes. |

|

|

Activities leading to a procurement and the procurement process involve clear and consistent communication with involved stakeholders and industry to promote fairness, openness, and transparency. |

|

|

Staff have the tools and training required to promote fairness, openness, and transparency throughout the procurement process. |

|

|

Systems are in place to detect and prevent procurement integrity risks and weaknesses prior to and during the procurement process. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 April 2018 to 31 August 2020. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 18 January 2021, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

Principal: Carol McCalla

Director: Joanna Murphy

Matthew Arnold

Glen Barber

Alycja Kinio

Jocelyn Matthews

Rebecca McNie

Stuart Smith

Zulfiqar Tarar

Faraz Tariq

Dung Thai

William Xu

List of Recommendations

The following table lists the recommendations and responses found in this report. The paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report, and the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the related discussion.

Modernizing IT procurement

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.47 To further support the government’s modernization of procurement,

|

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s response. Agreed. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat will continue to work with Public Services and Procurement Canada, Shared Services Canada, and other key stakeholders to develop, deliver, and promote formal and informal learning focused on agile procurement as well as develop and promote guidance and tools that support capacity building in the procurement community. Public Services and Procurement Canada’s response. Agreed. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Public Services and Procurement Canada, and Shared Services Canada are working closely together to successfully implement transformational IT procurements and fostering a common understanding of agile procurements. Work on agile procurement has been done in close partnership, in addition to engaging with other government departments that are procurement clients. Public Services and Procurement Canada will work in collaboration with the secretariat with respect to assessing the skills and competencies needed to support agile approaches to complex IT procurement. In addition, the department has a robust general procurement training regime in place for its procurement officers. The department has also undertaken significant efforts to further develop and launch guidance specific to agile procurement, as well as establishing a centre of expertise to support procurement officers in implementing this approach for public procurement. Guidance for procurement officers will continue to be refined and evolve, and as more procurements are undertaken using the agile procurement approach, opportunities will be identified to enhance training and other supporting tools. The department will complete this work by the fourth quarter of the 2022–23 fiscal year. Shared Services Canada’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada is working closely with the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat and Public Services and Procurement Canada with respect to undertaking transformational IT procurements and is fostering a common understanding of agile procurements. Work on agile procurement has been done in close partnership and through engagement with other government departments that are Shared Services Canada’s procurement clients. In December 2019, Shared Services Canada established the Centre of Expertise in Agile and Innovative Procurement, which is dedicated to supporting procurement officers in the implementation of agile and innovative procurements. The department has also undertaken significant efforts to launch and implement the Procurement Refresher and Essentials Program (PREP), which is continuously modernized. Shared Services Canada will continue to ensure that employees involved in transformational IT procurements have a more comprehensive understanding of agile and collaborative procurement methods through refinements to guidance, training, and support being provided to procurement officers. |

|

1.53 The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Employment and Social Development Canada, and Shared Services Canada should ensure that governance mechanisms are in place to engage senior representatives of concerned departments and agencies for each of the complex IT procurements we audited. This will be particularly important to support agile procurements of complex IT initiatives and their successful achievement of business outcomes. (1.48 to 1.52) |

