2023 Reports 5 to 10 of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of CanadaReport 9—Monitoring Marine Fisheries Catch—Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Independent Auditor’s Report

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Findings and Recommendations

- Conclusion

- About the Audit

- Recommendations and Responses

- Exhibits:

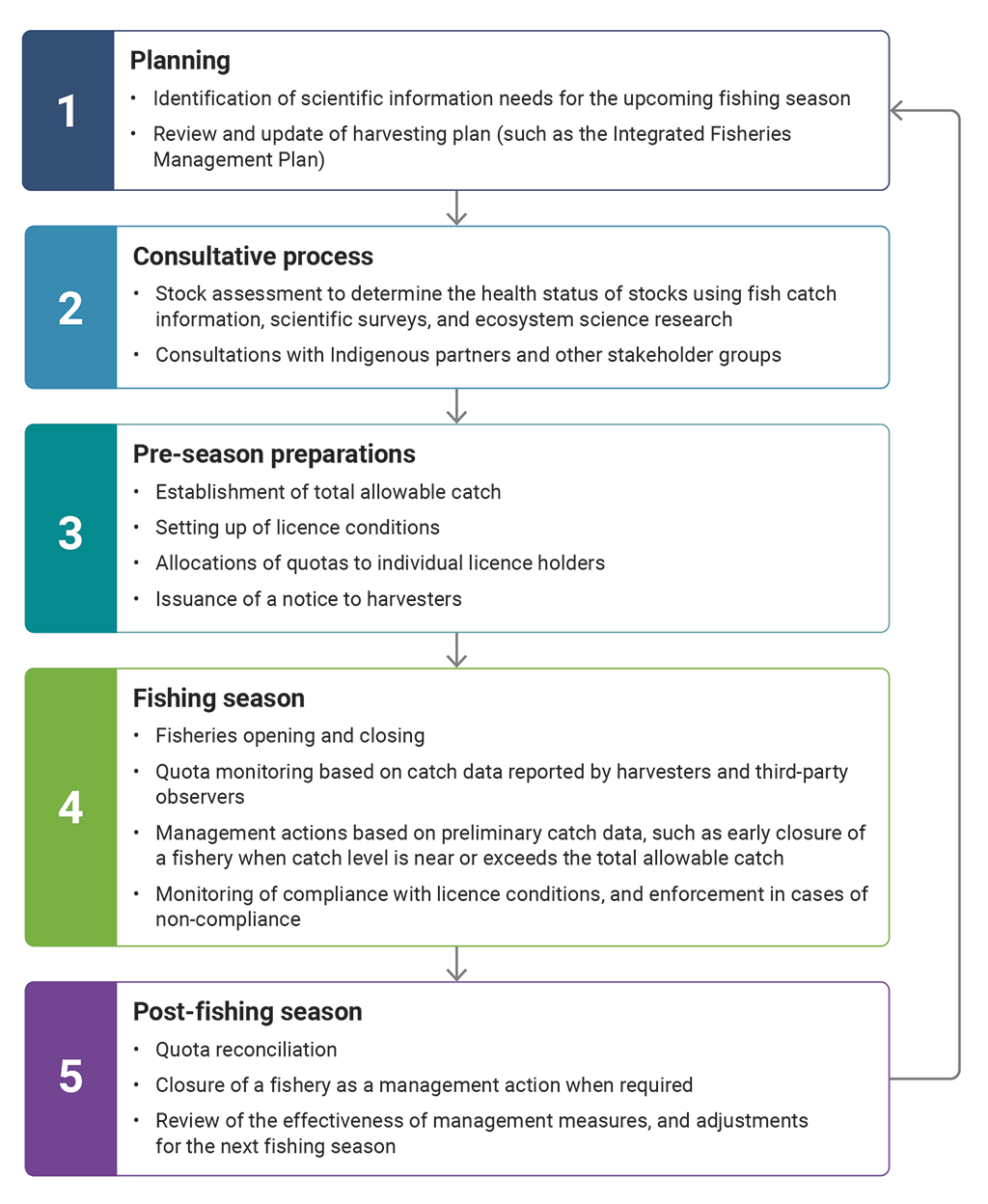

- 9.1—Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s annual cycle for fisheries management

- 9.2—As of December 2022, none of the fish stocks had undergone more than an assessment of current monitoring requirements

- 9.3—Coverage targets were not met in 2021 for many fish stocks subject to at‑sea observation

- 9.4—Coverage targets were not met in 2021 for many fish stocks subject to dockside monitoring

- 9.5—Timeliness requirements were not met in 2021 for many fish stocks subject to at‑sea observers

- 9.6—Timeliness requirements were not met in 2021 for many fish stocks subject to dockside monitoring

Introduction

Background

9.1 In Canada, approximately 72,000 people make their living directly from fishing and related activities. In 2021, the country’s commercial marine fisheries were valued at $4.6 billion. However, Canada’s marine ecosystems are under significant pressure from habitat loss and degradation, invasive species, pollution, climate change, and fishing.

9.2 Fisheries management has long been an issue in Canada. It is important to monitor fisheries catch to avoid repeating mistakes of the past. For example, until the later decades of the 20th century, Atlantic cod stocks were abundant off the east coast of Canada. The fish stocks were overexploited, and the Atlantic cod population collapsed. In 1992, the Government of Canada imposed a moratorium on cod fishing in the region. Since then, Atlantic cod stocks have not recovered. The collapse of the cod fishery had an impact that went far beyond environmental matters, causing the loss of thousands of jobs and creating social and cultural instability on Canada’s east coast.

9.3 Fisheries and Oceans Canada manages fisheries through an annual management cycle, which has 5 steps (Exhibit 9.1). The sustainable management of fisheries includes monitoring fisheries catch. Monitoring provides information that may include catch data, such as the quantity of the catch and bycatchDefinition 1 species and the biological characteristics (length, weight, or sex) of fish caught. This information can support management decisions, such as closing a fishery to avoid the depletion of fish stocks. The information also supports scientific assessments of fish stock health, as well as the setting of seasonal quotas to ensure the long‑term sustainable use of fish resources. Dependable, timely, and accessible data is necessary for these efforts to succeed. To be dependable, fish catch data must be of sufficient quality and stem from the implementation of monitoring programs and requirements that are adequate to support the achievement of fishery objectives. Fish catch data is also subject to departmental oversight, which includes ensuring that monitoring requirements are met, particularly in accordance with established coverage levels and timelines.

Exhibit 9.1—Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s annual cycle for fisheries management

Source: Based on information provided by Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Exhibit 9.1—text version

This chart shows the 5 steps of Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s annual cycle for fisheries management.

Step 1 is planning, which includes the following:

- Identification of scientific information needs for the upcoming fishing season

- Review and update of harvesting plan (such as the Integrated Fisheries Management Plan)

Step 2 is the consultative process, which includes the following:

- Stock assessment to determine the health status of stocks using fish catch information, scientific surveys, and ecosystem science research

- Consultations with Indigenous partners and other stakeholder groups

Step 3 is pre-season preparations, which include the following:

- Establishment of total allowable catch

- Setting up of licence conditions

- Allocations of quotas to individual licence holders

- Issuance of a notice to harvesters

Step 4 is the fishing season, which includes the following:

- Fisheries opening and closing

- Quota monitoring based on catch data reported by harvesters and third-party observers

- Management actions based on preliminary catch data, such as early closure of a fishery when catch level is near or exceeds the total allowable catch

- Monitoring of compliance with licence conditions, and enforcement in cases of non-compliance

Step 5 is the post-fishing season, which includes the following:

- Quota reconciliation

- Closure of a fishery as a management action when required

- Review of the effectiveness of management measures, and adjustments for the next fishing season

The next annual cycle begins with step 1 again.

9.4 Fisheries and Oceans Canada uses a variety of monitoring tools to collect data on catch and bycatch for a fishing season. These tools include fishing logbooks (paper or electronic records kept by harvesters of their fishing activities) and electronic devices (including cameras onboard vessels to validate catch data and fishing activities). Another monitoring tool is observation by the personnel of independent third-party companies, who verify catch data and also provide the department with information on biological characteristics. Third-party observers collect data on vessels at sea and when they are docked. For at‑sea observers and dockside monitoring, the department establishes coverage levels in consultation with the fishing industry—that is, it sets the percentage or the number of vessel trips for which observers must monitor fishing activities.

9.5 In 2013, the department implemented a multi-supplier model for fish catch monitoring and observation. Under this model, the department designates companies that are qualified to perform catch monitoring. The fishing industry and harvesters can choose among designated third-party observer companies and pay for their services. To obtain and maintain their designation, third-party observers are required to disclose and mitigate any conflicts of interest.

9.6 In September 2015, Canada adopted the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Monitoring fisheries catch is related to Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water) and more specifically to target 14.4:

By 2020, effectively regulate harvesting and end overfishing, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and destructive fishing practices and implement science-based management plans, in order to restore fish stocks in the shortest time feasible, at least to levels that can produce maximum sustainable yield as determined by their biological characteristics.

This international target has been incorporated into the 2022–26 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy as part of Canada’s commitment to conserving and protecting its oceans.

9.7 Fisheries and Oceans Canada is the federal government department responsible for ensuring that Canadian fisheries are sustainably managed. It is also responsible for ensuring that fisheries, oceans, and aquatic ecosystems are protected from unlawful exploitation and that Canada’s fisheries can continue to grow the economy and sustain coastal communities. Under the Fisheries Act, the department oversees commercial marine fisheries in Canadian waters in 6 administrative regions: Pacific, Arctic, Quebec, Gulf, Maritimes, and Newfoundland and Labrador. In addition, certain fisheries fall within the administrative division of the National Capital Region. As of 2022, there were 156 federally managed key commercial marine fish stocks in Canadian waters. These include fish stocks that have importance for economic, cultural, and ecosystem reasons or for their iconic value.

9.8 To manage the harvesting of key commercial marine fish stocks, the department annually establishes the total allowable catchDefinition 2 for most fisheries. This is a management tool for ensuring sustainable resource management, consistent with the objective of conserving the fish stocks. The department has other measures that it can deploy to control harvesting—for example, specifying the type and number of fishing gears and setting season opening and closing times for a particular stock. Under the Fisheries Act, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans may issue licences for fisheries. Under the Fishery (General) Regulations, the minister issues licences to harvesters, setting out conditions with which they must comply. The conditions may include the quota allotted to each harvester when applicable. They also include requirements for collecting catch data with the help of various monitoring tools and for reporting the data to Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

9.9 Under the Fisheries Act, the minister may require harvesters to keep records of fishing activities and submit the information to the minister in a specified form and by a specified date. The department uses the information in conducting research, creating a data bank, establishing objectives and codes of practice, or reporting on the state of fish, fisheries, or fish habitat.

9.10 The department is responsible for overseeing the performance of third-party observers. The responsibility includes monitoring the coverage, quality, and timeliness of data provided by the observers and conducting checks to ensure that observers comply with designation requirements.

Focus of the audit

9.11 This audit focused on whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada obtained dependable and timely fisheries catch monitoring information and whether the department used the information in support of its decisions to sustainably manage the harvesting of commercial marine fisheries.

9.12 This audit is important because monitoring catch is necessary to determine the quantity of fish harvested as well as bycatch, and their biological characteristics. Dependable and timely catch data is essential for evaluating whether actual harvesting is within the allowable catch limits that the department sets for each stock. Catch data is also important because it can inform scientific assessments of fish stock health, which help the department to set seasonal quotas that support the long‑term sustainable use of fish resources. Catch data is also essential to support effective management decisions, such as whether to close a fishery in order to avoid the depletion of fish populations.

9.13 More details about the audit objective, scope, approach, and criteria are in About the Audit at the end of this report.

Findings and Recommendations

Fisheries and Oceans Canada did not implement its policy for addressing known monitoring requirement issues

9.14 This finding matters because monitoring requirements are essential for the collection of dependable, timely, and accessible fish catch data from harvesters and third-party observers. Fisheries and Oceans Canada relies on this data to carry out core activities, such as managing fisheries sustainably, conducting fish stock assessments, and enforcing regulations and licence conditions.

9.15 To manage fish stocks, the department establishes monitoring requirements that will enable it to receive the dependable, timely, and accessible fish catch data that it needs. The department communicates the type of data it requires to harvesters and third-party observers. This includes

- the number and characteristics of the fish caught (such as the number of fish retained and thrown back, bycatch, biological data about fish caught, or the number of traps deployed on each fishing trip)

- tools used to gather data (for instance, logbooks, at‑sea and dockside monitoring, or onboard cameras)

- coverage percentages

- the timeliness of data received from third-party observers and harvesters

9.16 In our 2016 report on sustaining Canada’s major fish stocks, we found that the department did not have a clear rationale for determining the target coverage for at‑sea observers needed to provide information for managing fish stocks. In response to our recommendation, the department committed to finalizing a policy in 2017 that would introduce a risk‑based method to establish fishery monitoring coverage, ensure consistency across fisheries, and make reliable and timely data available for fisheries management.