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat’s response. Agreed. For the Next Generation Human Resources and Pay initiative, the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer in the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat will continue to work with Shared Services Canada and departments and agencies at senior levels as well as users from the human resource, pay, and manager communities to define business needs and anticipate change management requirements. As the initiative moves from discovery to more substantive phases, decision makers will be required to be engaged thoroughly. A review of existing governance to align it with upcoming phases is underway. Employment and Social Development Canada’s response. Agreed. At the time of the audit, the governance structure was in development in parallel with the remainder of the Benefits Delivery Modernization program but was not yet finalized. As of February 2021, there is a finalized and approved governance structure. The program has an effective stakeholder engagement mechanism with documented and communicated roles and responsibilities. The governance function is undergoing a refresh in preparation for Tranche 1 of the program. The revised structure adopts a holistic approach that integrates stakeholders through decision-making bodies, decision-making individuals, and bodies with advisory and assurance roles. Together, the participation of stakeholders across multiple forums ensures that the initiatives have the support they need to move forward and that business outcomes are met. Shared Services Canada’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada is pleased to report that processes are already in place. For the Workplace Communication Services procurement, Shared Services Canada is committed to engaging all stakeholders at the appropriate junctures in the procurement process, ensuring roles and responsibilities are clearly understood and agreed to, and seeking decision-maker commitment to ensure desired business outcomes are achieved. Since the awarding of the Workplace Communication Services contract, Shared Services Canada put in place the Project Management Framework in 2017, which guides the effective management and delivery of the department’s projects throughout the project life cycle. The framework consists of tools such as a project control framework, integrated plans, risk registers, and the stakeholders responsibility and accountability matrix, which ensures continued alignment between all stakeholders to support the achievement of the desired business outcomes. The department’s Project Governance Framework documents and communicates the role of the various governance committees in providing effective oversight and a challenge function. Shared Services Canada also has had a Procurement Governance Framework since July 2019, which was developed, implemented, and communicated, as appropriate, to provide procurement oversight, control, integration, risk management, and decision making for greater transparency and accountability. This framework tailors the required stakeholder oversight levels in relation to the size, scope, complexity, and risks of the procurements. For the Next Generation Human Resources and Pay initiative, Shared Services Canada will continue to work with the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer at the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat as well as senior officials and users in other departments and agencies to define business needs and anticipate change management requirements. As the initiative moves from discovery to more substantive phases, decision makers will be required to be engaged thoroughly. A review of existing governance to align it with upcoming phases is underway. |

Ensuring fairness and transparency in IT procurement

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

1.63 Public Services and Procurement Canada should continue to advance its use of data analytics so that it can identify procurement integrity issues. (1.59 to 1.62) |

Public Services and Procurement Canada’s response. Agreed. Public Services and Procurement Canada will continue its implementation of using data analytics to identify potential procurement integrity issues by establishing a formal plan to operationalize data analytics and data mining by the end of the 2021–22 fiscal year. |

|

1.64 Shared Services Canada should begin to use data analytics to improve its ability to identify procurement integrity issues. (1.59 to 1.62) |

Shared Services Canada’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada agrees that data analytics may contribute to enhance its ability to identify procurement integrity issues and will undertake experimentation to inform enhancements to its current practices. Shared Services Canada will augment its data analytics capabilities by developing a departmental analytics strategy and road map. Further, the department’s Data and Analytics Centre of Excellence will onboard procurement data into the department’s Enterprise Data Repository in 2021–22 and pilot the use of data science, artificial intelligence, and machine learning to improve the department’s ability to identify procurement integrity issues. |

|

1.68 Public Services and Procurement Canada and Shared Services Canada should improve their information management practices to help contracting authorities better demonstrate that procurement processes are fair. The departments should ensure that procurement records include, at minimum, file histories, explanations of problems that arise (and how they were resolved), and all relevant decisions and communications with implicated parties. (1.65 to 1.67) |

Public Services and Procurement Canada’s response. Agreed. Public Services and Procurement Canada is updating its information management procedures and best practices in terms of maintaining proper documentation related to its procurement files. Existing policies and procedures support a paper-based process, but with procurement moving to a paperless environment, work is underway to update policies and procedures to reflect the use of an electronic filing system. Further, tools and training on managing procurement files within the electronic filing system are also being developed. In addition to these efforts, the department is in the process of implementing the Electronic Procurement Solution, which will further improve the capture of procurement data and information associated with decision making. The department will implement the updated policies, procedures, tools, and training by the fourth quarter of the 2022–23 fiscal year. The phased implementation of the Electronic Procurement Solution is underway. Shared Services Canada’s response. Agreed. Shared Services Canada is pleased to communicate that since the time of the audit, the department has implemented a number of information management tools and procedures to help demonstrate that procurement processes are fair. Shared Services Canada has developed guidelines on procurement file organization and makeup, a procurement file documentation list, and a compliance and quality assurance program, all of which help contribute to sound information management practices. The department will continue to communicate the importance of these practices to ensure that new and existing employees are aware of the tools and processes in place for sound information management. |