Fishery Monitoring Policy not implemented

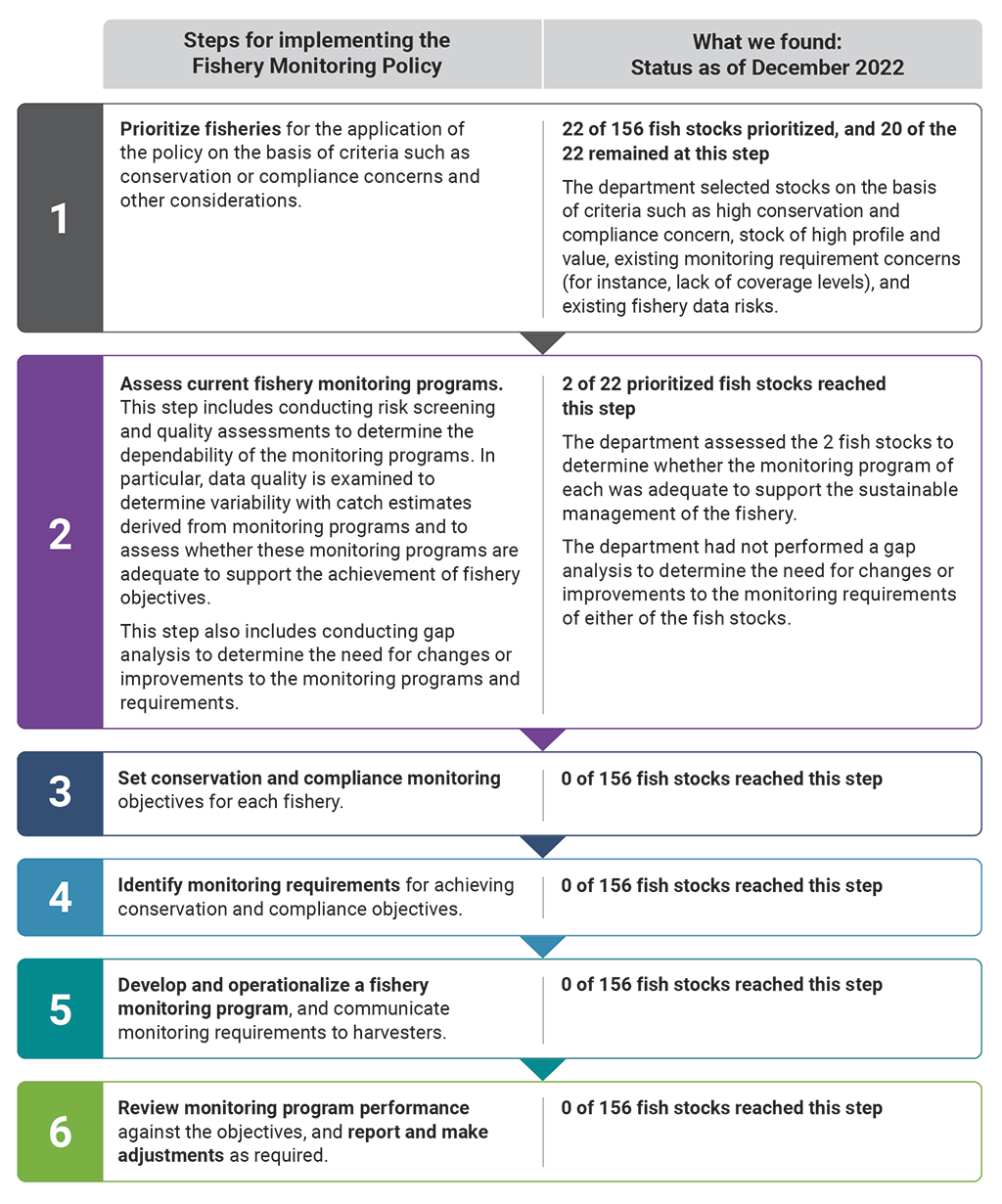

9.17 We found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada finalized and approved its Fishery Monitoring Policy in 2019. One of the policy’s primary objectives is to provide dependable, timely, and accessible data to support the sustainable management of fisheries. The policy sets out a framework for reviewing existing monitoring requirements to determine whether they are adequate or need to be updated. To implement the policy, the department developed a 6‑step process that involves, first, prioritizing which fish stocks are to be assessed for their monitoring requirements and then identifying areas for improvement, specifying new requirements, and communicating them to fish harvesters.

9.18 However, we found that from 2019 to 2022, the department prioritized only 22 of 156 key commercial marine fish stocks for the application of the policy, and it did not complete an assessment of monitoring requirements for any of these stocks (Exhibit 9.2). The result was that the department did not implement the policy for any fish stocks, and existing issues with data dependability and timeliness persisted.

Exhibit 9.2—As of December 2022, none of the fish stocks had undergone more than an assessment of current monitoring requirements

Source: Based on our analysis of information from Fisheries and Oceans Canada, including Introduction to the Procedural Steps for Implementing the Fishery Monitoring Policy, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 2019

Exhibit 9.2—text version

The following table shows the 6 steps for implementing Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s Fishing Monitoring Policy and the status that we found of each step as of December 2022.

| Step number | Steps for implementing the Fishery Monitoring Policy | What we found: Status as of December 2022 |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Prioritize fisheries for the application of the policy on the basis of criteria such as conservation or compliance concerns and other considerations. |

22 of 156 fish stocks prioritized, and 20 of the 22 remained at this step The department selected stocks on the basis of criteria such as high conservation and compliance concern, stock of high profile and value, existing monitoring requirement concerns (for instance, lack of coverage levels), and existing fishery data risks. |

|

2 |

Assess current fishery monitoring programs. This step includes conducting risk screening and quality assessments to determine the dependability of the monitoring programs. In particular, data quality is examined to determine variability with catch estimates derived from monitoring programs and to assess whether these monitoring programs are adequate to support the achievement of fishery objectives. This step also includes conducting gap analysis to determine the need for changes or improvements to the monitoring programs and requirements. |

2 of 22 prioritized fish stocks reached this step The department assessed the 2 fish stocks to determine whether the monitoring program of each was adequate to support the sustainable management of the fishery. The department had not performed a gap analysis to determine the need for changes or improvements to the monitoring requirements of either of the fish stocks. |

|

3 |

Set conservation and compliance monitoring objectives for each fishery. |

0 of 156 fish stocks reached this step |

|

4 |

Identify monitoring requirements for achieving conservation and compliance objectives. |

0 of 156 fish stocks reached this step |

|

5 |

Develop and operationalize a fishery monitoring program, and communicate monitoring requirements to harvesters. |

0 of 156 fish stocks reached this step |

|

6 |

Review monitoring program performance against the objectives, and report and make adjustments as required. |

0 of 156 fish stocks reached this step |

9.19 Before it developed the Fishery Monitoring Policy, the department acknowledged that it had never done a systemic review of its monitoring requirements. As a result, requirements varied for similar fisheries, and most fisheries lacked justification for their monitoring coverage levels—a situation that we found led to dependability problems, including timeliness issues.

9.20 The Fishery Monitoring Policy sets out a framework for consulting with stakeholders and Indigenous groups at various stages of implementation, starting with prioritizing fisheries for assessment. We found that as part of the prioritization work conducted to date, the department had not held any consultations with stakeholders and Indigenous groups, as called for in the policy.

9.21 The Fishery Monitoring Policy contains provisions for developing and implementing work plans and tracking progress. Despite this, we found that the department had not prepared an action plan or specified any concrete steps with timelines. The department also did not have any mechanism in place to track and evaluate progress.

9.22 In addition, we found that further to approving the policy in 2019, the department had not assessed the resources needed to implement it. This omission compromised the department’s ability to implement the policy. At the time, the department did not seek dedicated funding for implementation, nor did it reallocate funding internally for this purpose.

9.23 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should streamline the implementation of its Fishery Monitoring Policy by

- preparing and implementing an action plan, with clear steps and timelines for assessing gaps in monitoring requirements

- establishing new monitoring requirements where needed and operationalizing them

- monitoring the implementation of the policy, including examining whether the quality of catch data is adequate and scheduling regular reviews and adjustments

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

The department lagged on modernizing its fisheries information management systems

9.24 This finding matters because modernized data collection and information management systems across Canada would contribute to providing Fisheries and Oceans Canada with access to dependable and timely fishery monitoring data and would enable the department to make effective and timely decisions.

9.25 In our 2016 report on sustaining Canada’s major fish stocks, we found that the department’s 6 regions operated with regional and, in some cases, stock‑specific information systems for fisheries management. We also found that the systems did not communicate with each other. Because of the lack of system integration, this put the department at risk of not readily obtaining the quality data that it needed to make effective and timely decisions. We recommended that the department develop a system or systems that allow for data availability and comparison. In response, the department committed to implementing such a system by 2020.

9.26 Gaps in the department’s information management systems have been long‑standing. Its efforts to address these gaps focused on improving data quality and system integration so that decision makers would have access to dependable catch data when they needed it.

9.27 In 2003, the department introduced the concept of electronic logbooks to eventually replace paper logbooks for all commercial fisheries across Canada. Electronic logbooks allow harvesters to send catch data electronically to the department at the end of each fishing trip instead of mailing paper logbooks for eventual manual entry into the system. The intent was to address timeliness issues and provide more dependable data by reducing manual data entry errors.

Outdated information management systems

9.28 We found that Fisheries and Oceans Canada had not met its commitment to launch a new consolidated and integrated national information management system by 2020. Nevertheless, we found that in the 2015–16 to 2022–23 fiscal years, the department had spent around $31 million to improve its outdated information management systems.

9.29 In particular, we found that in 2021, the department had begun developing the Canadian Fisheries Information System that would provide ready access to catch data in order to support decision making. The department planned to implement the system first in the Newfoundland and Labrador region and then to introduce it gradually in other regions.

9.30 At the time of our audit, however, we found that the department had not completed key components of the Canadian Fisheries Information System that were related to our audit work. These included a quota management system, which was operationalized in 5 of the department’s 6 regions, and a catch monitoring and control system, which was still at an early stage of development in the Newfoundland and Labrador region. Overall, the objective of the department was to complete the national integration of the Canadian Fisheries Information System by the 2029–30 fiscal year, a decade later than the original target date.

9.31 As a result of the absence of an integrated Canada‑wide system, the department still faced issues related to the lack of system integration and the lack of ready access to dependable and timely catch data.

9.32 In 2014, in an effort to improve data collection by commercial harvesters, the department began work on the National Electronic Logbook initiative. In 2020, an internal briefing note stressed the need to improve data collection and indicated that electronic logbooks would be mandatory by 2023. At the time of our audit, we found that the department was still assessing its options for the design of electronic logbooks. It was also considering extending the use of paper logbooks beyond 2024 while allowing for the voluntary use of electronic logbooks. The department planned to eventually incorporate electronic logbooks into the Canadian Fisheries Information System because eliminating manual entries would improve the accuracy and timeliness of catch data.

9.33 To address long‑standing issues, Fisheries and Oceans Canada should expedite the implementation of an integrated national fisheries information system that would allow the department to

- provide timely access to catch data to inform the management of fisheries, including compliance with harvesting and licence conditions

- contribute to ensuring the quality of fisheries monitoring information

- make fisheries monitoring information available to support other departmental objectives, such as science and enforcement

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

The department did not ensure that catch data collected by third-party observers was dependable and timely

9.34 This finding matters because the oversight of third-party fisheries observer companies is supposed to give Fisheries and Oceans Canada access to dependable and timely catch and bycatch data and enable the department to ensure that there is sufficient monitoring coverage for the management of fisheries. Catch data is essential to support timely management decisions, particularly in cases where the total amount of fish caught exceeds the limits established for sustainable harvesting.

9.35 Fisheries and Oceans Canada relies on third-party observer companies to verify catch and bycatch data provided by harvesters and to deliver on their monitoring responsibilities. Their role is to provide accurate, timely, and independent verification of harvesting activities. The department has 2 programs in place for third-party observers:

- The dockside monitoring program provides independent third-party verification of fish landings. The observers record harvest data, including the weight and species landed. Dockside monitoring is the primary and, in some areas, the only source of landing data.

- The at‑sea observer program places designated private-sector observers aboard fishing vessels. Their tasks include monitoring fishing activities, monitoring bycatch, collecting biological samples, and reporting suspected non‑compliance with fishing regulations and licence conditions.

9.36 To obtain and maintain their designation, third-party observers must meet certain requirements, such as

- disclosing conflicts of interest with fishing entities subject to monitoring, explaining how such conflicts will be resolved, and ultimately resolving them

- delivering monitoring of fish landing and other data collection in a timely manner

9.37 The department sets out and communicates to third-party observers monitoring requirements, associated coverage levels, and time frames for observers to submit the data they collect. For the 2021 fishing season, the department determined that 118 out of 156 fish stocks were subject to verification by third-party observers. If third-party observers were not available, the department relied on catch data recorded by harvesters in their logbooks.

9.38 The department also needs to ensure that third-party observers carry out their responsibilities in a consistent manner. For this purpose, the department is responsible for, among other things, overseeing the performance of third-party observers by monitoring the coverage and timeliness of the data they provide.

9.39 During the fishing season, the department receives preliminary catch data from harvesters. After the season ends for a fishery, the department compiles the fish catch monitoring data provided to it and establishes the total amount of fish caught for each fishery. For fisheries for which quotas are allotted to harvesters, when the department finds that harvesting exceeded the total allowable catch for a stock, it conducts a quota reconciliation—that is, it deducts the overrun amount from the following season’s harvesting allowance for the fish stock and adjusts the individual quotas allocated to harvesters in the form of fishing licences.

No improvement in oversight of third-party observers

9.40 In our 2016 report on sustaining Canada’s major fish stocks, we recommended that the department improve its oversight of third-party fisheries observer programs in order to ensure the sufficient coverage of fishing vessels, timely data, and the mitigation of potential or actual conflicts of interest on the part of observer companies.

9.41 The department committed to acting on our recommendation. In particular, the department indicated that it would

- develop and implement an interim protocol for mitigating conflicts of interest within third-party observer programs

- verify compliance with third-party observer program requirements

- revise the third-party observer programs

- develop a fishery monitoring policy

We found that the department had not made satisfactory progress on addressing our 2016 recommendation.

9.42 In 2016, the department committed to developing and implementing an interim protocol for mitigating conflicts of interest within the at‑sea observer and dockside monitoring programs. The department indicated that the protocol would remain in force until the revision of the third-party observer programs (see paragraph 9.49).

9.43 We found that the department finalized the interim protocol in 2017. The protocol describes steps that third-party observer companies and the department must follow to mitigate declared conflicts of interest, such as family or business ties between observers and fish harvesters. Among other things, the interim protocol requires the department to maintain a national list of declared conflicts of interest and the associated mitigation measures. It also requires the department to monitor the implementation of the mitigation measures and take follow‑up action in cases of non‑compliance.

9.44 We found that the interim protocol had not been fully implemented at the time of our audit. Of the 5 regions with third-party observer programs, 1 did not maintain its own list of conflict‑of‑interest issues and 1 did not receive any declared conflicts of interest. The other 3 each maintained a list and had recorded conflict‑of‑interest issues involving more than 100 observers. Two of the 3 regions maintaining a list did not take further action on cases in which the mitigation measures were not implemented. One region maintained a list of declared conflicts but indicated that it had conducted no monitoring to assess whether mitigation measures for declared conflicts were implemented. Lastly, the department did not maintain a national list as required.

9.45 Without the full implementation of the interim protocol, the department faced increased risk of relying on inaccurate catch and bycatch data to support management decision making.

9.46 In response to our 2016 recommendation, the department also committed to implementing a program to verify whether third-party observer companies were complying with the department’s third-party observer program requirements.

9.47 The department developed a methodology for verifying whether third-party observer companies complied with the requirements of the observer programs. A national headquarters unit conducted the verifications. However, we found that the methodology was not suitable to address our past audit finding and recommendation on implementing systematic controls to ensure the sufficient coverage of fishing vessels and to ensure data quality and timeliness. In particular, there were no standardized procedures to verify whether observer companies complied with requirements regarding the timely submission of catch data. In addition, the unit assessed data quality by interviewing regional officials instead of assessing and documenting the accuracy of information.

9.48 During the period of our audit, only 9 of 21 observer companies underwent verifications, which together covered only 16 fisheries. All 9 companies were found to have at least 1 issue related to the lack of the disclosure of conflicts of interest and associated mitigation measures, to the insufficient coverage of fishing vessels, or to the failure to report accurate and timely catch data. The results led the unit in charge of the verifications to make 16 recommendations to regional departmental coordinators, calling for improved oversight of third-party observer companies to ensure that they address the issues found in the verifications. However, of the 16 recommendations, we found that 9 were not implemented. These concerned improving departmental oversight of data quality control and coverage requirements.

9.49 The department also committed to reviewing its separate programs for dockside and at‑sea third-party observers and integrating them into a single improved program. The improvements that the department envisaged for the new program included graduated measures and time frames to manage non‑compliance issues, such as problems with data quality and timeliness.

9.50 The department planned to finalize the new program in 2018. However, we found that it was not finalized by the time of our audit. The department attributed the delay to internal pressures and to the coronavirus disease (COVID‑19)Definition 3 pandemic. It had not set a new timeline for finalizing and implementing the program. The delay limited the department’s ability to take corrective measures aimed at ensuring the dependability and timeliness of monitoring.

9.51 As mentioned in paragraph 9.17, in 2019, the department finalized its new Fishery Monitoring Policy, which focuses on improving monitoring requirements to provide dependable, timely, and accessible fishery data and communicating the new requirements to third-party observers for their implementation. However, we found that 4 years later, the department had not made any significant progress in implementing the policy.

9.52 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should complete its review of third-party observer programs to incorporate measures with associated time frames to manage non‑compliance issues, such as the lack of the disclosure of conflicts of interest and associated mitigation strategies, the insufficient coverage of fishing vessels, and the lack of quality and timely data.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Gaps in meeting coverage and timeliness requirements for third-party observers

9.53 We found that the department had not formalized any standard procedures for consistently tracking the coverage and timeliness of catch data received from third-party observers. This is particularly important because the department relies heavily on third-party observers to collect dependable catch data.

9.54 In the absence of a departmental process for systematically tracking whether third-party observers fulfilled their monitoring responsibilities, we asked the department to indicate whether, on the basis of internal records, the coverage levels and timeliness requirements were met and to provide supporting evidence.

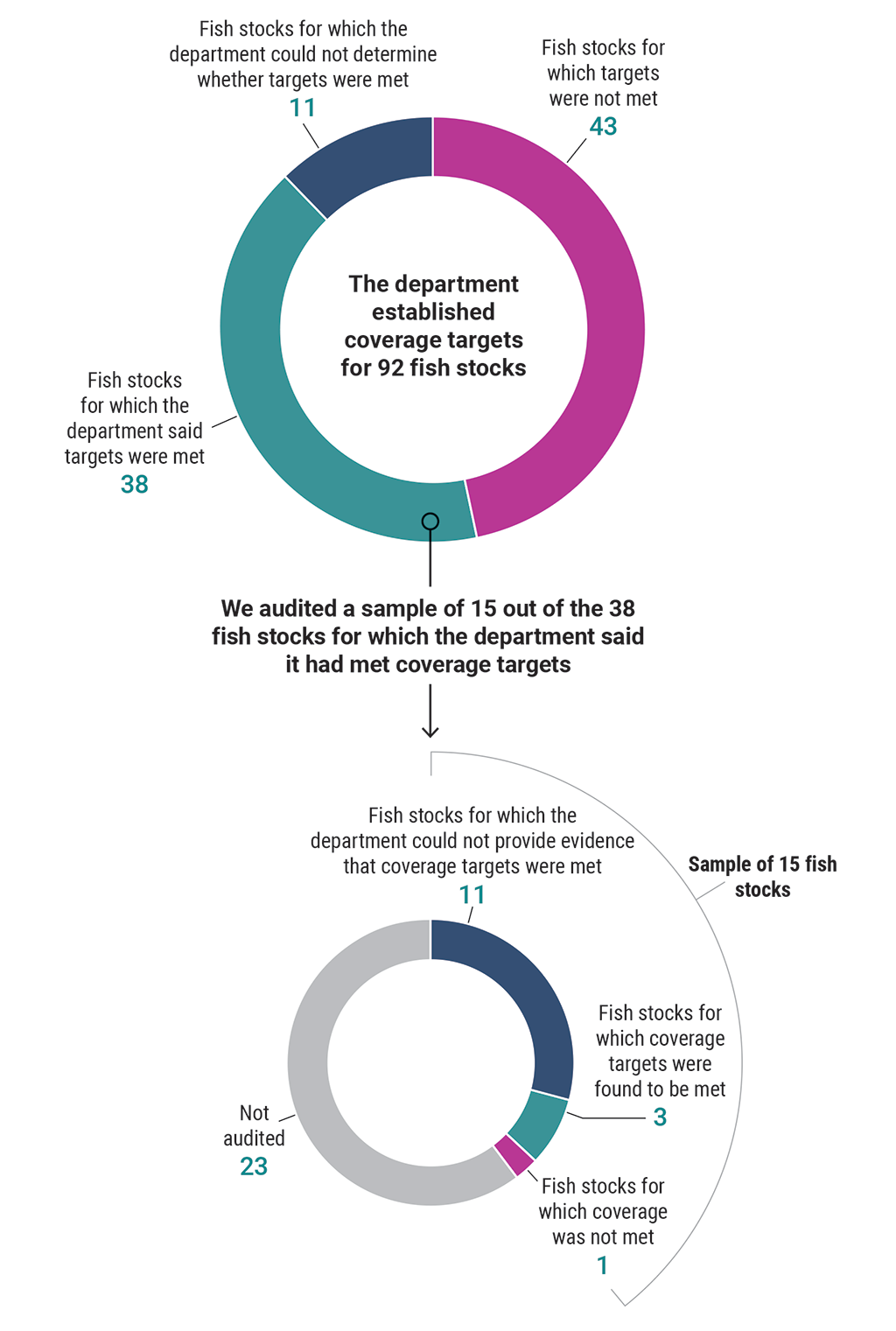

9.55 We found coverage problems for the fish stocks that this requirement applies to. Of the 101 fish stocks subject to at‑sea observation, Fisheries and Oceans Canada indicated that it had not established coverage targets for 9 fish stocks, but it had established coverage targets for 92 fish stocks. Among the fish stocks for which coverage targets were established, the department indicated that the targets were not met for 43 fish stocks, and in many cases, the department could not tell whether the established target was met (Exhibit 9.3). In cases where the department indicated that the established coverage targets were met, we audited a sample to verify accuracy and found that in most cases, the department could not provide evidence to support its statements. This amounted to problems with at‑sea observation coverage for 75 fish stocks.

Exhibit 9.3—Coverage targets were not met in 2021 for many fish stocks subject to at‑sea observation

Source: Based on our analysis of information from Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Exhibit 9.3—text version

This chart shows to what extent coverage targets were met in 2021 for fish stocks subject to at‑sea observation.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada established coverage targets for 92 fish stocks. Of these 92 fish stocks, there were 43 for which targets were not met, there were 38 for which the department said targets were met, and there were 11 for which the department could not determine whether targets were met.

We audited a sample of 15 out of the 38 fish stocks for which the department said it had met coverage targets. Of the sample of 15 stocks, there were 11 for which the department could not provide evidence that coverage targets were met, there were 3 for which coverage targets were found to be met, and there was 1 for which coverage was not met. The remaining 23 out of the 38 fish stocks were not audited.

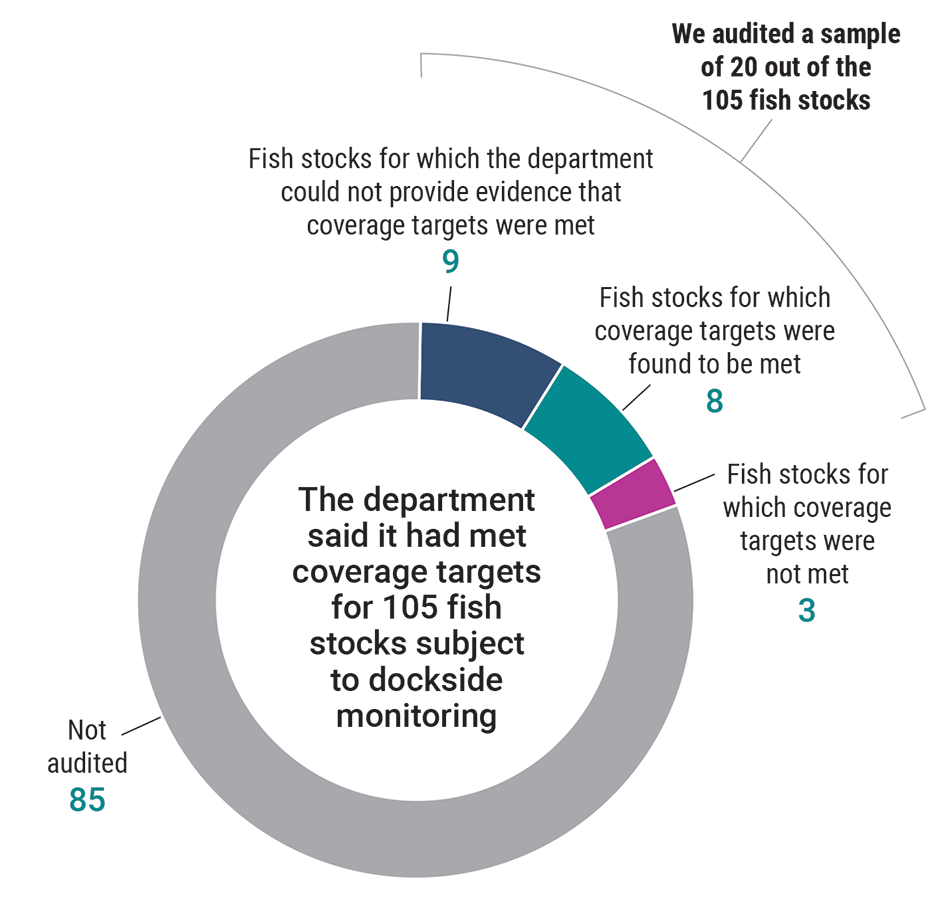

9.56 Of the 106 fish stocks subject to dockside monitoring, Fisheries and Oceans Canada indicated that the established coverage targets had been met for 105 fish stocks (Exhibit 9.4). However, when auditing a sample of these fish stocks to verify accuracy, we found that in most cases, either the department could not provide evidence to support its statements or the department showed that the coverage target was actually not met. In total, we found problems with dockside monitoring coverage for 13 fish stocks.

Exhibit 9.4—Coverage targets were not met in 2021 for many fish stocks subject to dockside monitoring

Source: Based on our analysis of information from Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Exhibit 9.4—text version

This chart shows to what extent coverage targets were met in 2021 for fish stocks subject to dockside monitoring.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada said it had met coverage targets for 105 fish stocks subject to dockside monitoring.

We audited a sample of 20 out of the 105 fish stocks. Of the sample of 20 stocks, there were 9 for which the department could not provide evidence that coverage targets were met, there were 8 for which coverage targets were found to be met, and there were 3 for which coverage targets were not met. The remaining 85 out of the 105 fish stocks were not audited.

9.57 In our opinion, the department did not meet the objective of its multi-supplier model for fish catch monitoring and observation. According to the department, staff shortages meant that companies providing third-party at‑sea observation services were experiencing challenges in meeting required coverage levels. In addition, these companies faced difficulties covering the associated costs, which became the responsibility of the fishing industry as of 2013. At the time of our audit, the department was reviewing options for addressing this situation, including video monitoring.

9.58 In addition, the department has a responsibility for communicating to observers the timelines for submitting catch data, which is then used to inform management decisions. We found timeliness problems regarding the submission of data.

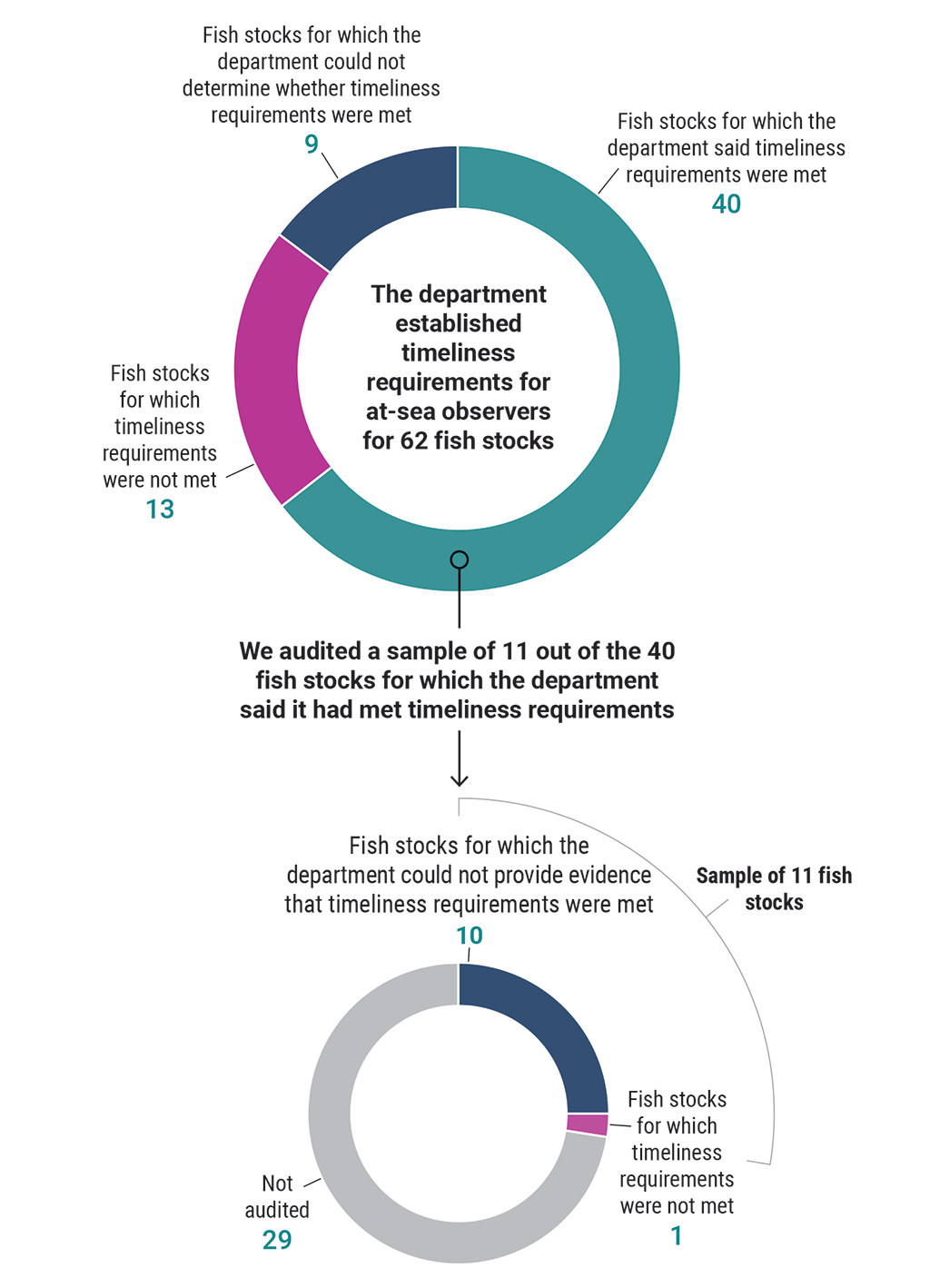

9.59 Of the 101 fish stocks subject to at‑sea observation, Fisheries and Oceans Canada indicated that it had not established timeliness requirements for 39 fish stocks, but it had established timeliness requirements for 62 fish stocks (Exhibit 9.5). In many cases where the department established timeliness requirements, it either indicated that the requirements were actually not met or did not know whether timelines were met. For the remaining fish stocks for which the department indicated that the established timeliness requirements were met, we audited a sample to verify accuracy and consistently found that either the department was not in a position to provide evidence to support its statements or based on evidence provided, the timeliness requirement was actually not met. This amounted to problems with the timeliness requirements for 72 fish stocks subject to at‑sea monitoring.

Exhibit 9.5—Timeliness requirements were not met in 2021 for many fish stocks subject to at‑sea observers

Source: Based on our analysis of information from Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Exhibit 9.5—text version

This chart shows to what extent timeliness requirements were met in 2021 for fish stocks subject to at‑sea observers.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada established timeliness requirements for at‑sea observers for 62 fish stocks. Of these 62 fish stocks, there were 40 for which the department said timeliness requirements were met, there were 13 for which timeliness requirements were not met, and there were 9 for which the department could not determine whether timeliness requirements were met.

We audited a sample of 11 out of the 40 fish stocks for which the department said it had met timeliness requirements. Of the sample of 11 stocks, there were 10 for which the department could not provide evidence that timeliness requirements were met, and there was 1 for which timeliness requirements were not met. The remaining 29 out of the 40 fish stocks were not audited.

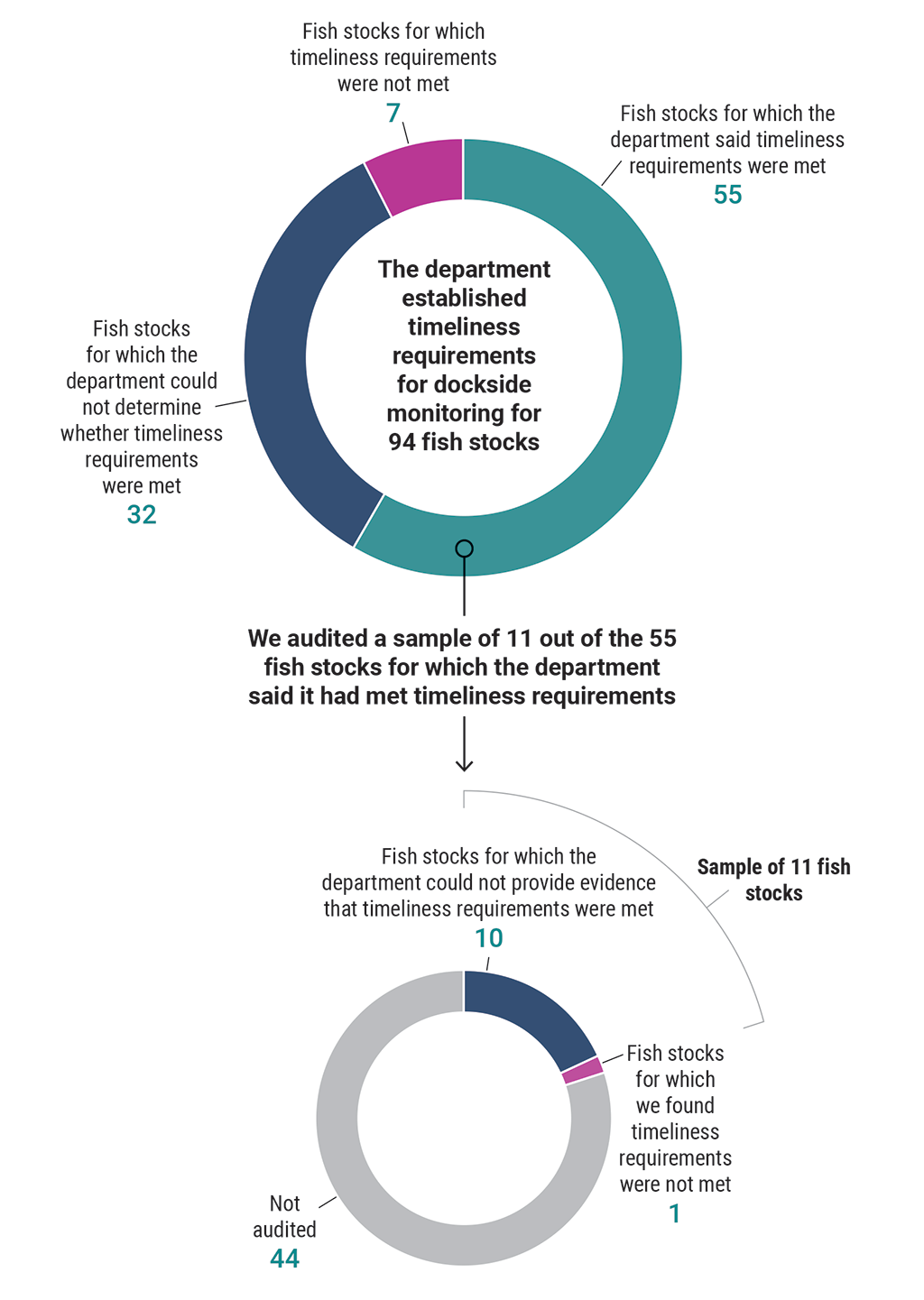

9.60 Of the 106 fish stocks subject to dockside monitoring, Fisheries and Oceans Canada indicated that it had not established timeliness requirements for 12 fish stocks, but it had established timeliness requirements for 94 fish stocks (Exhibit 9.6). After compiling departmental input and auditing a sample of the fish stocks for which timeliness requirements were established to verify accuracy, we found a total of 62 fish stocks for which timeliness requirements either were not established in the first place by the department, were not supported by evidence that data was delivered as required by the third party, or were not actually met.

Exhibit 9.6—Timeliness requirements were not met in 2021 for many fish stocks subject to dockside monitoring

Source: Based on our analysis of information from Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Exhibit 9.6—text version

This chart shows to what extent timeliness requirements were met in 2021 for fish stocks subject to dockside monitoring.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada established timeliness requirements for dockside monitoring for 94 fish stocks. Of these 94 fish stocks, there were 55 for which the department said timeliness requirements were met, there were 32 for which the department could not determine whether timeliness requirements were met, and there were 7 for which timeliness requirements were not met.

We audited a sample of 11 out of the 55 fish stocks for which the department said it had met timeliness requirements. Of the sample of 11 stocks, there were 10 for which the department could not provide evidence that timeliness requirements were met, and there was 1 for which we found timeliness requirements were not met. The remaining 44 out of the 55 fish stocks were not audited.

9.61 As a result of weaknesses in obtaining and tracking third-party observer monitoring information, in particular to ensure that coverage and timeliness objectives were met, we found that the fish catch information was to a large extent not dependable.

9.62 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should develop and implement a nationally consistent procedure for systematically tracking whether third-party observers deliver fisheries catch monitoring information as required, in terms of coverage, timeliness, and data quality.

The department’s response. Agreed.

See Recommendations and Responses at the end of this report for detailed responses.

Fisheries catch information used to support management decisions on the sustainable harvesting of fisheries

9.63 After the end of the 2020 and 2021 fishing seasons, the department compiled catch data and compared it against the total allowable amounts. On the basis of data for these 2 seasons, the amount of fish caught was within established limits for 122 of 130 fish stocks for which a total allowable catch had been established and for which no management measures were required. In 8 cases, however, we found that catch data indicated that the stocks were harvested above the total allowable catch limit. For those 8 stocks, the department applied its processes as intended and took a management decision for sustainable harvesting: It deducted the overrun amount from the following season’s total allowable catch, or it closed the fishery.

9.64 In the context of reporting progress toward the achievement of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water) and more specifically its target 14.4, the department publicly reported that 1 commercial marine fish stock did not meet the performance indicator for that target—that is, the percentage of the major fish stocks that are harvested at sustainable levels. This information appeared in the department’s 2021–22 Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy Report.

9.65 We found that the department used available fish catch data to support decisions to sustainably manage the harvesting of commercial marine fisheries. However, given that the department did not ensure that this data was dependable and timely, in our opinion, it did not form a solid basis that the department could rely on for decision making.

Conclusion

9.66 We concluded that Fisheries and Oceans Canada had not obtained dependable and timely fisheries catch monitoring information, but used this information to support its decisions to sustainably manage the harvesting of commercial marine fisheries.

9.67 Our 2016 audit found problems with data dependability and timeliness, which the department committed to addressing by implementing a series of measures. However, the department had not made any significant progress, and the problems persisted. The department had not established dependable and timely fisheries catch monitoring requirements and had not operationalized them for delivery as required by its Fishery Monitoring Policy. The department also had not improved its oversight of third-party observers, as it had committed to do, to enable access to dependable and timely fisheries catch information. It had not improved its oversight both in terms of mitigating conflicts of interest to make sure they can trust information provided and in terms of tracking whether the data provided by third-party observers was dependable, was timely, and met coverage objectives. In addition, the department had not met its commitment to modernize its information management systems.

9.68 Fisheries and Oceans Canada used available fisheries catch monitoring data to inform management decisions on the sustainable harvesting of commercial marine fisheries. However, given that the department had not ensured that this data was dependable and timely, in our opinion, it did not form a solid basis that the department could rely on for decision making.

About the Audit

This independent assurance report was prepared by the Office of the Auditor General of Canada on the monitoring and use of catch data for commercial marine fisheries. Our responsibility was to provide objective information, advice, and assurance to assist Parliament in its scrutiny of the government’s management of resources and programs and to conclude on whether the monitoring of marine fisheries catch complied in all significant respects with the applicable criteria.

All work in this audit was performed to a reasonable level of assurance in accordance with the Canadian Standard on Assurance Engagements (CSAE) 3001—Direct Engagements, set out by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada) in the CPA Canada Handbook—Assurance.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada applies the Canadian Standard on Quality Management 1—Quality Management for Firms That Perform Audits or Reviews of Financial Statements, or Other Assurance or Related Services Engagements. This standard requires our office to design, implement, and operate a system of quality management, including policies or procedures regarding compliance with ethical requirements, professional standards, and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

In conducting the audit work, we complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the relevant rules of professional conduct applicable to the practice of public accounting in Canada, which are founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, and professional behaviour.

In accordance with our regular audit process, we obtained the following from entity management:

- confirmation of management’s responsibility for the subject under audit

- acknowledgement of the suitability of the criteria used in the audit

- confirmation that all known information that has been requested, or that could affect the findings or audit conclusion, has been provided

- confirmation that the audit report is factually accurate

Audit objective

The objective of this audit was to determine whether Fisheries and Oceans Canada obtained dependable and timely fisheries catch monitoring information and whether the department used the information in support of its decisions to sustainably manage the harvesting of commercial marine fisheries.

Scope and approach

The audit focused on Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s activities related to the collection and use of fisheries catch monitoring information for the 156 key commercial marine fish stocks identified by the department in 2021. We examined

- the establishment of fisheries catch monitoring requirements and their operationalization

- the oversight of third-party fisheries observers to determine whether the department had access to reliable catch and bycatch data enabling it to track marine fish stocks catch

- the implementation of the department’s plans to support the modernization of catch data collection and information management systems

- the department’s use of fisheries catch monitoring information to inform management decisions in support of the sustainable harvesting of commercial marine fisheries

We did not examine the monitoring of individual quotas allotted from the total allowable catch to harvesters in the form of fishing licences or the enforcement of quotas for fish stocks that did not have a total allowable catch established. Instead, we focused on aggregated fishery-level management and decision making in cases where the total allowable catch limit was exceeded for the 2020 and 2021 fishing seasons for quota-based fisheries.

We gathered audit evidence through document reviews, interviews with federal officials, questionnaires completed by fisheries managers for the key fish stocks, on‑site visits, and data analysis.

When auditing the oversight by Fisheries and Oceans Canada of third-party observers, we examined whether coverage and timeliness requirements were met to determine whether monitoring programs in place for the key commercial marine fish stocks were fully delivered. We also examined whether the key departmental controls in place to ensure the quality of data were implemented. However, we did not assess the quality of the data itself. We also did not assess whether the risk screening and quality assessment tools were suitable to determine dependability of catch data. In conducting audit work on coverage and timeliness requirements, we asked the department to indicate whether these requirements were met, and we noted deficiencies. In cases where the department stated that the requirements were met, we took a representative sample of fish stocks to verify accuracy with supporting evidence. In most cases, the department could not provide evidence supporting its response, and accuracy could not be confirmed. Hence, the results of these verifications could not be extrapolated to all the cases where the department stated that the requirements were met. We therefore reported only on the fish stocks indicated as problematic by the department in addition to those additional cases found as problematic as a result of auditing sampled fish stocks.

When auditing management decisions on the sustainable harvesting of commercial marine fisheries (that is, the management of quotas), the audit focused on aggregated fishery-level management and decision making in cases where the total allowable catch limit was exceeded for the 2020 and 2021 fishing seasons for quota-based fisheries. We did not examine the allocation by Fisheries and Oceans Canada of individual quotas to harvesters from the total allowable catch nor whether this information was accurately reflected in resulting fishing licences. Also, we did not examine the fishery management of quotas by the department in cases where fish stocks that did not have a total allowable catch established.

We did not examine the enforcement activities conducted by the department’s fishery officers, unless these activities were directly related to the monitoring of fisheries catch data gathered by third-party fisheries observers and harvesters in the course of commercial marine fishing activities. Also excluded from the scope of the audit were the recreational, freshwater, and Indigenous fisheries because they were not subject to the departmental activities being audited. Also, this audit did not examine scientific activities conducted by the department to determine the health status of fish stocks.

This audit examined relevant United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and targets and the targets in the Canadian Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals. The audit also considered the availability of reliable, disaggregated data for measuring progress toward these goals and targets.

Criteria

We used the following criteria to conclude against our audit objective:

| Criteria | Sources |

|---|---|

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada has established fisheries catch monitoring requirements and operationalizes them pursuant to its Fishery Monitoring Policy. |

|

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada has improved its oversight of third-party fisheries observers to enable access to dependable and timely catch data, and to sufficient monitoring coverage. |

|

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada has implemented its plans to support the modernization of fisheries catch data collection and information management systems. |

|

|

Fisheries and Oceans Canada used available fisheries catch monitoring information to inform management decisions on the sustainable harvesting of commercial marine fisheries. |

|

Period covered by the audit

The audit covered the period from 1 November 2019 to 31 December 2022. This is the period to which the audit conclusion applies. However, to gain a more complete understanding of the subject matter of the audit, we also examined certain matters that preceded the start date of this period.

Date of the report

We obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence on which to base our conclusion on 16 October 2023, in Ottawa, Canada.

Audit team

This audit was completed by a multidisciplinary team from across the Office of the Auditor General of Canada led by David Normand, Principal. The principal has overall responsibility for audit quality, including conducting the audit in accordance with professional standards, applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and the office’s policies and system of quality management.

Recommendations and Responses

In the following table, the paragraph number preceding the recommendation indicates the location of the recommendation in the report.

| Recommendation | Response |

|---|---|

|

9.23 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should streamline the implementation of its Fishery Monitoring Policy by

|

The department’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada recognizes the need to accelerate work on implementing the Fishery Monitoring Policy. The federal government invested $30.9 million over 5 years with $5.1 million ongoing from 2023–2024 to 2028–2029. The department is working on implementation. This is the first time this policy has received dedicated funding to advance implementation. Given the amount of funding, the department prioritized a set of stocks upon which to implement the policy in order to maximize the benefits of this funding—focusing, for example, on major fish stocks described in regulations made under section 6.3 of the Fisheries Act as currently known to be suffering from data issues, as key forage species and thus keystones in the ecosystem, and so on. The department will work to advance the implementation of the policy to increase the ability of fisheries to produce reliable, timely, and accessible catch information that can be used to inform stock assessments and effectively implement management measures. Implementation date: Ongoing. Implementation of the Fishery Monitoring Policy on prioritized stocks will be the initial phase of the department’s approach over the next 5 years starting in 2023–2024. Prioritized stocks are scheduled to complete policy implementation by 2028–2029, with further stocks to follow in the future. |

|

9.33 To address long‑standing issues, Fisheries and Oceans Canada should expedite the implementation of an integrated national fisheries information system that would allow the department to

|

The department’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada refocused project efforts onto licensing, quota, catch, and effort business lines in the fall of 2021. The initiative’s (Canadian Fisheries Information System) more targeted and achievable objective is to consolidate and modernize siloed legacy regional licensing systems, as well as to implement electronic logbooks so harvesters are submitting their data directly to the department replacing paper forms. There have been additional key corrective actions in response to lessons learned from a third-party review in 2019–2020. These include the following:

A new accelerated implementation plan for the Canadian Fisheries Information System is currently being considered. If implemented, the plan will deliver more information technology capabilities sooner to better support commercial fisheries monitoring. Implementation date: The implementation timeline is 2024–2027. |

|

9.52 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should complete its review of third-party observer programs to incorporate measures with associated time frames to manage non‑compliance issues, such as the lack of the disclosure of conflicts of interest and associated mitigation strategies, the insufficient coverage of fishing vessels, and the lack of quality and timely data. |

The department’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will undertake the following:

Full implementation date: 2026 |

|

9.62 Fisheries and Oceans Canada should develop and implement a nationally consistent procedure for systematically tracking whether third-party observers deliver fisheries catch monitoring information as required, in terms of coverage, timeliness, and data quality. |

The department’s response. Agreed. Fisheries and Oceans Canada will undertake the following:

Implementation date: 2026 |